FRC714 – Tom Fuller – Traditional Fiddling from Oklahoma & Texas

By Brad Leftwich

An earlier version of this article first appeared in The Old Time Herald, Volume 13, Number 11.

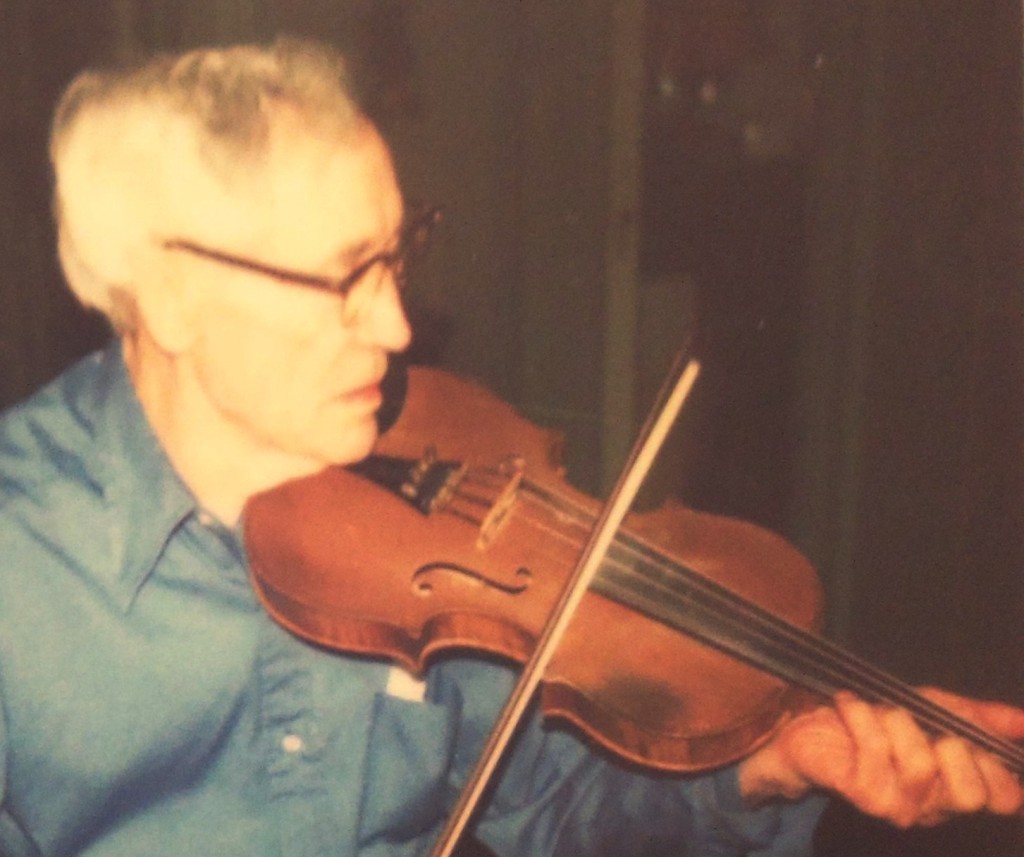

I stood in Jan Fitzgerald’s home recently in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, holding her father’s familiar old fiddle in my hands and trying to wrap my mind around the fact that it had been almost 40 years since I had last seen it or heard him play. Tom Fuller’s fiddle was just as I remembered: the top was painted brown, which he had done when he discovered he had no varnish in the house after a repair (I can still hear his voice: “Brad, I’m the kind of fellow who likes to get a job done one way or another”), and there was the old rosin-encrusted bow with enough of the finish worn away to reveal that it was made of aluminum.

Miraculously, the glue joints were still solid; the strings, bridge, and sound post were all there; and enough hair remained in the bow to hold rosin from the ancient cake that I found in the compartment of the case. I carefully tuned it up and then launched into one of his tunes: “Jan’s Tune,” he had called it, because it was his daughter’s favorite. It was an emotional moment. Jan’s daughter Cindy caught it on her cell phone camera and immediately emailed the video clip to me. I couldn’t help but be struck by the odd incongruity of that ultra-modern technology and the beat-up old fiddle. How vastly different must have been the world Tom Fuller was born into – 124 years earlier!

A hard start in life

Both sides of Tom’s family were from Missouri. His maternal grandfather, Aaron A. Baxter, was a Baptist circuit preacher who had moved with his family from Missouri to Texas around 1882. Tom’s father, Thomas Daniel Fuller, married Aaron’s daughter Emma around the same time. The new couple came to Texas also, most likely accompanying her family. Tom’s older siblings were all born in the Lone Star State.

