FRC716 – Darley Fulks – Kentucky Wild Horse

by John Harrod, September 2015

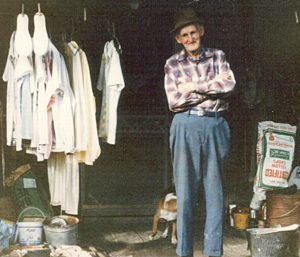

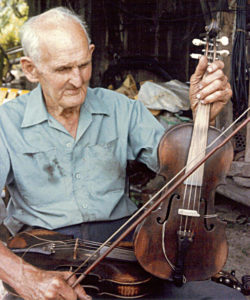

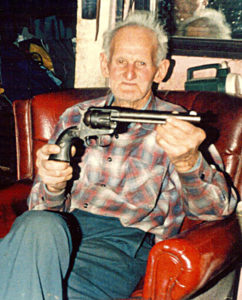

Darley Fulks (1895-1990) in his long life worked as an oil driller, traveling both north and south from his native Wolfe Co., Kentucky, meeting other musicians, and learning tunes everywhere he went. But the greatest portion of his repertoire came from the older generation in his own county. Many of his tunes came from his grandfather and some he could trace to his great-grandfather. Consequently, his music represents both an exceptionally old collection of tunes, many pre-dating the Civil War and unique to him, and an exceptionally diverse range of styles and genres. A search of Kuntz’s Fiddler’s Companion along with requests to knowledgeable fiddle scholar friends yielded only a few analogs and possible sources. In fact, as more and more such collections from regional repertoires come to light, from the samples preserved by fiddlers like Darley Fulks, who were not known outside their own communities and who were overlooked by the collectors and performers who have defined the modern fiddle repertoire, we realize how vast is the corpus of traditional American fiddle music.

To listen to Darley talk about all the fiddlers he remembered from his travels and from growing up in Wolfe Co. – fiddlers we will never hear who also played many tunes Darley did not remember but probably would have eventually if he had been granted a few more years on this earth – is to be reminded of something Gus and I often talked about as we sought out the old fiddlers in Kentucky: what we don’t know far outweighs what we do. We can only wonder about the tunes that were played, the individuals who played them, and the individual styles that were not discovered and documented. But Darley’s music, so different from much of what we heard and yet pointing in so many different directions, sheds some light into the unknown. Perhaps his importance is in his singularity, his unique sense of timing, his individuality that lies beyond the borders of any presumed style. For all we know this may have been the profile of the backwoods fiddlers of the 19th century.

The keys indicated for the tunes describe the finger patterns, not the pitch. Darley, like most fiddlers of his generation, always tuned a step and a half or two full steps below modern 440 pitch.

- Manassas (C) – My grandfather played it. I had an uncle that played it. A lot of people played it, but they learned it from old Dave Athea. I’m satisfied that “Manassas” come in here from Virginia with old Dave Athea.

This piece is a good introduction to Darley’s style – the bouncy, syncopated saw strokes, string crossings, bluesy slides, and dramatic pauses that hover on the edge of a phrase, building up tension before going on. Meeting Darley for the first time in 1976 and then hearing Doc Roberts soon thereafter forever changed my notions of what old-time fiddling was all about. It seemed that here was the source of a stream of fiddling that had its own language and history and diverged sharply from everything else I was hearing at the time. As I followed those sounds through the years I came to believe that most all of the fiddlers I heard in Kentucky preserved some of that timing and some of that bowing that made them sound different and led some people to talk of a “Kentucky style.”

- Rocky Shoals (G) – It’s an old time piece. I heard my grandfather play it, my uncle, and Bill Day. He’s got it. This is the piece that J. W. Day called “The Nigger’s Wedding.”

- Everybody’s Favorite (C) – Dave Athea was an old barber there in town (Campton), it was just a little village then, maybe one store, a post office, just a few houses. John, that’s been 75 years. Well, that old man was a fiddling fool. He charged a boy a dime for cutting his hair and a man a quarter, that’s the truth. He cut my hair for a dime, John, and when he wasn’t cutting hair or shaving somebody, he’d be a-playing the fiddle and I used to sit on the store steps there in his barber shop and listen at him play. And I never did forget that piece. And after I got older my grandfather played it, and I had an uncle that played it, a lot of people played it. But he was the man that brought it in here. He was from Virginia, he come in here from Virginia.

