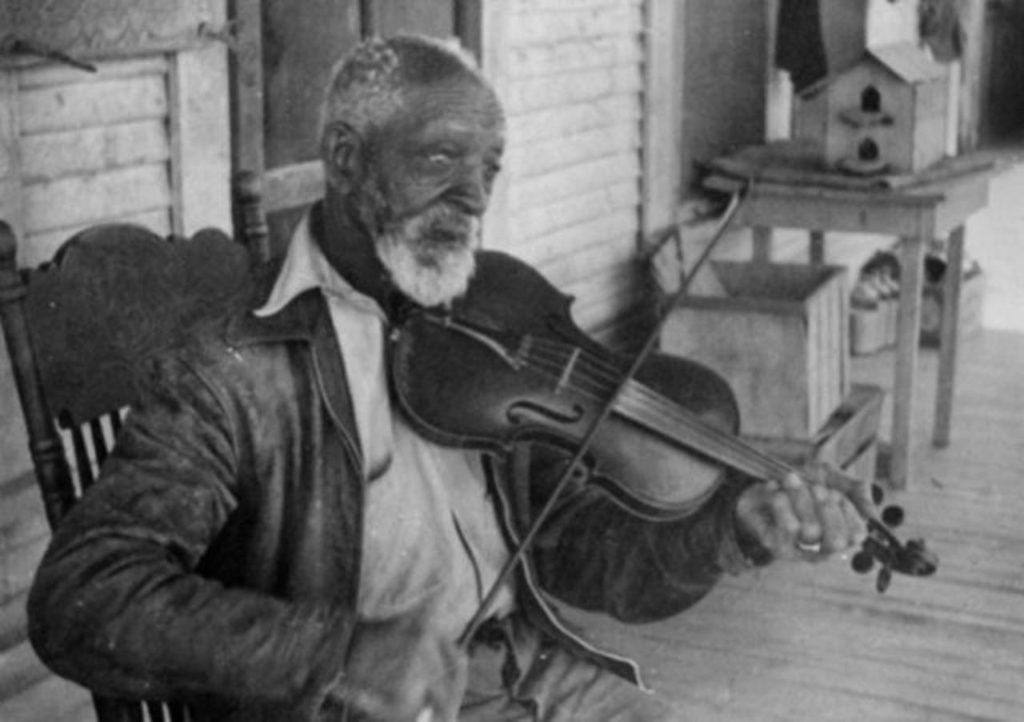

Teodar Jackson – African-American Fiddling from Texas – FRC728

by Dan Foster

Teodar Jackson (1903-1966) was an old-time fiddler with deep roots in Texas. He was born in Gonzales County where his family had farmed since his grandfather came there from Mississippi sometime after the Civil War. African Americans numbered roughly a third of the county’s population in the 1880s. Communities like Wesley Chapel, Monthalia and Canoe Creek were small rural sanctuaries where many young musicians came of age to the sound of old-time fiddling at dances and country suppers. By the 1940s the family had moved north to the Austin area where Mr. Jackson remained a fiddler known to all as “T-olee” and to family as “Papa-T”. Familiar dance tunes, blues and rags made up a large part of his repertoire, but in addition he played a number of set-pieces that hint at something perhaps older, otherwise lost to our ears, until his playing was recorded by Tary Owens in Austin in 1965.

Gonzales County and the surrounding area in south Texas is known to have long been home to a number of African American musicians from before the 1850s. Tommie D. Wright, a noted member of what has been described as “an enormous clan of Texas fiddlers”, learned the music from his father and grandfather, Jack Wright who was born in Gonzales County in 1845. As indicated in the book Blues Come to Texas, Jack Wright used to fiddle and call set for eight men and women all “out on the floor dancing squares”. He fiddled tunes like Sally Goodin, Old Hen Cackle, Pick the Meat Off the Devil’s Backbone, Sally in the Wildwood, Green Corn and others.

Little is known of Teodar Jackson’s early years. By 1880 census records indicate that his father, Caldwell Jackson was living with his parents Nep and Peggy Jackson in Gonzales County. Caldwell had five brothers and two sisters. His son Teodar was born September 6, 1903. By the time the Jackson family left Gonzales County, there were eight children.