Even as the Fullers started their own family, calamity befell the Baxters. Aaron’s descendants say he was murdered. The story that has been passed down in the Baxter family is that his horse returned one day without him, and he was found shot in the back, robbed of the church collection money.

The Fullers moved to Indian Territory about 1889. Tom was born November 20, 1890, and his parents named him Thomas Lonzo Fuller. He was the next-to-youngest of six children, and the first to be born in their new home in the Chickasaw Nation. They lived near what is now the town of Countyline, on the boundary between Stephens and Carter counties in southern Oklahoma.

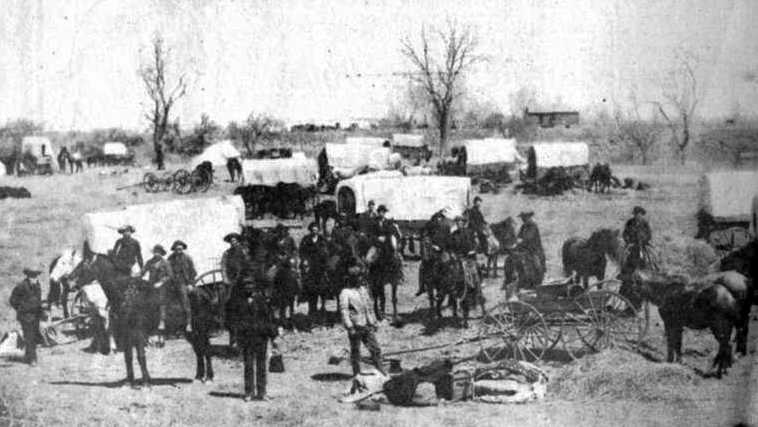

At that time there were actually two territories: Indian Territory, or I.T., was roughly the southeastern part of the present state, and Oklahoma Territory, or O.T., was the northwestern part. Big changes were afoot in Oklahoma Territory. Lands that had previously been held as reservations for various Native American nations were being opened to white settlement through a series of land runs. These were dramatic and colorful events in which throngs of people would mass along the border and, at the shot of a pistol on a given date and time, race in on horseback, in wagons, or on foot to claim land. Cities sprang up literally overnight.

Hopeful settlers begin gathering for the opening of the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation on April 19, 1892. Tom’s grandmother Elizabeth Baxter and her family made the run and successfully staked a claim. (Clinton Daily News Photo Archive, Clinton, Oklahoma).

When the Cheyenne and Arapaho reservation was opened in 1892, Elizabeth Baxter, Tom’s grandmother, recovering from her husband’s murder, packed up her children to start over again in Oklahoma Territory. On April 19, she and her family lined up with 25,000 other hopeful settlers. The starting gun was fired at noon, and they were among the fortunate ones who were able to stake a claim. They established a farm in Washita County near present-day Mountain View, not too far from her daughter and son-in-law.

Before long, misfortune struck again – this time in the Fuller family. Tom’s mother Emma died in 1896, when he was six years old, leaving his father struggling to care for their half-dozen children by himself. Just two years later, in Earlsboro, O.T., the father was involved in an altercation that concerned two of the girls.

The tragedy was still fresh in Tom’s memory when he related the story to his grandsons nearly three-quarters of a century later. According to Mike and Steve Fitzgerald, Tom’s father was a horse trader, an occupation that required him to be away from home for extended periods of time. It was necessary for him to place his children with other families during those times. Among those who helped out were a minister named William Cantwell and his wife, a couple who were unable to have children of their own.

On this occasion, Cantwell took in Tom and two of his sisters and, unbeknownst to their father, was determined to keep the girls. On the day Fuller was to return and collect his children, Cantwell concealed the girls in a wagon and left. Suspicious, Fuller returned later, unannounced and carrying a rifle, and confronted him. Cantwell retrieved his own rifle. As Tom watched, Fuller and Cantwell argued, gunfire broke out, and his father was fatally wounded. Young Tom became an orphan at the age of eight.

Tom and all of his siblings except for a married older sister went to live with their grandmother on the farm she homesteaded in Washita County. Tom lived there for two or three years (he appears as a member of the household in the 1900 census). She gave him a loving home, and ever afterwards he was especially fond of her.

Elizabeth raised at least eight children of her own. After the death of her husband and taking in her orphaned grandchildren, she became the head of quite a large household. To ease the strain, Tom went to live with his sister who, in a now-familiar pattern for the family, was already a widow herself with two small children. There was plenty for him to do, and he made himself useful.

