The Dixie Hummingbirds (FRC208)

by Jerry Zolten

Author, Great God A’Mighty! The Dixie Hummingbirds: Celebrating the Rise of Soul Gospel Music.

Oxford University Press

No group is more revered in the history of black gospel than the Dixie Hummingbirds. With a career spanning 75 years, the Birds truly embody the changes that defined the genre as it evolved across the decades of the 20th Century. From a cappella spirituals to guitar-driven gospel to mainstream pop – the Dixie Hummingbirds have always operated at the leading edge of the curve and were masters of it all.

The Hummingbirds story begins in the early 1920s in the segregated town of Greenville, South Carolina. There, the young James Davis along with friend Barney Parks and a revolving line-up of schoolboy chums began singing in a quartet based at the Bethel Church of God Holiness located in the “Meadow Bottoms” section of town. In time, they built up a modest reputation, leading to invitations to sing at other churches, and eventually, a chance to sing at the annual Church of God Holiness national convention in Atlanta, Georgia They were a sensation, and the rousing reception from the audience inspired them to try and make a go as professional singers.

The Hummingbirds story begins in the early 1920s in the segregated town of Greenville, South Carolina. There, the young James Davis along with friend Barney Parks and a revolving line-up of schoolboy chums began singing in a quartet based at the Bethel Church of God Holiness located in the “Meadow Bottoms” section of town. In time, they built up a modest reputation, leading to invitations to sing at other churches, and eventually, a chance to sing at the annual Church of God Holiness national convention in Atlanta, Georgia They were a sensation, and the rousing reception from the audience inspired them to try and make a go as professional singers.

In 1928, after a few years of singing as the Sterling High School Quartet, the group – James Davis, lead, Barney Parks, baritone, Bonnie Gipson, Jr., second lead, and Fred Owens, bass ュ officially christened themselves the Dixie Hummingbirds. “It was the only bird that could fly both backwards and forwards,” James Davis would tell people over the years, “and that was the way our career seemed to be going at the time.”

For the next decade, the Birds embarked upon a campaign of what they called “wildcatting,” traveling from town to town, stopping at small radio stations, talking their way onto the air, and staying in the surrounding area until everyone knew the group by name. Then, they would move on to the next town and start again.

By 1938, they were hungry to kick their career up a notch. Gibson and Owens were no longer in the line-up, their replacements ? lead Wilson “Highpockets” Baker and bass Jimmy Bryant. Bryant was an established “star,” having previously recorded numerous sides for Victor records as one of the nationally renowned Heavenly Gospel Singers. Bryant took the Hummingbirds to New York City where in the fall of 1939, they laid down 16 a cappella spiritual tracks for the prestigious Decca label. If there was money made, none found its way into the hands of the Dixie Hummingbirds. “Prestige” was the sum total of their earnings. As the decade rolled over into the 1940s, they found themselves back in South Carolina – albeit with records to sell ュ but still wildcatting from country church to church with no solid prospects for the future.

That situation would soon change, initially through the addition of a new lead baritone, Ira Tucker, a versatile fireball of a singer from nearby Spartanburg, South Carolina. Tucker had been singing all his life, remembered by many in the community as the “little boy” who went knocking door-to-door offering to sing in exchange for a penny or two. As a child, Tucker, because he didn’t have the quarter admission fee, would climb trees that looked down into the church and listen to his favorites, the Dixie Hummingbirds, as their vocal music wafted out onto the night air. Now, in 1939 at age thirteen, Ira Tucker would leave his own quartet, the Royal Lights, and join the Dixie Hummingbirds, remaining with them over the course of a career which saw him emerge as one of the great lead singers in all of black gospel.

