By Andy Cahan

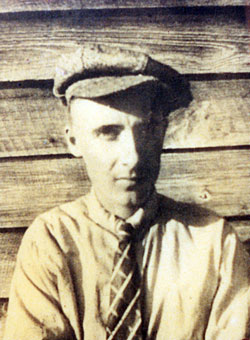

Walter Raleigh Babson was among the few banjo and fiddle players from coastal North Carolina still living in the late twentieth century. Originally from Ash, in Brunswick County, he lived at Wrightsville Beach for about the last 25 years of his life. He worked for many years as a carpenter and was a skilled woodworker as well. In earlier times he worked in various trades and occupations around Ash and Wilmington.

Walter Babson’s musical personality was unique. It reflected the influence of several streams and styles, and as a whole, was not the product of a regional tradition. His banjo playing had a highly developed sense of dynamics  and accentuation of rhythm and melody, and contained dramatic visual elements―tricks in which strings were plucked in unorthodox ways, graceful, exaggerated hand movements, and percussive taps on the banjo head. His repertory included waltzes, hymns, turn-of-the-century popular songs, minstrel songs, blues, dance tunes, and any melody that he found interesting and worth experimenting with.

and accentuation of rhythm and melody, and contained dramatic visual elements―tricks in which strings were plucked in unorthodox ways, graceful, exaggerated hand movements, and percussive taps on the banjo head. His repertory included waltzes, hymns, turn-of-the-century popular songs, minstrel songs, blues, dance tunes, and any melody that he found interesting and worth experimenting with.

Walter’s banjo technique encompassed so many components that an attempt to classify it would do it little justice. In the most basic terms, he used two distinct styles: the frailing, or down-picking style, which he vaguely referred to as “strumming”, and several forms of finger picking. During my visits with him from 1979 to 1987 he used the following tunings for both styles: GDGBD; GCGBD; and AGADE.

FRAILING

Walter’s frailing technique was driving and extroverted. Rhythm was emphasized through dense use of brush-strokes and fifth-string plucking. His prime concern, however, was the melody of a tune. During a conversation about Grandpa Jones, Walter made the following point: “His tunes are mostly chords-if he wasn’t singing, you wouldn’t hardly know what he was picking. My desire, always, was to carry out the pure tune if I could.”

Walter’s frailing did not employ double thumbing; his thumb plucked the fifth string only. He did, however use unorthodox techniques for adding notes. In Hesitating Blues, for instance, his left hand picked the melody while the right hand danced over the banjo neck, lightly brushing the strings. Such devices were fascinating to watch.

Another unusual embellishment was his finger tapping on the banjo head. He also developed an elaborate form of knuckle tapping, which he would do as a performance in itself. Using the knuckles and heel of one hand, Walter would tap out elaborate, syncopated rhythms on any available hard, resonant surface. He worked out this skill on his own, while still a young boy, rapping on a wooden matchbox while his brother danced.

FINGER PICKING

Walter’s finger picking took several forms, and could be classified as follows: three finger roll: used to play tunes such as Listen To The Mockingbird, Alabama Jubilee, Little Brown Jug, When The Roll Is Called Up Yonder, and Hello Coon (which he also frailed). Within this style the melody is found in an elaborate, rolling series of note patterns, reminiscent of the “forward roll” within Scruggs style banjo playing. In ways, his playing contained characteristics found in the style of Charlie Poole.

In playing tunes such as When He Sets Your Fields On Fire, Casey Jones, and Golden Slippers, Walter employed what could be referred to as double string harmonies. Here the emphasis is on melody, adorned with harmony notes rather than rhythmic patterns. His inspiration for this was harmony singing. He noted “I try and carry it through different (vocal) parts.”

Walter also occasionally employed a simple two-finger thumb-lead pattern. These style descriptions are merely basic outlines of a banjo music that was complex and texturally variable, and would often be combined within a tune. His varied renditions and their experimental nature were in large part due to the absence of a significant banjo tradition in the area in which he grew up.

