John Dee Kennedy of Pawnee, Oklahoma – FRC738

By Brad Leftwich

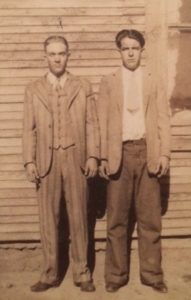

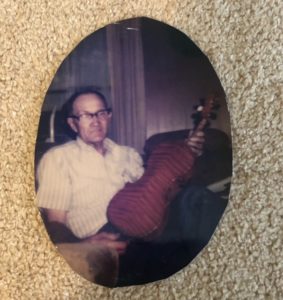

John Kennedy (fiddle) and his cousin Ed Guthrie (banjo), at John’s home in Pawnee, Oklahoma, 1982. Photo by Linda Higginbotham.

“So who do you think is the best old-time fiddler around here?” Linda and I had spent a pleasant couple of hours making music with 86-year-old Sam Pim at his home in Ralston, Oklahoma, when we asked his opinion. Although missing the tips of two fingers on his left hand, Sam was himself an enthusiastic fiddler. He also made and repaired fiddles, and had a discerning ear when it came to old-time music.

It was December 30, 1982, and we had been looking for something to do during a visit to my parents’ home in Stillwater over the holidays. We had met the day before with George Carney, a professor at Oklahoma State whose specialty was the geography of country music. George gave us a list of Oklahoma fiddlers that grad student Jim Renner had put together for a documentary project, the Oklahoma Fiddle Archive (now available online on the Slippery Hill website.

Sam Pim first directed us to John Kennedy, calling him “the best old-time fiddler around here.” Photo by Linda Higginbotham.

List in hand, we headed northeast on a day trip to Osage County. Sam Pim was supposed to be living in Hominy, so we stopped at the post office there to ask directions. Sam was retired from the postal service and had been their former coworker, so they knew exactly where to find him. They gave us his new address in Ralston, a tiny town on the banks of the Arkansas River in neighboring Pawnee County.

Sam didn’t hesitate: “The best old-time fiddler around here – that would be John Kennedy. But it’s hard to get him to play, and he won’t bear down with his bow when he does.” He gave us John’s address in Pawnee, and since the drive back to Stillwater took us that direction anyway, we stopped and knocked on the door.

A real gem

It was growing late in the afternoon, but John invited us in. Linda and I chatted with him, hoping we could get him to play a few tunes before we had to go. We made an effort to include his wife in the conversation, but, as I noted in my journal that evening, “she seemed unwell and clearly felt she wasn’t getting enough attention.” We would learn more about that situation as time progressed, but for now all was well. Better than well in fact, for John turned out to be a real gem.

True to Sam’s warning, John maintained that he rarely played anymore and was never very good in the first place. But he loved fiddling and wanted to hear us play a tune. We obliged, and then coaxed him to get out his fiddle. The few selections he played were brief and fragmentary, one time through each part if we were lucky. He scraped through them quietly, with very light bow pressure, and ended each with apologies that he couldn’t remember any tunes, didn’t play them right, couldn’t get his bow arm and fingers to work anymore, and so forth.

But what we heard was magical. Linda and I looked at each other with delight. Sam Pim had been spot-on, not just about John’s reluctance to play, but also that his fiddling was something special. We made a plan to return the next day, New Year’s Eve.

John was waiting for us when we arrived. He had one of those old cassette tape recorders shaped like a cigar box with the buttons along one end, and he turned the tables on us by saying he wanted to record some of our tunes. We made a deal that we’d play if he would, and we spent the afternoon visiting and trading tunes back and forth. It was a wonderful experience.

I’ll get back to that later, but first here’s some background that I was able to uncover about John Dee Kennedy and his music.

Kentucky and Arkansas roots

When John was born in 1914, his father, Elias Bryant (1862-1930), was 52 years old. It’s a little startling, putting that into perspective, to realize that Elias himself was born during the Civil War. He was from Laurel County in eastern Kentucky, a fiddler, and undoubtedly John’s inspiration for taking up the instrument.