Darley called this piece a two-step. It was played in neighboring Estill and Clark Counties as a fiddle and banjo tune in the key of D but their low part was not as elaborate as Darley’s setting in C. Another “Everybody’s Favorite” played by George Lee Hawkins further north in Bath Co. was a ragtime tune and not related to either of these.

-

- Old Folks Schottische (F) – Darley could get more out of a schottische than any fiddler I ever heard. Although he learned a number of them when he was drilling for oil in Michigan, he said this one came from Dave Athea.

- Groundhog (G) – This variant of the usual melody of this tune shows Darley’s bowing to good effect. This is what I regard as the basic bowing style of central and northeastern Kentucky: bouncy saw strokes and string crossings mimicking the sound of dancing feet. Kerry Blech hears a bluesy inflection in this piece reminiscent of the African-American fiddler from Georgia, Andrew Baxter.

- President Garfield’s Favorite (F) – John, I was working up in Illinois and there was an awful fiddler up there, an awful fiddler. And he was playing some pieces for me and I was playing some pieces for him that he’d never heard and I’d never heard these pieces. Well, one night he played a piece and I said “What do you call that piece?” and he said “It’s ‘President Garfield’s Favorite.” And he said there’s a feller over here that’s got President Garfield’s violin but it’s ruined. And he said there’s a history with it, he has that too.

“Awful” of course has an older meaning as Darley’s generation used it. It means literally inspiring awe or astonishment. There were two other tunes widely played in Kentucky that commemorated the fiddling president – “Garfield’s Blackberry Blossom,” and “Garfield’s Funeral March” – but this waltz seems to be unique to Darley and occurs nowhere else that I can find.

- Nero the Slave (C) – I tell you what I think, John, where it came from. I think that some soldier that survived the Civil War brought that back here from the South.

It is interesting that a black fiddler named Nero appears in the lyrics to “The Grand Old Jubilee” (track 43), another tune that Darley believes was brought to Wolfe Co. by a soldier returning from the Civil War.

-

Martha Campbell (D) – There was two colored fellers in Mt. Sterling. I took a pair of mules down there and give ’em away, swapped them for an old horse. It was a young crazy thing, didn’t have no sense. Now John, that was in 1915 or 16. Well, they played “Martha Campbell,” and I’d never heard it before. That’s a bluegrass tune, no doubt about that. It’s not a mountain tune. Well, they beat all I ever heard in my life, and I’ll bet you they made a hundred dollars that day playing the fiddle and guitar. I don’t even know their names. But anybody could go to Mt. Sterling and find out who they were from them old timers there. They played all day only they took time to go – the town was wet – they’d go get beer or whatever they wanted. John, they’d play and they’d be a-playing and they’d both stop like that. And then they’d start again. They had played together so much that that feller on that guitar knew the very minute that fiddle would stop, and he’d stop. And then they’d start again. Stop and start music I called it. Well, I was horseback and I had fifty mile to ride and I lived over here at Bethel. Do you know where Bethel is? I lived over in there. And I never got home til after daylight, and I hummed that piece all the way home so I wouldn’t forget it. And another one they played was “Paddy on the Turnpike” but I thought more of “Martha Campbell” because it had more music in it. I couldn’t hold them both and I held on to that one. Now that coarse part, they don’t play that no more, but them colored folks, they played it. That’s the way they played it. If they played it wrong, they played it wrong fifty years ago.