PARENTS AND CHILDHOOD

Walter was the son of Mike Babson (b.1880) and Minnie Jane Babson (b.1881). Mike Babson’s great-grandfather had migrated to Brunswick County during the mid-nineteenth century from Gloucester, Massachusetts. Mike was a versatile man who ran a sawmill, ground corn, repaired machinery and automobiles, made pine tar, and all the while maintained the family farm. Until the depression years, Mike’s labors were fruitful. The family was somewhat more financially comfortable than most in the community, and was among the first in the area to own a car. Home life was characterized by an open-minded temperament. Walter recalled: “I have seen my daddy and mother feed the democrat and republican candidates together at our table at our own dining room, the day before the election. My mother was a democrat and my dad was a republican. There was no cross in the family; nobody said a word.”

Walter was the son of Mike Babson (b.1880) and Minnie Jane Babson (b.1881). Mike Babson’s great-grandfather had migrated to Brunswick County during the mid-nineteenth century from Gloucester, Massachusetts. Mike was a versatile man who ran a sawmill, ground corn, repaired machinery and automobiles, made pine tar, and all the while maintained the family farm. Until the depression years, Mike’s labors were fruitful. The family was somewhat more financially comfortable than most in the community, and was among the first in the area to own a car. Home life was characterized by an open-minded temperament. Walter recalled: “I have seen my daddy and mother feed the democrat and republican candidates together at our table at our own dining room, the day before the election. My mother was a democrat and my dad was a republican. There was no cross in the family; nobody said a word.”

Mike Babson was a banjo player, and his brother Whitt and a cousin Charles were both fiddlers. Another brother, John called square dances. Walter and his siblings were brought to these dances regularly. It was recalled that the local community largely frowned upon music and dancing, as many felt it to be sacrilegious. Walter recalled that to his knowledge, his family was the only one in the lower end of Brunswick County to have had a banjo. Yet despite this scarcity of other musicians, Walter felt that his father’s music was not a significant influence on his own. He described Mike’s playing as having been an informal, occasional pastime: “He’d come in from work and clean up and get his supper and maybe sit down and pick that thing up and just beat on it a little bit and lay it down. And that’d be it. That’s all there was to it. He’d just use it more or less for something to reconcile when he’d come in from work.”

Walter felt that his own playing reflected nothing of his father’s, neither in style nor in repertory. When asked whether he could play in Mike’s style, he went through a two fingerpicking pattern that used the thumb for the melody while the index finger alternated with it for rhythm. The style was reminiscent of two-finger styles used by mountain players such as Dan Tate of Fancy Gap, Virginia. Walter indicated his feeling that the style was repetitious and perhaps too monotonous for his taste.

MOTHER’S SINGING

MOTHER’S SINGING

Many of the songs in Walter’s repertory were learned from his mother, who was remembered as a fine singer. Walter’s sister Onnie Green (b.1913) recalled: “…she sang all the time. One of the sweetest memories that I have of my mother and daddy: we lived in the country-had a wood stove in the kitchen…Mama’d get up, put a fire in the stove, get that breakfast a’goin. And she was humming all the time that was going on. And Daddy would get up…and he’d keep a fire in that stove. Mama would sing. And he’d hit that bass (part). And we kids were lying in the bed and that’s what we woke up to most of the mornings. And when Mama sand What A Friend We Have In Jesus you didn’t lay there long, you got up!” Minnie Jane was also remembered as singing most of the hymns the children learned, as well as sentimental songs such as Silver Haired Daddy Of Mine, The Faded Picture On The Wall, When You And I Were Young Maggie, and After The Ball.

Walter estimated that his musical involvement began around the age of three or four. His father would leave his banjo, always in tune, on a table, and would instruct Walter not to pick it up. Wishing not to disobey his father, but longing to play the instrument, he would pull a chair up to the table and try to pick out melodies without moving the banjo. The Old Armchair was the first tune he worked out. In later years Walter would always preface this song by telling the story of how he learned to play it―complete with an imitation of himself as he sounded back then.