The Bryants were a large family. Elias had thirteen siblings and many aunts, uncles, and cousins as well. His sister Rachel married John Will Guthrie, from another big Laurel County clan, forming a bond that would unite the two families for decades to come and through several major migrations. A considerable number of Bryants and Guthries moved circa 1890 to the rugged Boston Mountains of northwest Arkansas – so many of them, in fact, that the area of Newton County where they settled is named Kentucky Township.

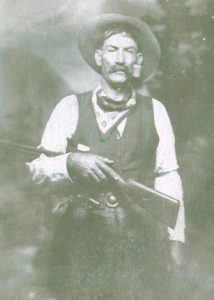

No photos of John’s father, Elias Bryant have been found. This is Elias’ brother Jesse, who made the migration from Kentucky to Arkansas, and ultimately to Indian Territory, with the rest of the Bryant clan. Photo courtesy Debbie DuBrucq.

Around the turn of the century, Elias and others of the Bryant family moved on west to the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory, where they lived for five or ten years near the town of Antlers. In 1907, Oklahoma statehood created new opportunities for white settlers in the former territory, and may have been a factor in the Bryants moving yet again. In any case, the 1910 U.S. census shows Elias and most of his extended family living in Osage County in the northern part of the state. John was born there in 1914, at the outset of the Great War in Europe.

In 1917 the Guthrie clan, after a generation in Arkansas, rejoined the Bryants in Oklahoma. According to John, nearly all of the Guthries were musicians, notably his uncle John Will Guthrie, who played fiddle, and his cousin (John Will’s son) Ed Guthrie, who played banjo. Between the Guthries and the Bryants, Osage and Pawnee counties had a strong representation of Arkansas fiddlers whose roots were in the traditions of Kentucky. John was aware of that lineage and referred to it on several occasions.

“It’s not a very pretty story”

Linda and I lost touch with John back in the 1980s under circumstances that I’ll detail below, and I was trying to discover what had become of him several years ago when I met his daughter Carol Kennedy Hendrix through an online genealogy forum. She generously shared a wealth of information about her father and his family that filled in many of the details.

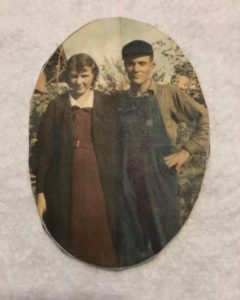

Elias Bryant’s wife, Mollie (Robinson), tolerated having his second family (the Kennedys) in her household. Photo courtesy Carolyn Kennedy Hendrix.

“It’s not a very pretty story how Daddy came into this world,” Carol told me. John’s mother was not married to his father. Elias already had a wife, Mollie Robinson, whom he wed way back in 1882 in Kentucky. Mollie had nine daughters with him and was near the end of her childbearing years when John’s mother came into the picture.

Carol related that John’s mother, Ida May Kennedy (1893-1961), had come from Antlers, Oklahoma. It’s possible that Elias first came into contact with her during the brief period when he and Mollie and their gaggle of daughters were living there. After the Bryants moved north to Osage County, the young Ida May joined them and moved in as their housekeeper.

In 1910, at 17 years of age, she and Elias had a daughter named Myrtle. Ida May went on to bear him two more children: John Dee in 1914, and Minnie in 1917. Incredible as it seems, Elias and his wife Mollie and six of their daughters, as well as Ida May and her three children, all continued living together under the same roof.

Carol expressed amazement that Elias’ wife put up with the arrangement: “I told Daddy, maybe the old lady Bryant could have forgiven the old man one time, but to have three of you? What was wrong with that old woman?” Apparently the scandal was rarely spoken of openly. According to Carol, some of the Bryants never acknowledged any kinship to the Kennedy children.

Ida May was literally young enough to be Elias’ daughter – she was, in fact, younger than several of his daughters. It’s difficult to fathom why a teenage girl would move in with a middle-aged man and bear him children in a household that already included his wife and six daughters.

Information about Ida May’s family and circumstances are scarce, but it’s likely she had little choice in the matter. One imagines she was either orphaned or trying to escape an even worse home situation. Life in Indian Territory could be hard. Mortality was high, and people did what was necessary to survive.