Martha Campbell (D) – There was two colored fellers in Mt. Sterling. I took a pair of mules down there and give ’em away, swapped them for an old horse. It was a young crazy thing, didn’t have no sense. Now John, that was in 1915 or 16. Well, they played “Martha Campbell,” and I’d never heard it before. That’s a bluegrass tune, no doubt about that. It’s not a mountain tune. Well, they beat all I ever heard in my life, and I’ll bet you they made a hundred dollars that day playing the fiddle and guitar. I don’t even know their names. But anybody could go to Mt. Sterling and find out who they were from them old timers there. They played all day only they took time to go – the town was wet – they’d go get beer or whatever they wanted. John, they’d play and they’d be a-playing and they’d both stop like that. And then they’d start again. They had played together so much that that feller on that guitar knew the very minute that fiddle would stop, and he’d stop. And then they’d start again. Stop and start music I called it. Well, I was horseback and I had fifty mile to ride and I lived over here at Bethel. Do you know where Bethel is? I lived over in there. And I never got home til after daylight, and I hummed that piece all the way home so I wouldn’t forget it. And another one they played was “Paddy on the Turnpike” but I thought more of “Martha Campbell” because it had more music in it. I couldn’t hold them both and I held on to that one. Now that coarse part, they don’t play that no more, but them colored folks, they played it. That’s the way they played it. If they played it wrong, they played it wrong fifty years ago.

It’s interesting that Darley makes a distinction here between bluegrass tunes (tunes he believed were native to the bluegrass region of the state) and mountain tunes. “Martha Campbell” was considered the “national anthem” by Kentucky fiddlers who boasted that no one but a Kentucky fiddler could play it. Although it was most prevalent in the bluegrass region of central Kentucky, it was also played in the mountains (J. W. Day, Monroe Gevedon, John Salyer, James Crase, Walter McNew, Stanley Fowler, Buddy Thomas, and Bob Prater). Darley’s account of hearing it for the first time is some evidence for its African-American origins, as if the style and rhythm of the tune were not enough to identify it.

-

Story of Farewell Kentucky – Anyway John, years ago this music teacher and this professor come here – his wife was a music teacher. I had a cousin, she was a lot older than I was. I played a lot with her, a lot on the fiddle and her on the piano. And this cousin of mine was one of her students, you know. But she played this for her and told her the story of it. Well, somebody had told her about this old lady being at this place, I think it was Bardstown, when Stephen Foster left Kentucky. He was supposed to make a speech the next day. Well, instead of making that speech, they heard him late at night on the piano. They didn’t know what they thought – maybe he was practicing, they thought maybe he was going to sing a song the next day. Well the next day instead of making a speech, he sung this song. And that music teacher learned it to Nora Horton and she learned it to me. And when he got ready to leave, this old lady that told this professor‘s wife, she told him, she says “Stephen, I’d like to have that music to that and the words to that song,” and he sent it to her. Well it was never spread through the country like other songs he made, like “Old Kentucky Home,” “Home Sweet Home,” “Swannee River.“ Probably nobody else in the whole country knows that song. I got the music with no ballad. And it’s bad, you know, people neglect things like that. And I’m satisfied that I’m the only living person – unless it’s locked up in an old wore-out trunk somewhere – that knows that tune.

John: What are the words you know?

Darley: “In this great land I stand with my hat in my hand where the grass is as blue as the sky. It is no surprise that I have tears in my eyes as I’m here to bid you goodbye.“ And that’s all I know.

John: What was it called, what was the name of it?

Darley: “Farewell Kentucky“ is what Nora Horton called it. From Stephen Foster.

Kerry Blech found a song, “Farewell Kentucky Home” by George B. Gookins, published in 1895, and pointed out that Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home” spawned a lot of imitations, so who knows what the true origin of Darley’s tune might have been. It is at least possible that his third-hand account of the story is true and it does represent a lost Stephan Foster tune.

- Farewell Kentucky (F)

- Cumberland Gap (G) – “I went down to Cumberland Gap, see my granny and my great grandpap.”

“Cumberland Gap” was a standard tune in east Kentucky and always played in G. The general preference of Kentucky fiddlers for the key of G may be due to the fact that the layout of the scale on the fingerboard is ideally suited for the bowing and phrasing tendencies that they preferred.

- Atlanta Hornpipe (C) – This tune is not related to the “Atlanta Hornpipe” in Ryan’s Mammoth Collection of 1883. I did not record Darley’s source for it, but it may be one of the tunes that came into Wolfe Co. with a soldier after the Civil War. See his comments on “Nero the Slave” (track 7) and “The Grand Old Jubilee” (track 43).