Shortly thereafter, Tom met the girl who would become his wife. At the time, he was 12 years old and Abbie Gail Stearns was just 7. Tom and his older sister were traveling by wagon from western Oklahoma to visit family in Missouri. They had reached Boggy Creek when one of their horses died. Tom’s sister borrowed a horse from the Stearns family, and left Tom there – perhaps to guarantee the return of the horse. He turned out to be such a good worker around the farm that Abbie’s parents wanted to keep him, give him a good home, and send him to school. Before long, however, his sister sent for him. Tom and Abbie stayed in touch, sending letters back and forth.

As a young teenager, Tom went to live with his aunt and uncle, Nora Baxter and John D. Williams. They lived not far to the east of his grandmother’s place, on a farm near Fort Cobb in Caddo County. His uncle was the archetypal cowboy: tall, lean, and tough, with a big mustache and a strong work ethic. Williams became a role model for the fatherless boy and had a big influence in the molding of his character. He was very good to Tom, who always described him as “the man who raised me.” He taught Tom about horses and livestock, cowboy work and farming, and paid him for his work around the place.

Tom and his beloved horse Smoky that he raised himself. According to his children, there were tears in his eyes the day he had to sell Smoky to raise money so they could buy a car. It appears from the ribbons that Smoky has won some contests (courtesy Fuller family).

It was about this time that Tom began playing the fiddle. He taught himself to play by ear, and was active playing for dances in the area from his early teens through his early twenties.

He was eager to get out on his own, so when he was about 15 he took over a field from his uncle, “bached” in a shack by himself, and raised a crop. It was a hard life with few comforts. At night he rolled out a pallet; in fact he said he never slept in a bed before he was 21 years old. It’s not hard to imagine that playing the fiddle would have been welcome entertainment.

Because he had to work, Tom didn’t get as far in school as he would have liked. His wife Abbie told me he went to a country school near Fort Cobb and probably made it to seventh or eighth grade. Most of Tom’s classmates and friends at school were Native Americans, and he could speak some of their language.

By 1910 Tom was boarding with his older brother Willis, the two of them farming together on their uncle’s land near Fort Cobb. Tom had continued his correspondence with Abbie, once even managing to talk with her by telephone. He went to visit in person when he was 17. After that the tempo of the courtship accelerated, leading to their marriage in 1915. He was 25 years old and she was 19.