Carol said her father often described how hard life was growing up in that household. “His dad would send him out hunting with maybe four shotgun shells, and if he came back with less than that, he’d better have a squirrel or rabbit to show for it or he’d get a whipping.”

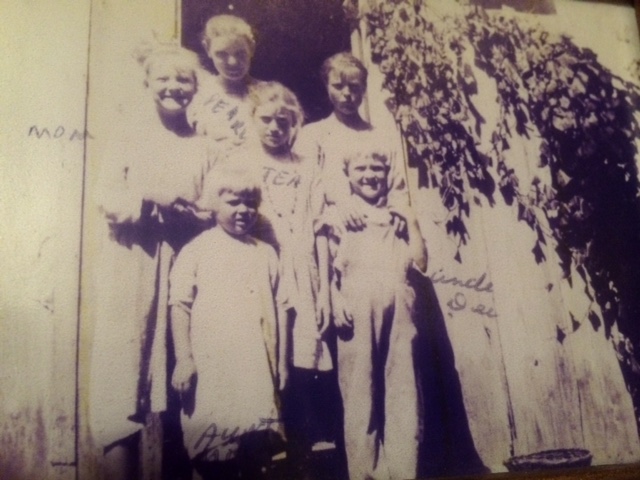

About 1920. John is at lower right; his mother Ida May Kennedy is behind him with hands on his shoulders. In the center is John’s half-sister Leona Bryant (nicknamed “Tea”). Lower left is John’s sister Minnie Kennedy. At left is John’s sister Myrtle Kennedy, and in back is his half-sister Pearl Bryant (who married Toney Adams). Photo courtesy Carolyn Kennedy Hendrix.

Getting started on the fiddle

On at least one occasion, Elias showed John more kindness. Carol described how her father got started playing the fiddle:

“He told us, you know, his dad played the fiddle, and he used to hang it on a nail on the porch, and when Grandpa would leave to go into town, or go hunting or check on the cows or whatever, Daddy would sneak down his fiddle to play. Then he’d watch for his dad to be coming back across the pasture, and when he’d see him, he’d put it up real quick.

“He said one day his dad left, and Daddy was on the porch playing his heart out when Grandpa circled round from the back and scared the you-know-what out of him. Daddy told us ‘I just knew I was gonna get the whipping of my life.’ Well, Grandpa just laughed and said, ‘I figured you had been sneaking around with my fiddle!’ But instead of whipping him, he sat down and started teaching him how to play it.

“So when his dad died, he got his fiddle. He said the fiddle had all mother-of-pearl inlay on the back, and some on the front. He said it was the most beautiful fiddle, and he had it for years and years. But when he and Mom got married in 1937, times were tough. He was down on his luck and didn’t have a job, so he went into Ponca City and pawned the fiddle. And I think he only got like $20 or $25 pawn on it or something. And he picked it up a couple of times, only to pawn it again, and then eventually he lost it. He said he regretted that all his life.”

Forced from his home

When Elias died in 1930, the household split. His wife Mollie and her children moved in with their recently married daughter Leona in Cleveland, Oklahoma. John’s mother Ida May moved in with her eldest, Myrtle, also recently married and living in Skedee. The 1930 census shows that John and his sister Minnie initially came with her, but the newlyweds apparently couldn’t support three dependent relatives of the bride and John was forced out at the age of 15.

Carol says he then shuttled among different relatives. Although it must have been a difficult time, that period between the breakup of Elias’ household and John’s shouldering of the responsibilities of married life in 1937 presented some of his best opportunities to grow as a musician.

At various times he lived with his half-sister Pearl Bryant and her husband Toney Adams (see below), who was one of the best fiddlers in the area; with his half-sister Dora Bell Bryant Casey, whose son Carl (see “The Music Scene in Pawnee and Osage Counties”) was, among other musical talents, an excellent guitar player and who in later years became John’s main backup; and with the Guthries, another family of musicians. John’s aunt Rachel Bryant was married to fiddler John Will Guthrie, and their banjo-playing son Ed (see “The Music Scene in Pawnee and Osage Counties”), John’s cousin, seconded John at many dances over the years.