- Kentucky Wild Horse (G) – They was a fellow up there (in Michigan) from Tennessee – I went several times to this dance – and he played our kind of music, an old fellow from Carter County. I’ll never forget that old guy. Him and his son-in-law, he was from Carter County over here– I forget his name – and he says, “I hear you’re from Kentucky.” I was up there one night and this boy at the home where we was playing, this boy worked with me, he was a tool dresser, and he knew this old man, he was his neighbor. And he come down to the hotel where I stayed and I’d go up there and we’d play. He says, “They tell me you’re from Kentucky” and they was having a dance there that night. I said, “Yeah, I’m from Kentucky,” and he said “What part?” and I told him. He says “I’ve heard of that country, but I was never over in Wolfe County.” Well, he was from Carter County and he’d been up there for 10 or 12 years and he was getting gray and he had a white mustache. Well, he was a-bragging and a-going on and we was drinking homebrew, a bunch of it. He said, “I play 500 pieces,” and I said, “You do? You must be an awful fiddler.” He said “Well, I was give up to be the best in that part of the state of Kentucky,” and he kept on. Well, when they started dancing, why he said “You go ahead and play,” and I said “No, you play, you go ahead. You’re used to this music, you go ahead and play it.” Well the very minute he laid his hand on the fiddle, I swear he couldn’t play. Then this boy that worked with me, it was his father’s house, and he wanted us to play. Finally he says, “ Well now, boys, you fellows can take over.” So we played “Kentucky Wild Horse.” Well, after we got that settled, he said, “You can’t get ahead of a Kentuckian, can you?” Poor old fellow wouldn’t play another lick.

- The Old Richmond Waltz (F) – The drama that Darley instilled into his playing of waltzes captures the sound of the light classical music of the late 19th century which was finding its way into the repertoire of some of the more skilled players. This was another piece that he learned from Dave Athea.

- Chat – The Old Richmond Waltz

- Ol’ Massa’s Horn (C) – “Hurry up children, I hear Ol’ Massa’s horn.” I heard my grandfather play that one many, many times, and he learned it from his father. Old Bill Day played it too.

The sound effects imitating the horn occupy another of those pauses that Darley incorporated into most of his tunes. The breadth and variety of so-called crooked tunes – the many different ways they can depart from standard 32-bar phrasing – is as varied as the individual fiddlers themselves. Darley often put these pauses in the middle of a phrase, not at the end, withholding the resolution of the phrase, which had the effect of creating tension and anticipation. Nikos Pappas, who has studied these permutations and attempted to classify them, probably has a name for Darley’s preferred approach. Whatever else we might say about it, it is one of the defining traits of his style.

- Down South Rag (C) – learned from a barber in Muskegan, Michigan. “He was a southerner from down south someplace. That’s the first time I ever heard it.”

Kerry Blech cites Wilbur Sweatman’s 1911 composition “Down Home Rag” as the likely source of the tune the barber played in Michigan. He says that Ohio fiddler Lonnie Seymour also played it. Darley’s piece departs somewhat from the 1911 composition in typically Darley fashion so it might be regarded as a distinct variant.

- Grinnell’s Schottische (C) – I learnt that in Michigan from a girl that played an accordion and her dad played a fiddle in a hotel where I stayed. I stayed there a year.

- Fontaine’s Ferry (G) – That’s a Kentucky piece I learned over in Western Kentucky -Fontaine’s Ferry. An old man ran a ferry there on the Green River – it’s been there for years and years unless they’ve built a bridge – the Green River, just before you get into Owensboro. The old ferry’s there, I crossed it. When I worked in Alabama and come back to Owensboro, you cross that ferry. Fontaine’s Ferry is the name of it. Billy Sauceman is bound to have made it. Now I’ll tell you what they told me down there. I never met the man but he lived way accrost over there somewhere. He lived right there close – we was 14 miles south of Owensboro. And he lived up in that country someplace there. And he would go down the river on the steamboat and play on the steamboat and that’s the way he made a living. And they said one night they was having a fiddle contest and there was some fiddlers told Billy if he wouldn’t play that piece, they’d play against him. But he won it anyhow, he won it on another piece. They was afraid of that piece. Now it’s a real fiddle piece, there’s no doubt about that.