By 1942, Teodar’s family was living near Round Rock, Texas. Later they moved to the St. John’s area then in northeast Austin. By 1944, they were living at 2008 Concho Street, the present site of the Red McCombs Field baseball stadium. The surrounding area had a troubled history. Fifteen years before the Jackson’s moved to there the area, anchored by a black orphanage founded in 1907, had been targeted by the City of Austin in 1928 as part of a master plan to relocate African American families from parts of Austin where many had lived in semi-autonomous “freedman” communities such as Wheatville, Clarksville, Robertson Hill, and Masontown since emancipation. The 1928 plan legally segregated a largely rural area near the site of the old orphanage across East Avenue, now Interstate-35. The city had decided as part of its plan not to provide sewer lines or paved roads to the established black communities in West Austin, forcing citizens in those communities to relocate to East Austin, a “negro district” with at least some basic city services provided. Over time, the plan largely had its desired effect. The refugees did the best they could to build a new community in the fractured, artificial district despite red-lining and continued discrimination by the City.

“It’s like they dropped us off here and forgot about us.” —Eva Lindsey

The artificial nature and difficult circumstances in the area, a well-known problem, caused it to be shunned by some long-time residents of the few remaining free communities like Clarksville who refused to be displaced. The area’s difficult circumstances resulted in chronic instability and frequent violence. The new neighborhood must have been a challenge to the Jackson family. Their roots had been in the rural area of Gonzales County about 70 miles to the south of Austin where, like other centers of rural population during and after Reconstruction, blacks were driven to the margins by legal proscriptions and tended to populate smaller, outlying satellite communities for safety and some measure of self-determination. From Shankville in deep East Texas’ Newton County to Kendleton in Fort Bend County south of Houston, or Coxes Providence near present day Rockdale, African Americans managed to build and maintain communities apart from the white power structure.

We can barely imagine what life must have been like in these islands of normalcy, or how everyday life, courtship, house-building, the rearing of children, cooking, preaching, hunting, farming or music were done.

“Saturday night Country Suppers. Sometimes they were called “country balls.” Often times, just to get to the country ball, some packed their dress-up clothes in a waterproof slicker and swam the Yegua or Brushy creeks or the San Gabriel River. When the fiddler, the guitarist, banjo and piano players struck up a sad blues tune, or jazz number, those who wanted to dance did the “barrelhouse”, Charleston, tap dance, buck dance, two-step or wopsy were popular. Music was more or less a natural for many of these musicians were self-trained and played by ear, or according to their feelings, cares and woes.”

—Miss Susie Piper, Principal of Aycock School, Rockdale, Texas

Susie Sansom Piper (1921-2019) was Principal of Aycock School in Rockdale, a devoted educator and local historian. She recounted stories about “country suppers” often held near free black communities like Coxes Providence, Griffin Chapel and others in Milam and Cameron Counties. Miss Piper’s father, Paul or Julius Moultry, was a blacksmith. He operated the oldest black-owned business in Rockdale. He and his sons were also musicians. The Moultry Brothers Orchestra played music for many years in the area, sometimes being joined by Austin piano player Roosevelt Williams, known as “Grey Ghost”. Like many others they often played Saturday night country suppers.

After World War II, Teodar is known to have been playing with Alfred “Snuff” Johnson and harmonica player Ammie Deaver around Austin. Johnson was later recorded by Tary Owens. The Eighth of January, Drunken Hiccups, and Whoa Mule are all titles familiar to old time fiddlers across the country. Other tune-names like Old Aunt Jessie or Golden Slippers share a generally familiar place in the vague lexicon of common memory. But as each of these titles and others that came to life under Teodar Jacksons’ bow are heard they impel an appreciation of something unique and not found elsewhere. Played again here, they reveal echoes from a different and all but unknown realm of expression, part of our fiddling heritage restored. Growing appreciation in the 21st century for the foundational aspect of African American fiddlers in old-time music fuels the search for understanding, but always runs up against a hard barrier in the attempt to find anything meaningful to say about how the music actually sounded.

Noted record collector Marshall Wyatt states, “Black fiddlers, still common in the South throughout the 1920s, were not entirely ignored by the record industry, but they were sadly under-represented”. Thus one important avenue of discovery was largely and purposefully closed to us. By the 1920s the almost mythic “negro fiddler”, still integral to the notion of a richly imagined, grotesquely romantic Southern past, was even then wearing thin. Commercial interests and social prejudice in the early 20th century combined to set aside a large part of our musical heritage just at the time technology was beginning to enable the possibility of capturing something of its nature. Many of those who did know and understand the music best, with fondness and\or fatigue, were at long last able to begin thinking about making the turn toward a future in which nostalgia would have little part. The thirst for nostalgia was almost completely owned by white culture and catered to by the industry even while its primary focus shifted toward sounds at the birth of new musical forms across the board, blues, country, swing, and jazz. The beauty of old-time African-style fiddling “in the rural” went largely unnoticed as it began to disappear.