Musical influences

Tom and Toney Adams. John was born in the Osage County town of Avant and grew up in Boston Pool, an oil boomtown of which all that now remains is the graveyard. During John’s growing-up years, the nearest community of any size was Cleveland, a small Pawnee County town on the Arkansas River. A number of good musicians lived in the area, but in particular John credited Tom and Toney Adams – especially Tom, who was Toney’s uncle – as his mentors, and under their tutelage John’s fiddling really began to take shape.

During a conversation about the Adamses and what they taught him, John told us:

“There’s so many people that plays them old-time tunes, and they don’t get that bow action. I used to sit down and play with [the Adamses], you know, and when I made a mistake they’d stop me right there: ‘Now whoa, now, back up now, let’s get that right,’ you know, and they’d show me how, and I’d keep on. At first, for a long time I couldn’t use that bow, no way, hardly, you know, maybe a waltz or something, just straight bow. And they told me, of course, that I’d never make a fiddler – that is, a breakdown fiddler, just waltz. But then they got after me to learn that bow action.”

The old man, George Thomas “Tom” Adams (1880-1972), was born in southern Missouri. The family spent time in western Arkansas before winding up about 1891 near Heavener, in what was then the Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. Tom’s nephew Toney (1900-1974) was born there, but he and Tom and a number of other members of the extended family had moved up to Pawnee and Osage counties by 1912.

Toney Adams married one of John’s half-sisters, Pearl Bryant, and John lived with them for a time before his own marriage. According to John, “He was a real good, smooth, all-around fiddler of most any kind. He had Tom beat [on waltzes and slow pieces].”

Tom Adams, on the other hand, “was about the best old-time breakdown fiddler I ever heard… He was fair on waltzes, but I mean he was just excellent on breakdowns!” John especially admired and emulated Tom, and over the years played a lot of music with him. He told us that the old man carried his fiddle to dances in a flour sack, and the first tune he’d always play whenever he picked it up was “Durang’s Hornpipe.”

“He was pretty old when I started kindly [kind of] playing around with him. I was just a big old boy, and I expect he was, oh, to start out with I imagine he was in his fifties. I played on with him till he died. When he died, heck, he must have been 85 or 90 or something like that.” (According to the Find A Grave website, he was 92.)

Toney and his wife Pearl (Bryant) Adams. John was influenced by Toney’s fiddling, especially during the time before his marriage when he boarded with them. Photo courtesy Houston Adams.

John mused, “He was crazy about fiddling.” In his old age, Tom developed palsy (as John quaintly expressed it, he got “nervous”), but couldn’t bear to give up playing the fiddle. “He got so nervous he couldn’t play like he had been, right-handed, and he switched over left-handed. He was a little steadier left-handed. But he just got to playing pretty fair left-handed when he died.”

John played a tune he learned from Tom that he simply called “Old Man Adams’s Tune.” Once after playing it for us, he recalled,

“I don’t know [the name of that]. The old man Adams, that old booger was pretty near 90 years old, and he couldn’t play a fiddle, he got too nervous. But that particular tune, he told me, said, ‘I want you to learn that.’ And he just kept on at me; he got to where he couldn’t play at all, but he’d hum it to be sure I could get it started, said, ‘now be sure to—I want you to learn that tune.’”

Both Tom and Toney Adams have carvings of a fiddle and bow on their gravestones in the Cleveland cemetery.

The unknown fiddler in the Skedee jail. Sometimes an unpleasant event can have a silver lining. In addition to what he was learning from the Adamses, John got an unexpected intensive workshop in how to use the bow as the result of one such event. He related the story:

“I lived over here at Skedee, a little town back over here [in Pawnee County], and there was two brothers and one cousin I think it was, they got me in some trouble one time; got me in jail. What happened was one of these old boys and I walked up town one night. All the boys would meet up there, and they’d box and wrestle.

“One old boy asked me if I’d help him a few minutes, and I said ‘yeah.’ We just walked down the street; the sidewalk’s kinda high there, kind of a ditch or something. He just reached over the side of that and picked up a ten-gallon cream can, and it was full of gasoline. I didn’t ask him what was in it. He just picked it up and set it on the sidewalk. I got ahold of one handle and helped him carry it up to the house.