FIDDLING

Walter also developed an interest in the fiddle while a boy. This was sparked by the fiddling of his great-uncle Charles, but like his feelings about the banjo playing of his father, Walter credited Charles’ fiddling with little stylistic influence on his own.

“Great-uncle would come over once a week and play that violin he had. And I didn’t know nothing how to pick. Well, he played that thing and I’d hear it, you know. Well, I got after Dad and Mother about it. Seemed like I was interested in music. Well, they decided to send me to a music school. But it cost so much. And they didn’t have the money to back it up, so they didn’t. But he bought me a violin. He ordered one from some outfit in Chicago…it was guaranteed to be 150 years old. I’ve always had some kind of knowledge for music and never did know how. Never knew no music (notation). I knew the notes (from church singing) but that’s about it. And what I can do, I picked up from within myself.”

“Great-uncle would come over once a week and play that violin he had. And I didn’t know nothing how to pick. Well, he played that thing and I’d hear it, you know. Well, I got after Dad and Mother about it. Seemed like I was interested in music. Well, they decided to send me to a music school. But it cost so much. And they didn’t have the money to back it up, so they didn’t. But he bought me a violin. He ordered one from some outfit in Chicago…it was guaranteed to be 150 years old. I’ve always had some kind of knowledge for music and never did know how. Never knew no music (notation). I knew the notes (from church singing) but that’s about it. And what I can do, I picked up from within myself.”

BECOMING A MUSICIAN

In examining the formative years of Walter Babson’s musical personality, one sees a set of circumstances and events that were unusual if not paradoxical: on his father’s side of the family was a line of presumably traditional banjo and fiddle players.

His mother provided constant exposure to popular songs of the turn of the century, older traditional songs, and sacred songs. Given the local condemnation of instrumental music, the Babsons were isolated in their fiddle and banjo music. In the face of this, Walter was encouraged to develop his talents not by confining himself to the music within the household, but to look outward―beyond the family and local community to a music school where he would have received formal training. While this aspiration never came to fruition, the values and sentiments behind it may have had much to do with the originality and stylistic breadth that would come to characterize Walter’s banjo music.

MATTHEW LONG

Feeling that there could be more to banjo music than the simple style of his father, he began to absorb what he could from players he occasionally met outside the community, often incorporating songs and tunes not usually associated with the banjo. A significant musical influence outside of the family was a banjo player named Matthew Long. A Civil War veteran, Long was born in 1847, and lived in Lockwoodsfolly Township. Census reports reveal that Long and his parents had been native to the area, and were primarily farmers. He was the first player whom Walter heard play in the down-picking, or frailing style. “He had a stroke like that: (demonstrates frailing stroke), but more or less with his fingers balled up. Well, I kept watching him. And I think to myself, well, that’s all right. But a little more could be added to it. And I kept messing with it.” Long appears to have been something of a showman, as well as a fine musician. The theatrical, dramatic nature of his playing attracted Walter’s interest. He recalled: “Mr. Long, who came through the community every now and then, that’s where I got the desire to do something about it. He was pretty good, no doubt about it, and he was a good singer. That’s where The Preacher and The Bear come in at…he could also growl like a dog or a bear.” Long would also entertain with magic tricks: “He’d reach up and get money out of your ear, you know.”

SHADE BULLARD

Another of Walter’s varied musical sources was the singing of one of his father’s hired hands: “Back when I was just a little old bitty feller there was a young man that stayed with us and worked with my daddy. And that’s where I learned that tune. His name was Shade Bullard. He didn’t play a thing, he just sang it.” The tune was Hello Coon. Walter worked out finger picking and down picking versions of it.