This tune may have come from western Kentucky but it has all the hallmarks of Darley’s style, suggesting that he, like most fiddlers of his generation, came up with his settings by putting them through the filter of his own imagination. This intense individuality which can totally transform the source a fiddler learned from may run counter to the local style and should remind us of the difficulty in attempting to define and generalize about regional styles (although I do it all the time, a habit I acquired from the giddy times I spent on the road with Gus and Mark, full of excitement and wonder at the amazing sounds we were hearing and trying to put it all into some kind of context.)

- After the Ball (C) – Composed by Charles K. Harris and published in 1892. A cylinder recording of it came out in 1894, it first appeared on 78 in 1924 on Paramount, and the next year it became a hit with Vernon Dalhart’s recording on Columbia. (Kerry Blech) This was one of Darley’s favorite tunes. He had deep feeling for those old sentimental pieces as he called them. and he made them come alive for me.

- Newt Williams’ Piece (C) –

John: Did you play at the picture show down at Campton?

Darley: Yeah, yeah. If I wasn’t out on a well somewhere and I was in town, why they’d always let me know and they’d always get after me to play the fiddle down there and bring the band, I’d bring these boys that played with me down there and play for the picture show. Yeah, old Newt Williams, he’s dead now, Newt Williams. Every time he’d holler out, “Play my piece, Darley,” and I knew who it was a-hollering and I’d always play him that piece.

This is another piece that seems to have roots in the ragtime era, or possibly in something prior to that out of which ragtime grew.

- Cackling Hen (G) – Kerry cites Gus Meade: the earliest publication was in Emma Bell Miles’ Spirit of the Mountains (1905). It was first recorded by Fiddlin’ John Carson in 1923. Mabel called this “her piece.” It was very popular among Kentucky fiddlers, another G tune that gives free reign for a lot of good bowing and sound effects.

- All I Got’s Done Gone (C) – “All I Got’s Done Gone” is the best fiddle piece I ever heard in my life. Doc Roberts made that piece. Somebody ought to go and string a little bunch of roses along on top of his grave for that piece. Now John, that’s one piece I heard one time and I caught it – from Silas Rogers. That’s a good piece. He come up, he had a sister that, let’s see, how was that? The hotel man’s youngest sister married Silas Rogers. He run a big hotel in Campton. And that’s the first time I ever met him, there. And he come up here, him and George and maybe another one or two, his band, and norated around they’s gonna have music in the courthouse. Well, the courthouse was crowded. Or maybe he come up on Friday, I don’t remember when he come, but he put up over there at that hotel. Well, that night I went out there. I met him and we got down in the dining room and they played and played and played and played. Played, I guess ’till midnight. And he played that piece and I caught that piece that night.

There was an old man at the filling station and I played that piece and he just went crazy over it. And I told him who made it, Fiddling Doc Roberts made it, but he didn’t believe me. He thought it was from some other country or it come in here from somewhere.

Actually Doc Roberts himself credited African-American fiddler Owen Walker (born in 1854) as his source for the piece. It must have been widespread before Roberts’ time because it was widely played by older fiddlers throughout the bluegrass, including many who had never heard of Doc Roberts.

- The Irish Pub (C) – I learned that up in Michigan. It’s a jig. But they dance them jigs up there. They don’t dance like we do.

This was the only true jig that Darley played. It is significant that he learned it in his travels up north. Jigs were practically non-existent in Kentucky south of the Ohio River.

- Leather Britches (G) – Neil Gow’s publication of “Lord MacDonald’s Reel” in 1792 seems to be the earliest appearance of this American standard. Kentuckian William Houchens made the first recording of “Leather Britches” for Gennett in 1923. (Kerry Blech) The tune has all but died out with the passing of Darley’s generation, but it was still played by all the old fiddlers I recorded in the 1970s and 80s.

- Shady Lane (F) – I’ve heard my grandfather play that piece. There was a colored girl there that he raised and she used to dance that. If anybody would come, John, company, you know, they wanted Fan to dance, my grandfather would play the fiddle and she’d dance that piece. All them old fiddlers played it. It’s a two-step.