“I had a job up at Hominy, and I was to go to work the next day, but the law come and got me. Those boys got caught stealing gas, and they told that I’d done it.

“But anyway, I spent seven days up here [in jail]. They was a guy in there played the fiddle. He couldn’t note his fiddle very good – he had the fiddle there in jail – but boy, he could use that bow! And that’s where I learned to use my bow, sitting and watching him. So I guess that was worth me being in there. That’s mainly where I learned to use my bow.

“Never did see him no more after that. I don’t know who he was or nothing, but I’d sit there for hours, as long as he’d play on that old fiddle. I played the fiddle some, but I couldn’t use my bow right on those breakdowns. Well, I set there and watched him, and then I’d take it and then I’d try it, and I’d keep on until finally I got the hang of how to use that bow.”

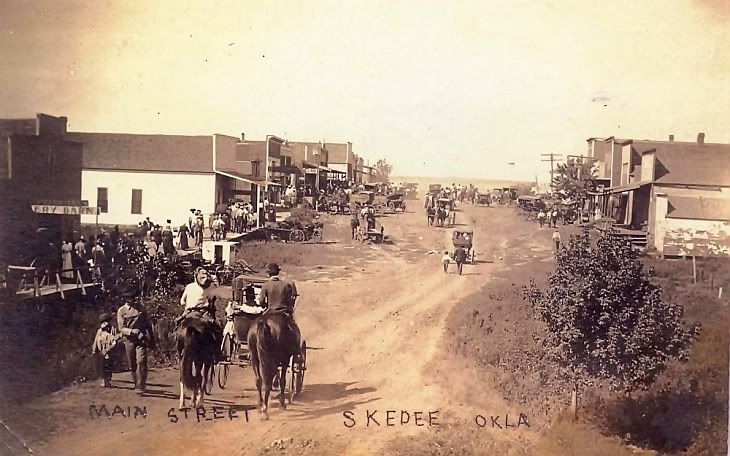

Skedee, Oklahoma, a few years before John was born, hadn’t changed much from pioneer days. John spent a week in the Skedee jail as a youth for a minor crime he didn’t commit, but he learned something about bowing from another inmate who had a fiddle. Photo courtesy the Ralston Foundation.

Juggling music with family and work

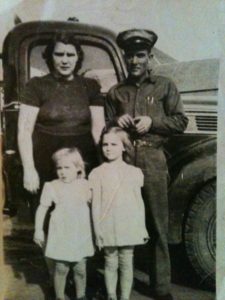

In 1937 John married Leona Arnold. He was 23 years old and she was 16. According to Carol, he was working as a farmer when their first child was born in 1938, sharecropping on his father-in-law’s land in Blackburn. The 1940 census has them living with two infant children near Ponca City, in neighboring Kay County, where John’s occupation is listed as “odd jobs man.”

Carol recalled, “I always heard him talk about how he used to play for a lot of barn dances when they was younger, and Mama said she’d always remembered him doing that stuff, but that would have been way before I was even born.”

John continued playing for dances for several years after their marriage, but in the 1940s began getting work as a truck driver, which put a damper on his music-making. He told us, “I drove a truck about 25 years … wasn’t fiddling at all, you know, and then when I did come back, tried to come back, there’s so many of them [tunes] I never could think of anymore.”

As John struggled to support a family that eventually grew to six children (Helen, Patsy, Daryl, Roy, Carol, and Pam, born in the years between 1938 and 1957), his life became a dizzying sequence of relocations and job changes. Carol says that for the most part he drove trucks hauling gas from a variety of bases in Oklahoma and Kansas – “we were always moving back and forth, Kansas to Oklahoma, Oklahoma to Kansas” – although other ventures were interspersed.

In 1958, for example, they moved to Illinois where John made a short-lived attempt to start a blacksmith shop with his brother-in-law. In 1960 they spent a summer picking peaches in California, where another daughter lived. In 1962 they were back in Oklahoma with John driving a hay truck and a school bus. In 1963 they moved outside Pawnee where John was trying to buy a service station; and when that didn’t work out, in rapid succession, Sand Springs, Kansas City, and Tulsa.