“The State Fair grounds are illuminated by over 1,000 torches, and the grounds are lighted from the north inclosure to the race track. Five hundred ladies and gentlemen are attending the dancing going on in the State Fair Pavilion, and three hundred are at the dance in the main exhibition hall, where two Negro fiddlers and one prompter are officiating.”

—Galveston Daily News 5 May, 1874.

Given the history of African people working, building, creating and living in North America from at least the mid-17th century, it is not unreasonable to fix the beginning of their deep influence on its music at a date not much later than that. In the American slave-based economy, the services yielded by bonded peoples were economically integrated at most levels of the social hierarchy. From field hands, house-servants and overseers to master carpenters and masons, decorative artists and musicians, bonded people provided for a wide range of needs their masters were unable or unwilling to supply themselves. Coerced into providing musical services, Africans soon managed to become masters of all they saw in that realm as their efforts began to largely redefine popular music in America. While accompaniment to dancing might often have originally been supplied by a single fiddler, it is natural and obvious that an ensemble of musicians would be preferable. According to Dena Epstein in her seminal work on the origins of banjo music, slaves were combining the fiddle and banjo at least as early as 1774. So we might hazard that the groundwork for much that has followed dates to a time at least contemporary with our national beginnings if not considerably earlier.

Bowed instruments like the fiddle, at least in the western tradition, are reputed to be traceable back beyond the edge of human memory to mythic times on the Indian subcontinent to an instrument known as the Ravanahatha. According to the Ramayana epic, after a war between the Hindu deity Rama and the god Ravana, one of his consorts brought the instrument to northern India after the fight was over. From there it might have spread north through Central Europe and south to Africa spawning generations of fiddlers on an endless variety of bowed instruments in all directions.

Whether the Bulgarian gadulka or the rebab favored by Arab Bedouins owe their existence to a Hindu god or not is difficult to say. But from time out of mind musicians in the savannah and forest lands of West Africa have played bowed stringed instruments. From the nyanyeru and gondze in Gambia or the goge among the Hausa people of northern Nigeria. According to ethnomusicologist Jaqueline Cogdell Djedje, the family of “bowed lutes” has long served musical and spiritual needs as well as symbolizing political authority and ethnic identity in the region. The same areas from which the slave trade drew its human resource. It is not unreasonable to suppose that many of the musicians inevitably among the bondsmen were fiddlers long before they ever saw a violin.

The fiddle arguably would have been the instrument of choice for black and white country musicians alike from the 1600s until the early decades of the 20th century. In the first settlements of Texas, “[h]ornpipes, strathspeys, jigs, and reels”, as recalled by Noah Smithwick, were the music of choice played on the violin. That old stock of tunes was an integral part of Anglo-American social life for not tens, but hundreds of years, enduring like the community dances that survived on their own terms into living memory. In the 1920s, when the first recordings were made of African-American fiddling, this venerable tradition was still alive, supporting a stock of tunes that was still the common source as it had been from the earliest times.

Printed recollections and accounts from early days provide engaging if silent testimony. An account of the early days of Louisville, Kentucky from the family papers of Alfred Pirtle (1837-1926) relates the story of:

“…a house warming party on the night of December 24, 1778. In attendance was a dancing master from France, whose attempts to instruct the youthful party in the graceful steps of the latest Parisian fashion met with little success”. It is further recounted that there was present “…a Negro named Cato… [who] had learned of the fun going on in the blockhouse and was ready when the young men hauled him upon the floor. All were soon dancing to the music he had learned away back in old Virginia, and a merrier party never welcomed the coming of a Christmas day”.

Simon Bronner in his book Old-Time Music Makers of New York State concerning the history of fiddling and dancing in New York State, mentions Alvah Belcher (ca. 1819-1900), an African-American fiddler who played for dances in Delaware County, New York, through the late nineteenth century.

William Sidney Mount (1807-1868), who lived on Long Island and was himself a fiddler, painted many musical subjects. Among them are several now iconic portraits that attest to the interplay between black and white musicians in New York during the period. Paintings like “The Bone Player” (1856) and “The Banjo Player” (1856) and “Right and Left” (1850) have attained iconic significance in our time. Intervening years saw the wholesale appropriation and transformation of the banjo by white musicians and the problematic rise of the minstrel show phenomenon. By the late 19th century two strains of African music were at the heart of the American experience: one, largely the provenance of black people, was plowing new ground from the blues to ragtime and jazz, while the other adapted and beautifully refashioned, mostly by whites, re-invented a newly imagined past that was at once real and illusory, nostalgic and inventive.