Darley’s love of playing in F, even breakdowns that might seem to fit as well in G, reveal interesting bowing and finger patterns that will grow on you with time. He liked the way the scale laid out and in those tunes he used the full scale. All the old fiddlers played in F, he would say. To get that in another key, why you’d have to go all the way to the bridge.

- Muskegan Schottische (C) – The name identifies the source. Named after the city in Michigan, he learned it during the time he spent there as an oil driller. This schottische bears a close resemblance to the commonly played “Rustic Dance,” which is often the only schottische a southern fiddler might know.

- Cindy (G) – A standard fiddle and banjo tune in the East Kentucky mountains, this is one of a number of tunes that the older fiddlers played in G that shifted somewhere along the way to the key of A (others being “Cripple Creek,” “Sally Gooden,” “Sourwood Mountain,” and “Ida Red”). It’s worth noting that Darley played no tunes in the key of A and did not play in cross tuning. The key of G for this tune lends itself to the kind of bowing that Kentucky fiddlers preferred (referenced above in the notes to #5 Groundhog and #12 Cumberland Gap).

- Little Black Dog (G) – Darley remembered the words:

Little black dog come a-trottin’ down the road

with his tail hanging down like a handle on a gourd

We observe that this tune is basically the same as John Salyer’s “Jack Wilson” with the difference being that Salyer’s tune is in the key of D.

- The Forked Deer (C) – John, that’s “The Forked Deer.” They play it different now, don’t they? That’s the way they played it when I was a kid. That’s the way it was played, I’ve heard it too many times. I heard my grandfather play it. As Kerry points out, the tune was published in Knauff’s Virginia Reels (1839) and recorded early by Eck Robertson (1922) and Am Stuart (1924) though Darley’s unique setting in the key of C was derived as he says from local sources.

- Andrew Jackson (G) – The old the folks all played it. My granddaddy, my uncle all played it. It’s an old one, it’s really an old piece. Now that fellow up in Paintsville playing “Andrew Jackson,” and I said, “What do you call that?” The town was wet there and that was our headquarters where the contractor lived that we worked for. And there was a park there and there was a beer joint there and them musicians would get in there on Saturday in that park. You could see some of the best fiddlers you ever saw and then you’d see some about the worst. Banjo players and guitar players and some of them had bands, you know. Well, the park would be full of these fellows on Saturdays. And I come along there, I was coming home that way, and there was an old man, an old man by the name of Bob Johnson. I watched him for, I guess, hours. Hummed every piece he played and he was a fiddling fool, an old man. Well, I tell you, it was a circus, you know. Well, I come to a fellow, he was playing, he was a-playing “Andrew Jackson.” I said, “What do you call that piece?” He said, “Whoa, Pretty Woman.” Well, I said, “That’s not right.” I didn’t want to get into a racket with him, you know. He said, “That’s what I always heard it called.” I said, “That’s not right.” I’d heard old Bob Johnson play that tune. I said, “Come out here, I want to show you that you’ve been misinformed.” I said, “That’s not the name of that piece.” He said, “What’s the name of it?” I said, “’Andrew Jackson’ is the name of it.” So we went out there and old Bob was about half drunk. He’d quit and I said “Bob” – I think I gave him a quarter – I said, “Will you play ‘Andrew Jackson’ for me?” “Yeah.” And I said, “What’d I tell you?” See, he’d heard somebody that didn’t know the name of that piece, heard some old fiddler play it and called it, “Whoa, Pretty Woman.” That’s bad, you know. They leave out, they leave out so many parts of them. “Whoa, Pretty Woman.” Poor old Bob a-sitting there humming everything he played. I never saw nothing like it in my life. I guess he’s dead now.

This is Darley’s version of the tune otherwise known in Kentucky as “Waynesboro.” The title suggests that it was played in the early half of the 19th century long before Doc Roberts recorded it as would be expected of a tune with a direct Irish ancestor (“Over the Moors to Maggie”). This is the only tune of Darley’s that is duplicated from the Rounder anthology (Traditional Fiddle Music of Kentucky, Volume 2: Along the Kentucky River, Rounder CD 0377), well worth getting if you can find a copy. This track is a different take, however, from the one included in the anthology.