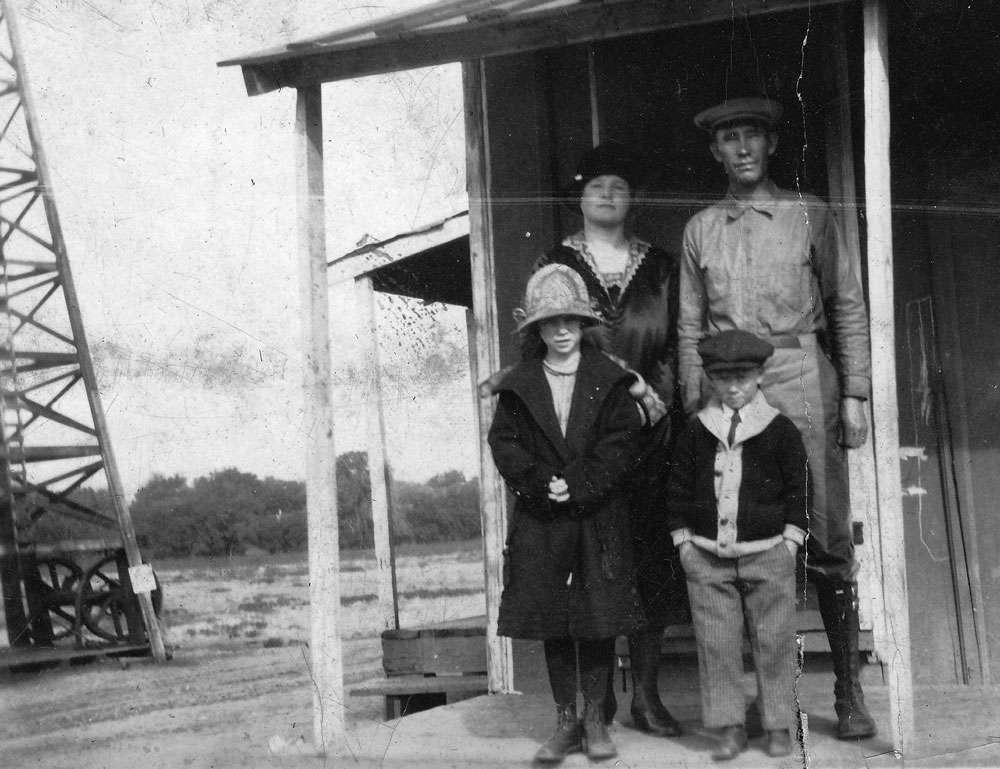

They settled initially in Cox’s Store, about 10 miles east of Lawton. Tom had a variety of jobs, doing cowboy work, farming, and hauling with a wagon and team. They moved several times: first to Lawton, where their oldest daughter, Loyce, was born in 1916; then west of Lawton where they rented a farm with a two-room house for about a year; then back to Cox’s Store where Tom sharecropped with his father-in-law. Their second child, Tommy, was born in 1920.

This was a hard time for the Fullers. Tom struggled to earn a living, and Loyce said they nearly starved to death on the farm. Family life and long hours of work left little time for music, and Tom played for fewer dances during this period.

Boom times

The Fullers’ luck began to change with the oil boom in Oklahoma and Texas. In 1921, oilfields were developed in the vicinity of nearby Duncan, Oklahoma, and in 1922 the family was able to leave the farm when Tom landed a job as a roustabout. He hired on initially with the Roxana Oil Company, a predecessor to Shell Oil, and then he worked for Shell for the rest of his career. The family moved frequently at first as Tom was transferred back and forth between Oil City and Gas City, two boomtowns near Duncan.

During the 1920s, the family moved several times as Tom was transferred back and forth between Oil City and Gas City, two boomtowns near Duncan, Oklahoma (courtesy Fuller family).

In 1929 Shell sent Tom to Kilgore, in east Texas, to work in newly opened oilfields there. Being a roustabout was a transient job, so the family remained in Duncan. Tom lived out of his car, but this was during the Great Depression and he felt lucky to have a job at all. In order to give more people jobs, Shell worked employees in alternating two-week shifts. Tom would drive back to Duncan during his time off. Their third child, Jan, was born there in 1930.

In 1932, Tom moved up to a more desirable job as a pumper, responsible for operating and maintaining the oil well pumps on the company’s lease. A year later, another pumper position opened up in McCamey, in the arid expanse of west Texas, and Tom was chosen to fill it. Because being a pumper was a stationary job, the Fullers were able to be together again as a family.

They took up residence in a shotgun house among the pump jacks on the Sapp oil lease about ten miles out of McCamey, in a valley between the low, flat-topped peaks of King Mountain and Castle Mountain. Soon they moved into the Shell Camp, comprising several houses for employees and a community hall where Tom played for dances. They relocated to another oil lease that was closer to town when Jan was in junior high, but they never left the McCamey area again until Tom retired. Their fourth child, Dan, was born there in 1937. They felt very prosperous, especially when Shell replaced their old shotgun house with a brand-new home with indoor plumbing and an actual bathroom.

Tom retired in 1953 after 30 years with Shell Oil. He loved horses and stock, and loved growing things, so after spending so many years in the arid countryside of west Texas, he and Abbie moved to the lush Ouachita Mountains of Polk County in western Arkansas. They bought a house and 52-acre farm in the community of Ink, near Mena. Tom farmed and even did some cowboy work right up to the age of 75. Then the couple moved into Mena, where they lived out their remaining years. Tom died on March 13, 1979, at the age of 88.

When Tom retired in 1953, he bought a 52-acre farm near the community of Ink, in Polk County, Arkansas. He farmed and raised livestock for the next 12 years (courtesy Fuller family).

Tom’s life as a musician

In his early teens, about 1905 or a little before, Tom sold bluing, a product used to whiten laundry, to earn extra money to buy his first fiddle. He taught himself to play by ear initially, watching and listening to other fiddlers in the area. He played quite a few dances as a teenager and into his early twenties. After marriage in 1915, he still played occasionally for dances, but not as often.