After the changes wrought by rapid industrialization, with the horrors of the First World War in its wake, the early 20th century almost inevitably entailed an intrinsic need, an irresistible longing, attraction and nostalgia for “simpler times”. This illusory disposition left white culture open to a thinly veiled proto-fascist agenda on the part of wealthy industrialists like Henry Ford, an anti-Semite who sought to exploit this vulnerability in order to preserve class position and protect the ascendancy by vilifying the new trends and instead promoting what he called “wholesome American values” among the poor and middle class whites to ward off any prospect of revolutionary change.

African American mass culture, at least in the 20th century, seems to share none of this desire to look backward and identify with “the good old days.” Perhaps that is because for us, the old days were not very good. I grew up knowing relatives whose parents had been slaves. Nostalgia for the past seems not to be a major part of Black general culture, especially musical culture. This is especially true in regard to aspects of culture that symbolize the Southern rural past, the other racial side of the past that Country music and old time music folk look to.

African American folk fiddling disappears as part of this cycle. Black fiddling was fairly popular in the 19th century and in the early part of the 20th Century when string band playing and dancing were dominant in rural Black communities. Even when the blues and its own dancing replaced the older music starting at the turning of the century, fiddles, unlike five-string banjos, tended to be included in blues bands, and to accompany solo blues artists on records. Yet, in the 1940s when blues bands went from being acoustic band to electric, with the exception of a great few, Black popular fiddling disappears. —Tony Thomas “Why Black Folks Don’t Fiddle”

Though Henry Ford, engineer, factory owner, and inveterate racist (not known for his sense of irony) did endeavor to co-opt the values of the waning traditional culture which his own industry was setting about trying to destroy, there was in fact still both a genuine and persistent if not vibrant musical heritage at the root of his misguided fantasy.

At the turn of the 20th century crowds numbered in the tens-of-thousands at events like the Old Fiddlers Carnival in Dallas April 6-7, 1900. The Fiddlers Carnival opened with a welcome from the trumpet corps to start off a full day of competitions and entertainments, closing out with tribute to “the old negro fiddlers”. —El Paso Herald, March 1, 1900)

Despite Ford’s best efforts in the interest of racial purity, both black and white musicians continued to grow in largely undocumented association, cobbling together the roots of hillbilly, country, rhythm & blues and rock &roll. These musical forms are hopelessly entwined at the root, deeply frustrating hide-bound purists on both sides of the racial divide up to the present day.

Uncle Homer Walker used to play a lot with white fiddlers Henry Reed, Buddy Thompson, and Harrison White. He also talked about the music he heard and played in the coal-fields of West Virginia when he worked there in the teens; there were many musicians, black and white, and many different kinds of music. —Robert B. Winans

As Paul E. Wells observed in his work Fiddling as an Avenue of Black-White Musical Interchange,

Slave owners used skilled bondsmen as musicians from at least the mid to late 17th century. While the economic advantage of unpaid labor might be a compelling reason, still the pay for free musicians would likely not have been a prohibitive factor. It is not unreasonable to consider that the novel, if not exotic renditions of the prevailing popular repertoire by Africans made them both the logical and artistic choice. “Negro Jigs” almost certainly did not conform to the stylistic expressions of white tradition, and might in the New World have had a special appeal to Americans as they sought to differentiate themselves from an oppressive past.

African stylings and the near magical bowing patterns black musicians brought to the fiddle, driven by the compelling rhythms of the banjo, would go on to become the bedrock of a distinctly American sound. As time passed the minstrel show phenomenon arose to artificially codify in popular culture of the day the much older natural interplay between the European and African-based collaborations that set the stage for much that followed.

Across the southeast the continuing black fiddle tradition had a formative influence on white fiddlers and string bands. By the late 19th century black urban communities, with their piano-based innovations, horns and woodwinds, started to command more popular interest and overshadow the older fiddle\banjo dance music. The newer blues form exerted an irresistible influence on all southern fiddling and the commercial genres that grew out of it.

“Take my old daddy. When he’s playing the fiddle in slavery time, he wouldn’t want to play, but he had to play!” —Sam Chatmon

Jefferson Davis “Dave” Dillingham was born 1866 in Florence (then Brooksville) Texas. He moved with his parents Bruce and Sarah to Georgetown when he was six-years old, and later a few miles up to Merrilltown, now extinct. Dave started work as a freighter with his brother Brice, driving four mules and an ox team between Austin and Brownwood, then farming and eventually working as a brakeman on the narrow gauge A&NW railroad between Austin and Granite Mountain, west of Marble Falls.