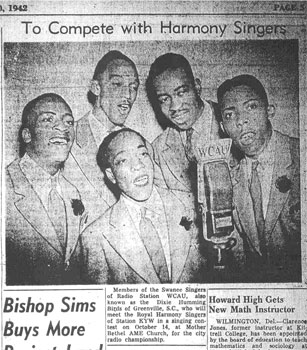

The next step in the rise of the Dixie Hummingbirds came in 1942 with a move north to the city of Philadelphia. The Birds moved to Philadelphia to take a regular singing job over one of the city’s most popular radio stations, WCAU. Station management, thinking the Dixie  Hummingbirds’ name too “black” for the station’s broad listenership, billed them on-air as the Swanee Singers. Their broadcasting success precipitated interest from legendary New York City producer John Hammond, who auditioned them as a foil to the Golden Gate Quartet, then regulars at the two locations of Café Society, the city’s first integrated night club featuring all-black entertainment. In 1943, the Dixie Hummingbirds, their name changed once again, this time by Hammond, to the Jericho Quintet, began a six-month run at Café Society. Here, with backing by the Lester Young Band, the Birds would perfect their showmanship, choreography, and stage presence.

Hummingbirds’ name too “black” for the station’s broad listenership, billed them on-air as the Swanee Singers. Their broadcasting success precipitated interest from legendary New York City producer John Hammond, who auditioned them as a foil to the Golden Gate Quartet, then regulars at the two locations of Café Society, the city’s first integrated night club featuring all-black entertainment. In 1943, the Dixie Hummingbirds, their name changed once again, this time by Hammond, to the Jericho Quintet, began a six-month run at Café Society. Here, with backing by the Lester Young Band, the Birds would perfect their showmanship, choreography, and stage presence.

Unfortunately, while at Cafe Society, the wartime draft began to decimate the Hummingbirds line-up. Of all the replacement singers that came into the group during this period, none would be more of an asset to the Birds than William Bobo, a friend of Tucker’s from Spartanburg and a bass singer blessed with one of the most profound voices in the genre. Surprisingly, John Hammond did not care for the new bass singer and replaced the Hummingbirds in Caf? Society’s revolving roster of talent. By 1944, the newly reconstituted group ュ James Davis, Ira Tucker, William Bobo, and Beachey Thompson – was back in Philadelphia and pursuing other options on the gospel battlefront.

The most promising of these options proved to be recording. Post-war America was rife with upstart independent labels, small operations that specialized in the regional and ethnic music ignored for the most part by the major labels. The Dixie Hummingbirds would release tracks on a succession of some of the Northeast’s most important independents, labels like Regis/Manor in Newark, Bess Berman’s New York City-based Apollo, and Ivin Ballen’s Gotham, the imprint acquired from Sam Goody and relocated from New York to the Birds’ hometown of Philadelphia. The Hummingbirds had made strides on the Apollo label, but owner Bess Berman proved to be more controlling about how and what they recorded than the group preferred. They were especially put off by pressure from her to record secular material. Though Ivin Ballen’s Gotham label did not have quite the reputation or reach of Apollo, the Birds were attracted by Ballen’s willingness to allow them to record what and as they wished. In fact, Ballen took the young Ira Tucker under his wing and taught him studio and production techniques that would serve Tucker well as the Dixie Hummingbirds moved ahead into the post-war span of their career.

As the 1940s rolled over into the 1950s, the Dixie Hummingbirds would position themselves for a final push to fame, first with a brief sojourn on Columbia’s newly revived Okeh label and finally, with a move to Don Robey’s Houston-based Peacock label, where they would blaze a trail that established them once and for all as among the greatest quartets in gospel. Robey was an enigmatic figure in mid-20th Century American pop music. While he had a reputation for his “rough and tumble” ways – Little Richard claimed in his autobiography that Robey had once beat him up – the Birds found him easy and, in fact, inspiring to work with. It was Robey, with his insistence on using drums and electric instrumentation, who ultimately brought the soul sound out in gospel performances by the Dixie Hummingbirds and many other groups on the Peacock roster.

The brief period from the end of the war through the early 1950s was a golden age for gospel and an experimental time for the Dixie Hummingbirds as they struggled to solidify their sound and establish their place in the gospel pantheon. At the time, women like Clara Ward, the Davis Sisters, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Sally Martin, the Georgia Peach, and Mahalia Jackson ruled the gospel roost, although male quartets were on the ascendancy. The trend was also shifting from old-time a cappella spiritual standards to original compositions and performances propelled by the beat of drums and the spark of electric guitars and bass. The Birds were in the thick of it and engaged on every front.