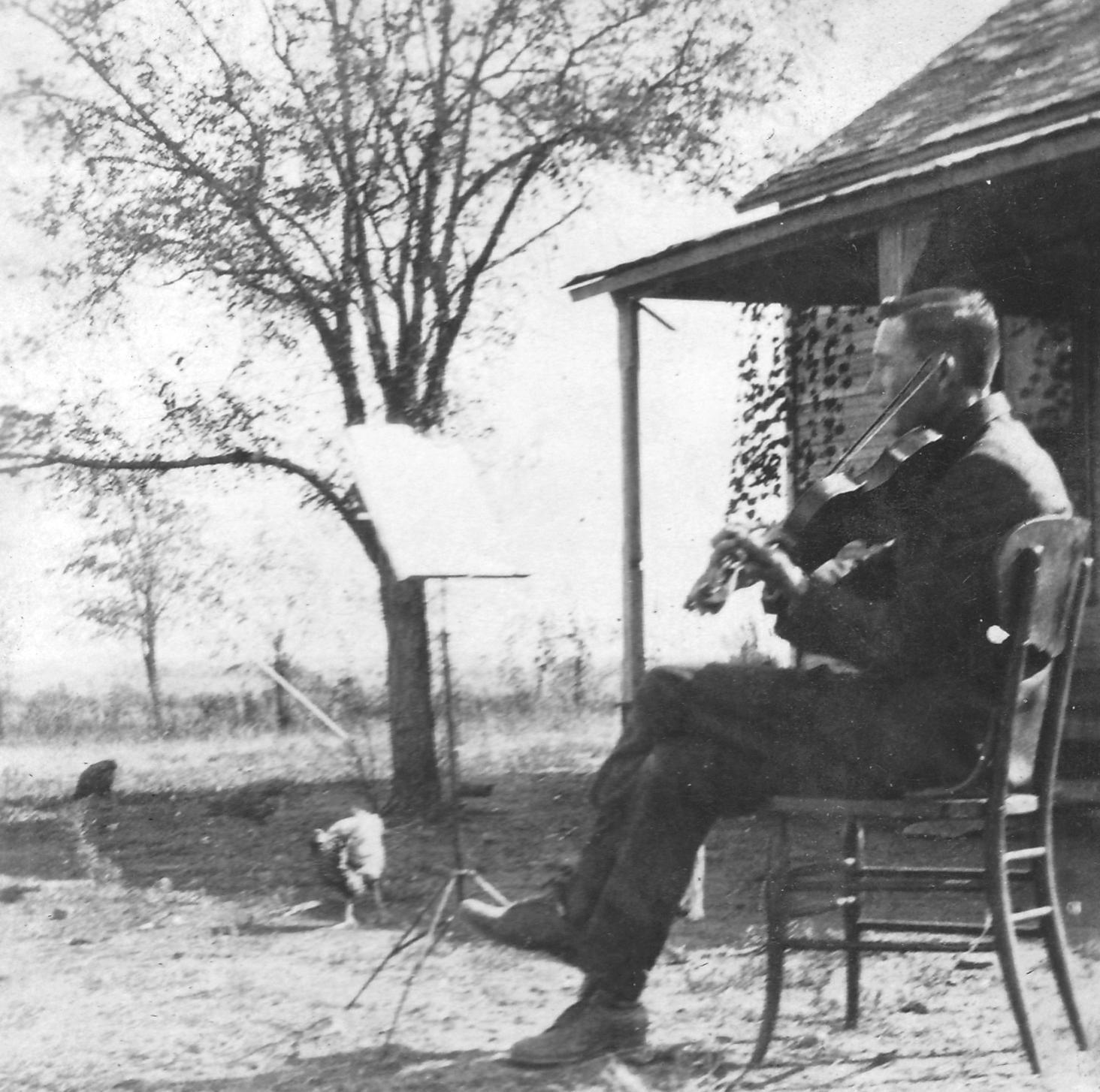

Eager to improve his skills, he took some lessons from a music teacher in Hulen, Oklahoma, in the early 1920s, before he and his family moved to Oil City. He was proud of learning to play “by note,” and afterwards he enjoyed playing music from the church hymnal. He used to joke that he played fiddle for dances and violin for church.

Tom initially taught himself to play by ear, but he was proud when he learned to play “by note” in the early 1920s. Note the music stand and the chickens (courtesy Fuller family).

In the early years of Tom and Abbie’s marriage, while they were still living in Oklahoma, there weren’t many other musicians with whom Tom could play on a regular basis. He didn’t have much spare time for music during that period of his life in any case. But on the occasions when he did play for a dance, a guitar or banjo player often seconded him.

With the move to McCamey, Texas, in 1933, Tom’s music once again began to flourish. There were more opportunities to make music, and more musicians with whom to play. And he didn’t have far to look for backup: when daughter Jan grew old enough, she began playing music with him. She was his main accompanist until 1947, when she left home to go to college in Denton.

Tom started Jan out on a small violin as a young girl. In the two-violin configuration they played mostly hymns, both at home and sometimes for Sunday evening services at the First Methodist Church. She says she nearly mastered one hoedown, which Tom dubbed “Jan’s Tune” in her honor. Jan remembers her father telling her, “When I’m gone, I want you to have my violin.” And she still has it to this day, along with the small violin he bought to get her started.