SCHOOL BREAKINGS

In many rural areas of the south, before the consolidation of schools, ceremonies known as “school breakings” were common. The school breaking was an organized event that commemorated the end of the school year. Within it, students, teachers, and community members would give speeches, perform skits and marches, and play music. The music played was of the nature of hymns and other pieces that were appropriate for the situation, as dance music would not have been permitted at school.

Walter recalled: “On the school breaking nights I was one of them that was going to pull the curtain. And there come a man and his three sisters. He had come with his fiddle, and one of them had a mandolin, and two of them had guitars. And could they play music…the teacher said to me, “now listen: when they start that music don’t you be a-peeping through that curtain. Don’t you pull that thing back and peep.” Now then, when he struck that violin and them guitars there…there wasn’t no way…I pulled that curtain back a little bit and looked right down there, and she got me by the neck!”

CRUSOE ISLAND

Walter was also exposed to music on Crusoe Island, a small local settlement of primarily French ancestry. During regular contact with people there, Walter had the opportunity to learn several tunes. “Now you talk about guitar players and singers-they’re in there. Kind of like the Hawaiian Islands-they’ve got their music in there. And they’ve got their speech too, their language. Back then I was living down there. Before I came down here (Wrightsville Beach) I lived about five miles from there and I very well knew every one of them. And at that time there was right much bootlegging going on in there. And a stranger go on in there, they’ve got their eye on him right now. If you wanted to go in there you got someone they knew good and well (to) go with you and you’re all right. And they’d get their guitars together there and their singing and all that. They could really do it.”

NEW TECHNOLOGY

Traveling tent shows were a musical source. New technological advances played their part as well. Walter learned several tunes at a local silent-movie house: “(The movie) cost me 10 cents to see it. I was pretty good in them days at catching a tune. If I could hear it, I’d catch it.”

The phonograph played a significant role. It was during Walter’s generation that recordings influenced the repertories and styles of rural musicians for the first time. In the early 1900s Walter’s father purchased a brand new Edison cylinder record player, and was ordering records by mail. Although the phonograph drew the same criticism from the local religious community, Walter recalled that his family enjoyed listening to the early records and that it was a source of music for him to learn. Although he did not remember specific songs he learned directly from these records, one of the cylinders (or “cup records” as Walter called them) contained a song recorded for Edison in the early 1900s performed by vaudeville singer Billy Murray. There Must Be Little Cupids In The Briny was a comical song about a dandy picking up girls at the beach. Walter’s uncle Dave learned it from the record, and later Walter learned it from him. His rendition of the song is a beautiful example of the type of transformation that can take place when songs are learned by ear, and passed from one individual to another.

MUSICAL OUTLETS

Given the attitudes toward music around Walter Babson’s home community, one might wonder what sort of musical outlets existed during his boyhood. They were, in fact, primarily confined to the home, and to occasional gatherings which Walter called “country parties”, in which dances would be held. In these dances, “eight handed sets were the big deal.” Onnie Green described such gatherings that she attended as a child:

“Luther Ward (of another community in Brunswick County) loved that string music. And every once in a while, maybe every month or two, he’d tell Buddy (Walter) and them, “Miss Edna’s cooking up a bunch of fried chicken tonight. How about you boys coming to my house?” Well, they would go and I’d have to go with them. Mama would go, so we’d have to go. And Miss Ward would have a big supper. And after supper, Lloyd and Buddy would play, and my Mama would sing with them. And maybe it’d be 12, 1 o’clock before we’d leave from there. Mr. Ward’s neighbors would come and there’d be a house full, you know, there to hear ‘em.”

Walter Babson’s repertory and style were reflections of the varied situations and sources that were available to a musically inclined individual growing up in coastal North Carolina during the early 1900s. Having grown up in an open-minded family and not constrained by local tradition, he incorporated whatever struck him as beautiful, appealing, or simply fun to play. Driven by musical yearnings and innate creativity, he developed a unique musical personality that fortunately will now be heard by a larger audience.