“Here a tribute must be paid to a very humble individual of Williamson County, of the Florence neighborhood…an old Negro named Wash Hubbard who could play the banjo like it was part of his body…. Dave first heard Wash Hubbard play that old banjo when he was a mere boy. On the instant he was wild to learn to play but he had no money and could not buy a banjo. Finally he found an old gourd. He stretched a piece of hide across it…and fashioned strings from a horse’s tail. He listened to old Wash on every dance occasion and it is said that at some times his nose got into the way of Wash’s banjo strings. He learned nearly all the old tunes from Wash Hubbard, like “Green Corn,” “Turkey in the Straw”, “Arkansas Traveler,” and “Buffalo Gals…”

—Jefferon Davis Dillingham as quoted by T.U. Taylor, Frontier Times May 1937

The interplay between black and white musicians, while largely undocumented, can certainly be viewed as yet another exploitative appropriation on the part of the ascendant power structure. But I would offer and feel that it is justified to hope that the relations out of which so much beautiful music has come were at times more humane, personal, genuine and ordinary, in as much as it was possible under the oppressive regime in place at the time.

“Ten miles, as the crow flies, from McDade, Pat Earhart, a noted fiddler, lived. In June 1877, a dance was scheduled at Pat Earhart’s home. It was known that the suspects would attend the dance, and the prediction was verified. The Blue Branch Guards were organized and laid their plans with deliberation and care. Pat Earhart wielded his fiddle bow part of the time, but most of the time a Negro, Steve Hawkins, did the fiddling and called the figures.”

—In and Around Old McDade, T.U. Taylor Frontier Times Vol 16-No 7 May 1939

But what did it sound like? It is possible to speak exhaustively about relatively well-documented traditions like Round Peak fiddling, Bluegrass or Cajun music, but what if, contrary to fact, no recordings existed to inform us about these? Could we conjure up anything at all meaningful about the “High Lonesome Sound” or “fais do-do” if these forms had come and gone and left no audible record? Words alone can convey almost nothing about the music itself.

The recordings of Teodar Jackson have much to teach us about the sound of African American Music in its own right, not through the lens of commercial product but on its own terms. The new music, the liberating phenomenon of the blues, might be tracked back to the crucible at Okeh, Gennett, or Victor studios, but its beginnings are more likely to have been found somewhere deep in the lost memory of country suppers in or near countless small, hidden, rural fortress communities. What was that music like?

Assumptions about what it might have sounded like are crosscut by the effects of location, time, place, and circumstance. There was African American fiddling in the Cumberland Plateau, the Missouri Ozarks, even Manhattan Island. Field recordings of noted fiddlers like Cuje Bertram in Kentucky or Bill Driver in Missouri are radically divergent examples of what we might expect to find. Sid Hemphill, recorded by Alan Lomax in 1942 and again in 1959 in Mississippi, Belton Sutherland & Clyde Maxwell, John Bishop, and Worth Long at Maxwell’s farm in Madison County, Mississippi. All provide a chance to listen back to the lost sound at the heart of the music that got us here. But how did the music sound in Texas?

‘Couldn’t put the saddle on’ –Sam Chatmon

In a previous issue for the Field Recorders Collective (fieldrecorder.org), I helped to document and publish the 1941 recordings of P. T. Bell, an early white settler and fiddler from Carrizo Springs, Texas who was recorded at the age of 76. Mr. Bell was a second generation Texan born in 1869. Characteristic of many southern whites, his family had emigrated from England in the 1600s, and followed the wave of migration into Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Alabama before coming to Texas. Mr. Bell was an old-time fiddler who learned from his father. Even after the advent of electricity, radio, and telecommunications, Mr. Bell maintained his skeptical derision with respect to these as impertinent annoyances which he adamantly chose to do without. Still to our ears his rendition of the tune “Ladies Fancy” is undeniably Scottish in both execution and effect. Yet, Mr. Bell had doubtless not been within 200 years of hearing any representation of fiddle styles from that distant, foreign country! How generational transmission alone was able to bring to modern ears evidence of this deep, fundamental connectedness that is both apparent and certain is almost inexplicable, at least in terms we can understand.

“There used to be some mighty good musicians among the old setters, but that is something like the old setters themselves, they are but few left.” —Peter Bell

Similarly, I would suggest that there is a remarkable affinity between the fiddling of James “Butch” Cage (1894–1975), from Mississippi, and that of Teodar Jackson, whose grandfather had come from Mississippi in the middle of the 19th century. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that both, though widely removed from one another in space and time, may share somewhat in a common regional style and possibly repertoire. There is no way to be sure, but Teodar Jackson’s rendition of Whoa Mule included in the selections on this album is distinct from the other commonly heard “Mule” tunes popular among old-time fiddlers across the South. There are countless variations on Whoa Mule Whoa, Johnson’s Old Grey Mule, and Flop-Eared Mule, none of which appear musically related to Mr. Jackson’s version of the tune. Among the similar versions I have been able to identify are those of Butch Cage and another fiddled by Bill Chitwood with the Georgia Yellow Hammers on a 1924 recording for the Brunswick label.