When Jan reached her early teens, Tom taught her to play guitar, and she began backing him up at dances. Playing for long dances on a steel-strung regular guitar was hard on her fingertips, however, so when she was in junior high school Tom bought her a lap steel guitar, which was played with a slide. Before long they bought a piano for $100 (which her son Steve still owns), and Jan learned to accompany fiddle tunes on it.

Tom depended on his daughter Jan for backup at dances until she left for college in 1947. They also enjoyed twin fiddling on hymns (courtesy Fuller family).

Dances were a popular form of entertainment in the 1930s and ’40s. Every month or so Tom played for parties sponsored by Shell Oil for its employees, joined by Jan when she was old enough to provide backup. The parties featured dancing as well as free beer, sodas, barbeque, and watermelon. Jan and her sister Loyce said people danced two-steps, waltzes, and polkas as well as square dances at these events.

Tom’s son Dan came along later, seven years younger than Jan. He picked up the steel guitar she left behind when she went to college, and he then began playing with his father. Dan remembers that the venues where they performed included VFW dances and the Holiness Church, where one of Tom’s musician friends was a member (the Fullers were lifelong Methodists).

A dance fiddler had to be versatile. Tom played plenty of traditional hoedowns and waltzes, as well as some schottisches and polkas, but he also kept up with trends in popular country music and eagerly learned anything new that appealed to him. Bob Wills was very big at that time, and Tom bought sheet music for some of his hit songs. His son Dan still has a box of Tom’s music that includes titles like Johnnie Lee Wills’ “Rag Mop,” Spade Cooley’s “Oklahoma Waltz,” Jack Guthrie’s “Oklahoma Hills” – even Cole Porter’s “Don’t Fence Me In” and Irving Berlin’s “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.” But he gave even the tunes he learned from sheet music a distinctive sound that was all his own.

Tom played other instruments as well. He learned to play French harp, mounting it in a holder around his neck and accompanying himself on guitar. There’s also a photo of him playing lap steel guitar.

Tom and Abbie’s older son Tommy married into the Tidwell family, a musical clan in nearby Midland, Texas, with whom Tom played music whenever he could. Tommy’s wife Oneida Tidwell played guitar and sang, her sister Etta Pearl and brother Bill also sang, and “Daddy” Tidwell played fiddle. In the early 1950s, Tom, with his son Dan on lap steel, went with the Tidwells to a studio in Midland and made a record. “San Antonio Rose” is on one side, and “Kelly Waltz” is on the other.

This was strictly for fun, though. Tom was satisfied with his job at Shell Oil and didn’t aspire to a career in music. However, he associated with musicians in McCamey who did.

He had an interesting connection with the famous Seals family. One of the musicians with whom he played regularly was Wayland Seals, a fellow Shell Oil employee who worked by day as a pipefitter in the oilfields and at night as a musician. Wayland was a talented guitar picker who had modest success in a rockabilly band that made commercial recordings as the Oil Patch Boys in the 1950s. You can hear two of their recordings, “Oil Patch Blues” and “When I’m gone” on YouTube:

Raised in a musical home, Wayland’s sons were even more successful. Dan Seals became a major country music star. His older brother Jimmy also achieved stardom in the soft rock duo Seals and Crofts, which had a number-one hit in 1972 with “Summer Breeze.”

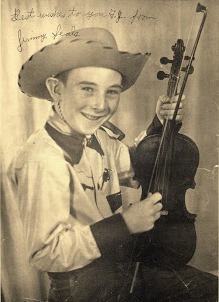

It’s a little-known fact that before hitting the big time in commercial music, Jimmy Seals was an old-time fiddle prodigy who won the Texas State Fiddle Contest in 1950 at the age of nine. He has been quoted as saying that he was inspired to take up fiddle after a group of his father’s friends dropped by one day after dinner to make music. Jimmy delighted in hearing the fiddler play, and asked for a fiddle of his own.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Tom and his son Dan Fuller played music regularly with coworker Wayland Seals and Wayland’s son Jimmy. Pictured here in an early promo photo, Jimmy became a Texas champion fiddler and later a rock star with Seals and Crofts (courtesy Tommy Castle).

It’s can’t be known for certain who the fiddler was who inspired Jimmy Seals to take his first step towards a career in music, but it’s intriguing to think that it could have been Tom Fuller. The families knew each other and played music together regularly. Dan Fuller, Tom’s son, was just a few years older than Jimmy Seals as they grew up together in McCamey and remembers him quite well. “He was about the best fiddler I ever heard,” Dan told me. “We played together, Dad and Jimmy on fiddles, Wayland on guitar, and me on lap steel.” So it’s clear that Jimmy played music with Tom and likely was influenced in some degree by his fiddling.