Through it all, Carol considered the place they had on her maternal grandparents’ property near Blackburn, Okla., to be their “real” home, one they came back to time and again: “I always remember living in Grandpa Arnold’s house up on a hill in the pasture near Blackburn.” It was a stable point of reference in an unsettling string of moves, and the setting for many happy childhood memories. Carol recalled,

“I tell people we had ‘four rooms and a path’ – no indoor plumbing. On Saturday nights, Mama would make fudge and Daddy would play the fiddle. And I can remember, when I was in first grade, Daddy came in with this reel-to-reel tape recorder. And Mama was kind of laughing, ‘Now what did you go and spend money on that for, John Dee?’ So I remember Daddy playing fiddle into that, then he handed me the microphone and said, ‘Here, sing for me!’ I can remember that like it was today, singing, ‘I love my daddy, I love my daddy!’”

I asked Carol if her father continued playing for dances when she was young. She answered,

“No, I always heard Daddy talk about that, and I used to laugh, because when I was a teenager I used to just love to go dancing. And Daddy would disapprove of us going to dance halls. My aunt Minnie told me ‘Well, your daddy has no cause for talking, he used to play at them.’

“They had this place in Fairfax called Jumps, used to be Jumps Skating Rink, then Jumps Cafe. Well on the third Saturday, back in the ’50s, ’60s, they always had dances there. And my dad sneaked off with his cousin, and he would tell Momma they was going fishing. And my two cousins, Barbara and Sue, they’d sneak off and they would go up there dancing on a Saturday night, and they’d run into my dad up there! He used to play some there, a little bit. Daddy would get onto them, and they’d say, ‘Well, we won’t tell Aunt Leona if you won’t tell on us.’ He wasn’t never flirting or anything, but he just didn’t want Momma knowing he was there, you know.”

John’s oldest daughter Helen recalled that in the early 1950s, when they were living Lyons, Kansas, an area radio station had heard that John was a really good fiddler who played at local barn dances. They tried to recruit him, but he was too shy to play over the radio. So they invited him to the station with several other fiddlers and tricked him into playing, thinking it was just an informal tune-swap among fiddlers. After he played a tune, John was mortified to learn that he had just been broadcast live over the air.

Twenty-five years of driving trucks left John with serious chronic back pain. By 1965 he had to find other work. Although jobs were hard to come by, he eventually was hired at McKee’s Sewing Center in Tulsa as a sewing machine mechanic, “flying by the seat of my britches” as he taught himself to repair sewing machines on the job. Mrs. McKee said he was the best mechanic they ever had.

Eventually John and his wife Leona settled in Ralston. They lived there until 1978 or 1979, when John sold the house to Sam Pim (the same house where we first visited Sam a few years later) and they moved to Fairfax. It was about that time they discovered that Leona had cancer. She passed away in February of 1982, leaving John bereft and hardly knowing what to do. He determined to marry again as soon as possible.

There was a woman who had hired John to do odd jobs, and brought food to the house while Leona was bedridden. According to Carol, “she made statements around town that when my mother was gone, she was going to marry Daddy.” Word got back to Leona, who put an end both to the odd jobs and the food delivery.

But in May, only three months after Leona’s passing, John announced that he was marrying this woman and moving with her to Pawnee. “I about had the big one,” Carol told me. “I cried and told him she wasn’t a good person, to please think it over, Momma hadn’t been gone that long and he was just lonesome. I begged him to move in with us, but he was headstrong.”

Enter Brad and Linda

So that was how things stood when Linda and I first stumbled onto the scene only seven months later, in December 1982. We had no idea they had been married less than a year; we didn’t find out until I met John’s daughter years after his death and she set us straight.

Perhaps we were too effusive in our praise of John’s music on that first visit, although I don’t think ultimately it would have made any difference. As we played music in the small dining room, it became apparent that the fly in the ointment of our delight was the brooding presence of his wife, sitting in the adjacent living room. Mostly she sat in silence, but occasionally she would interrupt the music, shouting a criticism or reminding him of some chore. We weren’t sure how to react. We offered to leave, but John insisted that it was nothing, he could take care of it later, and that we should stay a while longer.