On August 9, 1927, in the Hotel Charlotte, 237 West Trade St., Charlotte, NC, The Georgia Yellow Hammers, consisting of Phil Reeve (guitar), Clyde Evans (guitar), Charles Ernest Moody (banjo/ukulele), Bud Landress (vocal introduction), and Andrew Baxter (fiddle) recorded G Rag. It is thought that Andrew Baxter took over the fiddling on that side so that Landress could perform the spoken introduction to the tune. As such, that recording is likely one of the earliest racially integrated recordings of southern string-band musicians. C. P. “Phil” Reeve, who was born in 1896, also came to be business manager of both the Georgia Yellow Hammers and the African American father-son duo, Andrew and Jim Baxter, who made five or six discs for Victor, 1927-1930. Might Baxter have provided Chitwood with the distinctive version of Whoa Mule the Yellow Hammers recorded?

The versions of the tune Whoa Mule as played by Teodar Jackson, Butch Cage, and the Georgia Yellow Hammers each seem to be musically related to the tune Whoa Mule, Couldn’t Put the Saddle On as recalled by Sam Chatmon who, along with his brothers Lonnie Chatmon and Bo Carter, was a member of the much loved Mississippi Sheiks. The fact that each instance of that tune seems to have some contextual connection to African American tradition, could hint at the possibility of evidence for a trans-regional repertoire shared among black musicians.

Remarkably, a version of Whoa Mule was also played by Texas fiddler, Elijah Cox (1842-1941), who was recorded by John Lomax in San Angelo at the age of 93 for the Library of Congress (AFS-547-A2). His parents, Jim and Kizzie Cox had lived in bondage near Memphis, Tennessee, but managed to escape to Quebec, Canada where Elijah was born in 1842. His early years were most likely spent in Michigan, a free state. Sometime after his military service with the 6th Illinois Cavalry he came to Texas and served on the Texas Frontier in the 25th Infantry starting in 1870. And that was just the beginning of his adventures! Mr. Cox was perhaps the oldest fiddle player ever recorded, black or white. The recording of his Whoa Mule bears hallmarks shared by Teodar Jackson’s version. As noted by Stephen Wade, the tune may echo Old Joe as played by Frank Patterson (fiddle) and Nathan Frazier (banjo), who were recorded at Nashville, Tennessee in 1942. (AFS-06679-B02).

Interestingly, there are recognizable similarities that tie this version of the tune to a Whoa Mule presently played in the modern Texas-Style fiddle tradition and associated with fiddlers like Major Franklin, Garland Gainer, Terry Morris and others!

“Not too fast.” –Teodar Jackson

Robert Shaw grew up on a 200-acre farm near Stafford, Texas. His parents, Jesse and Hettie Shaw provided for their family by raising cattle and hogs. They managed well. Their house had a Steinway grand piano, on which Robert’s sister practiced her lessons. Denied by his father, Robert nonetheless managed to “catch the musical strains” by crawling under the house during his sister’s lessons. Despite his father’s opposition, he was determined to become a musician and did so, with singular determination.

By the 1920s, he was a respected member of the itinerant sect of barrelhouse piano players who played the “Santa Fe Circuit”, named after the trains they hopped to make their gigs across East Texas, playing cotton picks, lumber camps, “chock houses” and bars as far distant as Chicago, Illinois. Shaw eventually settled down, married and ran a grocery store called the Stop and Swap on Austin’s east side. He was named Black Businessman of 1962 by the Austin Chamber of Commerce.