After retirement, Tom continued to play occasionally for dances at the community center in Ink, Arkansas. He loved to get together with other musicians when he had the opportunity, regardless of what they played. “Daddy played for his own pleasure,” said his daughter Jan, “and anyone who was interested in playing with him, it just thrilled him to death.”

My visits

I met Tom in 1971. I was 18 years old and he was 81. His grandson, Mike Fitzgerald, was a high-school friend of mine in Stillwater, Oklahoma. Mike’s birthday is January 8, and he told me that every year on his birthday the telephone would ring, and it would be “Pop” (as the grandkids called him) on the other end playing the fiddle tune “The Eighth of January.”

Mike knew I was learning to play banjo and was interested in fiddle music, so he invited me over to meet his grandparents when they were visiting during the Christmas holiday. Tom hadn’t brought his own fiddle, so I brought mine, which I was just starting to learn to play.

He played six tunes for me, which I recorded on the brand-new reel-to-reel tape recorder I had received as a Christmas present. I tried to play along on banjo, but I didn’t know his tunes and wasn’t accomplished enough to pick them up on the fly. In retrospect, I wish I hadn’t ruined the recordings with my poor attempts to second him.

Initially, I didn’t have enough experience to properly appreciate Tom’s fiddling. His fingers were bent with arthritis, especially the middle finger of his left hand, which sometimes caused him to play those notes flat. He claimed a 55 percent hearing loss, which made it difficult for him to correct pitch errors, and he was playing on my fiddle, which was set up differently than his own. I was fortunate to be hearing authentic traditional fiddle music from early twentieth-century Oklahoma and Texas, but to my novice ears it just sounded rough.

I put the tape away and didn’t listen to it again for another year. In the meantime, I had become more involved in old-time music and had the opportunity to hear a variety of other traditional fiddlers. The next time I got the tape out, Tom’s fiddling seemed much more interesting and listenable. There was an infectious, joyful lilt to his playing, and a distinctive sense of style in his bowing that was especially appealing. I decided to pay him a visit at home in the summer of 1973.

I drove to Mena, Arkansas, that August and spent a couple of days enjoying Tom and Abbie’s warm hospitality and making music. Tom was a gentle, good-natured man who smiled easily. He seemed always to have a twinkle in his eye and a playful comment to make. I found him thoroughly charming. He was delighted to have a visitor, and rarely left my side except to take naps or to go to sleep at night.

Tom loved to play with other people and didn’t seem to mind my inexperience or unfamiliarity with his tunes. He always wanted me to play along, and didn’t especially care to play solo for my tape recorder. “Get your banjo and play this one with me,” he’d say. I learned a lot on that visit, and continued to learn throughout the next year from the tapes I made.

I visited him again in July 1974 and made more recordings. I visited one last time in December 1975, bringing with me two musician friends, David Winston and Al Tharp. We didn’t have a tape recorder with us on that trip, unfortunately, although we had a wonderful time visiting and playing music.

That was the last time I made music with Tom. I heard from his family several years later that he had been out walking one day, and just lay down in the grass and passed away.

Some notes on the music

Tom thought of his tunes as being basically two kinds: on one hand were the old traditional hoedowns and waltzes, along with a few polkas and schottisches; and on the other, the commercial songs and tunes that he referred to as popular (or as he charmingly pronounced it, “poplar,” like the tree) music. He knew I was particularly interested in the hoedowns, so we’d play tunes like “Arkansas Traveler,” “Wagner,” and “Durang’s Hornpipe.” He enjoyed them, too, but he also really liked his popular tunes, so then we’d play some of his favorites, such as “Jambalaya,” “You’ve Got to See Your Mama Every Night,” and “Rubber Dolly.” He understood that those tunes and songs were hits way before my time, and that I didn’t quite understand their appeal; “You know,” he pointed out to me in his usual good-natured way, “there was a time when them pieces was very, very pop’lar.”