At one point Linda, hoping to ease the tension, went into the living room and visited with Mrs. Kennedy about household things. She showed Linda family heirlooms and talked about her father, whom she said had been a musician. She then raised our eyebrows by declaring, in front of John, that he was nowhere near the musician that her father had been. She warmed to her topic, insulting and tearing down John’s fiddling. When John tried to speak, it was not uncommon for her cut him off, saying, “oh, shut up.” John just laughed it off, but we found it pretty uncomfortable.

Whenever we visited my parents in Stillwater during the next several years, we would make a point of trying to get together with John for some tunes. It became harder with each visit as his wife grew more openly hostile. When she could intercept our phone calls, she would tell us he wasn’t home. We tried arriving unannounced; if she answered the door, she would tell us he was too busy to play music. On the occasions when we managed to get John on the phone, we made plans to meet him elsewhere. Once he came down to my parents’ home; another time we met at the home of Roy Herndon, a mutual friend about John’s age who lived in Stillwater and played clawhammer banjo.

It began to feel like we were having a clandestine love affair. We did in fact love John’s fiddling, and the combination of his natural reluctance to play and the subterfuge involved in trying to circumvent his wife’s wrath made the music we were able to play with him seem especially sweet. We could never seem to get quite enough.

The northern Oklahoma music circuit

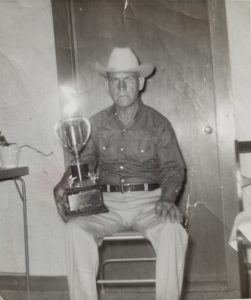

John competing at the Labor Day fiddle contest in Ralston, Oklahoma. Photo courtesy Carolyn Kennedy Hendrix.

At the time, a music circuit of sorts existed in that part of Oklahoma: Wednesday in Stillwater, Thursday in Ripley, Friday in Ingalls, Monday in Perkins, and several others that I don’t recall, nearly every evening of the week. Amateur musicians ranging from high school kids to retirees would gather in a senior citizens center, community center, or service club hall. There would be a stage area with a small sound system, and the format was usually an open mic jam with different people taking the lead and others participating as they were able. The music ranged all over the spectrum: country, bluegrass, gospel, even some pop and rock and roll. Instrumentation could include electric and acoustic guitars, accordions, electric organs, tenor banjos, horns, and drums, with plenty of vocals in the mix.

Fiddlers in the area knew each other and enjoyed getting together. There would often be two or three at these gatherings, so we might hear a few fiddle tunes in the course of the evening. In attendance at various times were Floyd Hillhouse, a bluegrass fiddler who looked to be in his forties or fifties and whose band had a semi-regular gig at the Cimarron Ballroom; John Bunney, a “waltz fiddler” in his late 60s from Stillwater who played at nursing homes with Roy Herndon backing him on guitar or banjo; Dale Carothers, also in his late 60s, an old-time fiddler from Ripley who was a pretty good hand at backing up singers and who would stay on stage most of the evening accompanying just about everyone who performed.

The day the music died

John Kennedy sometimes came to these events, although not so much since he had remarried. When he would show up, Roy Herndon and Dale Carothers, who appreciated his talent, made sure he played on stage.

In December 1985 we got a call from Roy that John was planning to be at the gathering in Ripley on Thursday evening, so we drove over from Stillwater. The show was in progress by the time John arrived; Roy got him up on stage and backed him on guitar. John fiddled “Grey Eagle” a couple of times through and turned to go, leaving the audience wanting more as usual.

Off the main hall was a kitchen area that served as a greenroom. Linda and I headed backstage to catch John before he put away his fiddle. He was glad to see us. Roy and Dale were also in the kitchen, and we decided to play a couple of tunes there just for our own enjoyment.

In the middle of the first tune, the door flew open and in stormed John’s wife, hopping mad. She upbraided him as a “no-good musician” and demanded that he stop this nonsense and take her home immediately.