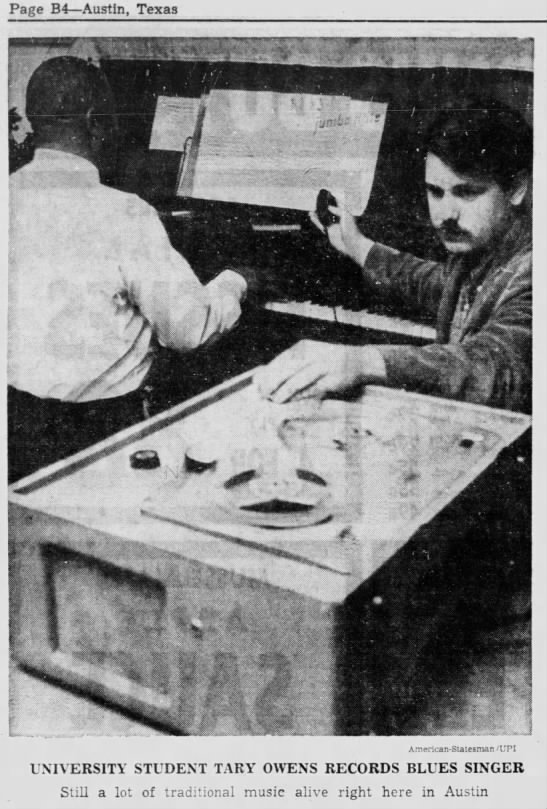

In 1965, Tary Owens was a student at the University of Texas. As part of his study under the renowned folklorist, Américo Paredes, Tary sought out Robert Shaw and helped to reintroduce Austin to his wonderful playing. It was Shaw who led Owens to record Teodar Jackson, accompanied by his son T. J. Jackson on guitar. In Teodar Jackson’s fiddling we have our best chance to listen back across time to the music of distant generations, to hear some of the signal concepts at the core of country fiddling, black and white, here in Texas.

Old sow’d whistle and the little pig’d dance

I’m gonna help, me and a ol’ tin pan

Yellow-gal-yellow-gal git up in the cool.

—Teodar Jackson

The fiddling of Teodar Jackson arguably includes some aboriginal versions of widely known early blues. Well known songs like See-See Rider and Hesitation Blues as well as less often encountered Texas songs like Jack O’Diamonds, Alley Blues, West Texas Blues and Blood Red Rose. His repertoire also included rags like Silver Spoons and fiddle tunes like The Chicken Reel and Drunken Hiccups. But in addition there are a few that are less readily classifiable, at least in modern terms. To hear Teodar and TJ play Old Aunt Jessie Get Up In the Cool is to really encounter something, perhaps for the first time. Free rein is given to Mr. Jackson with the fiddle moving through several charming parts unrestrained by rote periodicity while TJ holds the guitar to a steady gallop. The Rabbit (or Poor Rabbit) and Whoa Mule are similar, freely linear in structure. No “course part and fine part” in these tunes. It might be imagined that they harken back to an older, less restrained approach to the music, one that arguably could be seen as having something deeply in common with formal structures and improvisational techniques that can still be heard today in some traditional African music.

The beauty of this African-style fiddling from what Miss Suzie Piper had called “the rural” went largely unnoticed as it began to disappear even before the early years of the 20th century. The vitality of the old sound persisted, but only in corners. We may well hear echoes of the old dance tunes in some of the few commercial recordings of artists like Jim Booker who cut sides with Taylors’ Kentucky Boys, or Bill Broonzy who grew up fiddling in Arkansas. What of field recordings of noted musicians, Frank Patterson and John Lusk of Tennessee, or Butch Cage of Mississippi? All provide valuable insight, but none of these musicians were from Texas. With the exceptions of cowboy fiddler Jess Morris of Bartlett or Coley Jones’ Dallas Sting Band, there are almost no recorded examples of early African American fiddling from the state where the fiddle is supposed to be as iconic as the Lone Star itself. These recordings of Teodar Jackson then may provide our best chance to claim any real insight into the early sound of old-time African American fiddling in the Southwest.

“One of the largest and finest arrays of Texas folk and blues talent will be presented here Sunday in the form of a benefit concert for ailing Austin blues fiddler TEODAR JACKSON.” —Jim Langdon’s Nightbeat, Austin American Statesman, March 9, 1966

Coming out of retirement in 1965, Mr. Jackson was embraced by the young crowd at the heart of the nascent Austin music scene in the mid-1960s. Like his friend the Navasota songster Mance Lipscomb, he was idolized playing for many rapt, if largely white, audiences in venues like the Id Coffee House, where he was recorded by George Lyon. He and his son, TJ, were featured at the KHFI-FM Summer Music Festival in Zilker Park. According to Jim Langdon’s Nightbeat column in Austin American Statesman in 1966, Mr. Jackson was expected to be featured in the upcoming Newport Folk Festival up in Rhode Island. Unfortunately, a heart attack would intervene and send him off for a stay in the hospital instead. But for that lamentable setback, Teodar Jackson might now be as well known among folk music fans today as Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James, or Bukka White

Mr. Jackson’s condition began to worsen and on March 12, 1966 the community came together for a benefit concert. The event was well publicized and reportedly a resounding success. It was standing room only at the Methodist Student Center when many now familiar performers took the stage for Mr. Jackson’s benefit:

Janis Joplin was there to take the stage just before leaving to join the new band Big Brother and the Holding Company in San Francisco. Mr. Jackson’s old friend Mance Lipscomb shared the stage with the 13th Floor Elevators, John Clay, Bill Neely, Kenneth Threadgill, Johnny Moyer, Powell St. John, Allen Dameron, Lanny Wiggins and others. —Jim Langdon, Nightbeat

Janis Joplin started off with three songs: Going to Brownsville, I Ain’t Got to Worry, and Buffy St. Marie’s version of Cod’ine. She also sang Turtle Blues, an original that she admitted was “semi-autobiographical”, according to Jim Langdon. She then joined the 13th Floor Elevators and sang backup vocals for a set. Janis had played a previous Teodar Jackson benefit at The Eleventh Door in Austin, on March 5-6, 1966. The 13th Floor Elevators also played this event. The benefit shows for Teodar Jackson were formative events in the early Austin music scene. Arguably it was also, thanks to an over-head projector, Pyrex pie plate, vegetable oil and several bottles of liquid food-coloring, the very first occurrence of a psychedelic light show in human history.

Like the P. T. Bell recordings that similarly provide a singular example of Scots-Irish fiddling in Texas, the tapes of Teodar Jackson thankfully have been preserved here and made widely available by the Field Recorders Collective. These recordings present for perhaps the first time an opportunity for the general public to listen back across time and space to hear echoes of the actual music about which much has been conjectured but almost nothing really known: the sound of African Texas fiddling from, as Miss Suzie called it, “the rural”.

***

Acknowledgements:

John Wheat, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, Austin Texas

Carment Kiara, Carment Kiara Youth Organization

Joe Dobbs, University of Texas Libraries

Maryann Price, Musicia

George Lyons, Mount Royal College in Calgar

Christy Foster, Musician

Gary Lee Moore, Musician

Leo Sullivan, Producer, Sage

Robert Sacré, Charley Patton: Voice of the Mississippi Delta, University Press of Mississippi, 2018

Charles K. Wolfe, “The Georgia Yellow Hammers” in Classic Country: Legends of Country Music New York: Routledge, 2001.

Stefan Wirtz’ American Music, http://www.wirz.de/music/america.htm

Alan B. Govenar(editor), The Blues Come to Texas: Paul Oliver and Mack McCormick’s Unfinished Book, Texas A&M University Press, 201

Sharon Hill , The Empty Stairs: The Lost History of East Austin

Bonnie Tipton Wilson , Intersections: New Perspectives in Texas Public History, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Texas State University , Spring 2012).

Robert Winnans, “The Black Banjo-Playing Tradition in Virginia and West Virginia”, Journal of the Virginia Folklore Society 1(1979)

Susie Sansom-Piper, On the Other Side of the Tracks, SERIES: Saturday Nights Back in the Day, Rockdale Reporter – February 3, 2011, Interview 2014 Milam County Historical Commission

Marshall Wyatt of Old Hat Records, http://www.oldhatrecords.com

Dana J. Epstein, Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War,. University of Illinois Press, (1977, reissued 2003),

Tony Thomas, Why Black Folks Don’t Fiddle, http://bluegrasswest.com/ideas/why_black.htm

Paul F. Wells, Fiddling as an Avenue of Black-White Musical Interchange,

Black Music Research Journal Vol. 23, No. 1/2 (Spring – Autumn, 2003), pp. 135-147

Stephen Wade, The Beautiful Music All Around Us -Field Recordings and the American Experience, University of Illinois Press, 2012

Michelle M. Mears, And Grace Will Lead Me Home – African American Freedmen Communities of Austin Texas 1865-1928, Texas Tech University Press 2009

Jaqueline Gogdell Djedje – Fiddling in West Africa, Indiana University Press, 2008

The (Mis)Representation of African American Music: The Role of the Fiddle, Journal of the Society for American Music, Cambridge University Press, 2016

Noah Smithwick, Evolution of a State or Recollections of Old Texas Days, University of Texas Press, 1983

Margaret McKee and Fred Chisenhall, Beale Black and Blue: Life and Music on Black America’s Main Street, Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

Murray Montgomery, Texas Escapes Online Magazine, http://www.texasescapes.com

Weenie Campbell, http://weeniecampbell.com

Newspapers.com

Austin American Statesman

TheTexas60sMusicRefuge http://group.yahoo.com

TheGhetto (texasghetto.org)

PragueFrank’s Country Discography, http://countrydiscoghraphy2.blogspot.com

New Georgia Encyclopedia

True West Historical Society