His playing was stronger on the first tape I made than it was later on, but my attempts to back him up are frankly embarrassing to me. In later visits my playing got somewhat better, but Tom was clearly slowing down. In the recordings, one hears the toll taken by his advancing age, hearing loss, and arthritis. He knew he was out of practice; he’d have to stop every now and then to take a nap and give his sore fingers a break, sometimes soaking them in rubbing alcohol. Once, winding up a music session, he touched my sleeve and said with a chuckle:

“That’ll be all for a while! Say, you know, you don’t know how much practice you’ve given me, your coming here, digging up [these old tunes]. Now some of ’em’s sort of hard for me to play again, you see. I used to just play them, really didn’t have to think of them, they’d just play their selves, seemed like. And now – playing things with you, practicing and everything, but still I find out – I’ve got to watch myself!”

But the careful listener will also hear the musical craftsmanship beneath the surface roughness: Tom’s intricate bowing with its bouncy lilt, his strong sense of phrasing, his distinctive arrangements of tunes, and his steady timing. He always stomped his foot when he played, and when he began a tune at a given tempo, that’s where it stayed!

He sometimes transposed tunes into different keys. Years after his death I discovered that I had recordings of him playing his distinctive “Great Big Taters in Sandy Land,” with its unique extra phrase in the high part, in both the keys of A and D. Although he didn’t say so, I’m pretty sure he played the one in D to accommodate me, because that’s where my banjo happened to be tuned at the time. Moreover, he told me he had originally learned it in the key of G. Similarly, I discovered I had one recording of him playing “Flop-Eared Mule” (a tune that switches keys between the two parts) in the keys of D and A, and another one in C and G. He moved “Buffalo Gals,” which fiddlers usually play in A or G, into the novel key of F just because he liked the sound of it. And I have to agree.

I wish I had thought to ask him about the sources of his tunes and the fiddlers he learned from, but I was young and more interested in learning tunes than history. He called one of his tunes “Demijohn,” which is the name of a creek west of Ardmore, not far from where he grew up, and it is doubtless among the earliest tunes he learned. “Jan’s Tune” is also known by the name “Oklahoma Run,” a reference to the land runs mentioned above that opened Native American lands to white settlement – one of which, the Cheyenne-Arapaho run of 1892, was an important event in his family’s history.

Although Tom played all his tunes in standard GDAE tuning during the time I knew him, he told me that in earlier years he had used a number of discord tunings, including DDAD, AEAE, and AEAC#. He stopped using them as musical tastes changed in favor of standard tuning with the growth of the commercial music industry, and he said his hearing loss later in life made it impractical for him to do much retuning in any case. Arthritis eventually caused him to simplify the left-hand noting on some of his tunes, but his bowing remained impressively complex.

He used many of the same bow rhythms that are found throughout the South, although there was something unique about his bowing that baffled me for years. At the time, of course, I was a beginning fiddler and everything baffled me. But eventually I began unraveling the techniques of my mentors and heroes such as Tommy Jarrell and Melvin Wine, and yet Tom Fuller’s sound continued to perplex me. What was the source of that jaunty bounce in his rhythm? Why couldn’t I duplicate it? Only recently have I begun to understand the unusual cross-bowing syncopation that was a staple of his rhythm.

Tom was eager to help me learn to fiddle and to show me his tunes, but he wasn’t particularly concerned that I play just like him. After one taping session he said,

“I hope that comes out plain to where if any of them you like, that you can copy off of them. And add to them if you can. If you find better bowing – and there’s always, you know how it is, if you study music – there’s always notes that will come in there if you know how to put them in; and if [they] come to you, let ’em in. Don’t try to copy me too close, because I’m not perfect.”

Coda

Abbie told me that although her husband was an orphan, he got lots of love while he was growing up. You could see it in his personality. And the love he had received, he passed along generously to others. Tom was a kind, nurturing man who loved growing things, loved raising animals, loved making music with other people, and above all, demonstrated his love for his family.

Jan likes to tell a characteristic story about her father. Shell Oil employees who had worked for the company for 25 years received an award. They could choose among different items of jewelry such as a tie pin or watch. When Tom hit this milestone, he chose a gold watch with two diamonds – a woman’s watch. He gave it to Abbie, and she proudly wore it the rest of her life.

I’ll always treasure the time I spent with Tom. In addition to his being a delightful person, it was a rare opportunity for me to be exposed to a traditional art that has all but ceased to exist. There’s plenty of great fiddling in Oklahoma and Texas today, but in the ensuing generations it has become a very different thing than it was when he was young. The recordings I made have now been released on the Field Recorders Collective CD FRC714, Tom Fuller – Traditional Fiddling From Oklahoma and Texas. I hope that even with all the recordings’ imperfections, they will help people to better understand and appreciate the history of fiddling from that area, and the artistry of Tom Fuller in particular.

© 2015 Brad Leftwich. Used by permission of Brad Leftwich and The Old-Time Herald