- Billy Lost in the Lowland (C) – Now the right name of that piece is “Billy Lost in the Lowland.” Of course some of them call it “Billy in the Lowground” and all such foolishness as that. But the right name for that – when I was a kid they called it “Billy Lost in the Lowland” and that’s the way they played it. “Billy Lost in the Lowland,” that’s really the name of it. I heard my grandfather play it. My mother’s oldest brother was an awful fiddler and he played it just like I play it. I play it like they do. But they’ve changed pieces around and destroyed them, John. They’ve throwed part of that stuff away, part of the music’s throwed away, they leave it out. It’s a dirty shame the way they tore the pieces up. These fellows now don’t even play it right. There’s a place in there where the man hollers. “Billy Lost in the Lowland.”

This is the most intriguing, intense, and unusual setting of this old standard I’ve ever heard. One of the marks of fiddling excellence has to be how a gifted player can transform and give new life to a familiar tune that has lost its edge by being too well known.

- The Old Richmond Scottische (F) – Another piece that shows the light classical influence in Darley’s playing. For someone who could not read music and never took lessons, his facility with these classical-sounding pieces in the key of F is quite remarkable.

- Over the Waves (G) – Composed by Juvenita Rosas, a Mexican composer and band leader in 1889, original title “Sobre Las Olas” (Blech). Darley’s rendering of the tune shows the brisk pace that was favored by many of the old fiddlers and dancers for waltzes. This was Richard Jett’s favorite tune. Richard was the superintendent of schools in Wolfe Co. who hired me for my first artist-in-the schools residency. He was also the dance caller at Natural Bridge and a great fan and promoter of mountain music. He always called for this tune and Darley always obliged.

- Rocky Mountain Goat (D) – Also known in Kentucky as “Mud Fence” and “The Grand Hornpipe,” it was first recorded by Doc Roberts in 1927 on Paramount. Under the title “Rocky Mountain Goat,” it was widely known to both fiddle and banjo players throughout central and eastern Kentucky.

- The Grand Old Jubilee (C) – I remember one verse of it:

Old Nero was playing the fiddle over by the door.

It looked like he’d tear all the hair right out of the bow

Old Wesley was throwing hisself away on the old banjo.

Some were dancing, some were singing, the old folks were on their knees.

It just seemed like everything came down from heaven

that night at the “Grand Old Jubilee.”

Well, there’s part of that that sounds blue-ish to me. And I believe that’s the reason why, John, they was treated so bad, sold and abused, and whipped, and they couldn’t have been nothing else but somebody with the blues, people with the blues. And I believe that’s what started it, with all my heart I believe that.

Now some of them called it “Go Free, Old Slaves” and some folks called it “The Colored Folks Jamboree.” That’s when they got word, John, that slavery was over and they was having a celebration there. I always will believe that that piece and another piece I know was connected to some great colored fiddler down there because there’s a piece called “Nero the Slave” and in that other piece Nero was over by the door playing the fiddle, you see. And my grandfather told me that at the close of the war some Union or Confederate soldier must have been a fiddler that got through the war and come back into this country and brought that piece with him and heard that colored man play that fiddle.

- The Fun’s All Over (C) – Usually thought of as a West Virginia tune, there were a number of old fiddlers in Kentucky who played it. Gus Meade considered it related to the tune “Hot Corn” that also occurred throughout central and eastern Kentucky.

- The Roosian Rabbit (G) – Darley learned this tune from Bob Patton who had learned it from his mother Easter Patton who also played the fiddle. Both Gus Meade and Kerry Blech detected a relationship to two Uncle Dave Macon tunes, “Rabbit in the Pea Patch” and “Gray Cat on the Tennessee Farm.” Other Kentucky variants of “Roosian Rabbit” were played by Clarence Rigdon (Lewis Co.), John Salyer (Magoffin Co.), and J. P. Fraley (Carter Co.).

See also: Darley Fulks by Jeff Todd Titon