Dale tried to defuse the situation. He raised his hands in an appeasing gesture and, mustering his most soothing tone of voice, began, “now, now, John doesn’t get to play much and we want to encourage him…” He might as well have thrown kerosene on a fire; she wheeled around and let him have it with both barrels: “No we don’t!” she exploded. We were dumbstruck as she chewed out the lot of us with choice language and then dragged John from the room. As he passed through the door, he looked back at us helplessly. It was like watching a struggling swimmer disappear beneath the waves.

At that moment Linda and I realized we were defeated. We never made another attempt to visit John or play music with him. A few years later my parents moved away from Stillwater, driving the last nail in the coffin.

The end of the trail

I didn’t have occasion to return to Oklahoma again until the early 2000s. I had business in Winfield, Kansas, and one Sunday afternoon I drove down to Pawnee to see if, by any chance, John were still there—uncharitably harboring the hope that he had outlived his wife. No one answered my knock at the door, no sign even that anyone lived there.

For years after, I periodically searched the Internet for an obituary or some other indication of what had become of him. Finally, in an online genealogy forum, I saw a post from his daughter, Carol Kennedy Hendrix, whom I had never met. We corresponded, and she was quick to clarify that the wife with whom Linda and I had had such a bad experience was not her mother. She generously shared a trove of information about her father’s life as well as the manner of his death.

On Christmas Day of 1996, Carol said, she got a call from her sister Patsy that she needed to come to Pawnee right away. Patsy had gone to her dad’s to cook Christmas dinner and found him with a huge knot on his head and “talking crazy.” John’s wife said she thought he had fallen out of bed. The daughters bundled him off to the hospital, where the doctor said he had been hit with something hard and had a concussion.

Carol and her husband returned to the house and confronted the wife, who then said John had fallen down some stairs during the night. Carol’s husband searched the house and found a blackjack concealed in a boot in the closet.

When John was coherent again, he told Carol he remembered getting up during the night and encountering his wife, who tried to make him go back to his room. He said he thought she hit him with something, and he couldn’t remember anything after that.

The doctor sent John to the nursing home for an estimated six weeks of rehab; but John had previously been diagnosed with signs of dementia, and his nursing home experience was not a good one. He never completely recovered and passed away on May 12, 1997. Carol told me,

“You know what’s funny, Brad, when he was in the hospital, and he was really bad—this was probably three or four days before he actually died—he got to the point where he could hear music but just couldn’t respond to it. And the Hospice lady was telling us different ways people try to communicate. So we got his little tape recorder and we put it there by the bed, and we put on one of his fiddling tapes, and he just lay there listening. I told him ‘Well, Daddy, we’re going to go eat a bite of lunch, and then we’ll be right back,’ and I turned the recorder off. And boy, his old foot was just a-patting that bed you know, and ‘look at that! What in the world?’ He just kept a-patting. So I said ‘Daddy, do you want me to turn that recorder back on?’ And boy, that old foot would really get to going. So I’d turn the recorder back on, and his foot would stop. And the Hospice lady said, “Yeah, he was letting you know that he liked that.” So I just let it run. I thought, ‘oh, he was just the sweetest little old man.’”

Keeper of the flame

As mild and self-effacing as John Dee Kennedy was, Linda and I always marveled at how he stuck to his guns musically. Most fiddlers his age in Oklahoma then, as now, were playing Texas contest style, Western swing, bluegrass, or commercial country music. Like them, John had access to what was popular on the radio when he was young: Bob Wills, Arthur Smith, and other stars of the airwaves had a big impact on fiddlers of the day. But instead, John chose to perpetuate an older family and community tradition. He was attracted to the noncommercial breakdowns and dance tunes played by musicians a generation or two older than himself, and he went out of his way to learn from them, keeping alive some of their vintage tunes that others had stopped playing. And he never deviated. Even though he was self-conscious that it was out of step with modern trends, he never tried to change in order to please anyone else.

John never knew how much of an influence he had on me. I continue to play the many tunes I learned from him, and I have often incorporated his distinctive take on common tunes I already played. Whenever I can, I pass along to other fiddlers what he taught me, and hope his legacy will live on in that way. I like to think he knew he was part of something larger than himself, as we all are, and that it gave him some satisfaction.

*****

Look for this article in an upcoming Fiddler Magazine.