The tracks collected herein are a sampling culled from a period between their initial 1939 Decca sessions and their earliest Peacock sides in 1952, a thirteen-year slice that richly illustrates the evolving sound of the Dixie Hummingbirds during this vital phase in their career.

The Birds recorded twelve sides for Decca in 1939, represented here by three classic spirituals, “Leaning On the Lord,” Wilson Baker in the lead, “Lord If I Go,” with alternating leads and the growling bass of Jimmy Bryant, and “What a Time,” James Davis “calling,” the group “responding” in a rhythmically urgent hum, the overall feel foreshadowing the sound that would become associated with doo-wop and soul almost two decades later.

Though the Decca sides were moderately successful, the Birds would not record again until 1944, and then with a reconstituted line-up – Davis, Tucker, Thompson, and Bobo – and on a fledgling regional label that had nowhere near the reach of the prestigious Decca operation. That label was Regis based in Newark, New Jersey, later to become Manor. The Birds released one record on their own and another with Sister Ernestine Washington, a leading gospel diva of the day. The records did well regionally, but failed to improve the Birds’  position in the burgeoning national market for gospel. The group was shopping for a label with the kind of reputation and distribution that could move them up just a little bit higher.

position in the burgeoning national market for gospel. The group was shopping for a label with the kind of reputation and distribution that could move them up just a little bit higher.

They signed on to Bess Berman’s Apollo label, an independent with national distribution and an established track record of hits in r&b, jazz, and gospel, in 1946, the same year that gospel’s soon-to-be leading light, Mahalia Jackson, also signed to the label. They would indeed be on their way as over the next three years they released eighteen sides on Apollo, seven of those a cappella masterpieces collected here.

Two traditional spirituals, “Wrestlin’ Jacob” b/w “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” were paired as the Dixie Hummingbirds’ fourth release on the label. Both were somber renditions that showcased tight mellow harmonies, the profundity of William Bobo’s bass voice, and Ira Tucker’s emotive and versatile qualities as a lead singer. “Nobody Knows” would eventually become a Hummingbirds standard. “Jesus I Love You,” “I’ll Forever Stand, and “Jesus Has Traveled This Road Before” were similarly cast, with high tenor James Davis shining through on “Jesus I Love You” and Tucker’s pleading lead guiding the group through the shifting tempos that characterize “Jesus Has Traveled” and “Guide My Mind.”

“The Holy Baby,” in 1948 one of the last Birds releases on Apollo, was an a cappella tour de force, an original Birds arrangement that combined two standards, “Go Where I Send Thee” and the Christmas hymn, “Last Month of the Year.” The performance glides along, a call-and-response driven by William Bobo’s lead bass before breaking tempo into an impossibly fast meter that blurs the lyric into a passing splash of pure sound. There is some conjecture that bass singer Providence Thomas substituted for William Bobo on this track, but both Ira Tucker and James Davis recall Bobo on the session.

The last Apollo releases on the Hummingbirds would come in January of 1949. By July, the group would release the first of fourteen solo sides and six more in collaboration with the Angelic Gospel Singers on the Gotham label, the principle imprint of Ballen Records in Philadelphia. While they were pressured to record secular for Apollo, Ivin Ballen’s credo was “be what you want to be,” and indeed the Birds did experiment on Gotham. They would make their first recordings with instrumental accompaniment, and Tucker would begin to step out from behind the mike and develop his skills as both a producer and arranger.

The initial 1949 Birds release on Gotham was “I’ll Be Satisfied,” an up-tempo a cappella spiritual led by Ira Tucker, b/w “Lord Come See About Me,” again Tucker in the lead, but with a remarkable ending to the song by William Bobo, who sings, “Come see about?,” stops dead, pulls in an audible deep breath, and plunges into the depth of his low range on the final word, “Me-e-e-e.” Tucker comes in behind, gently resolving the piece in a shimmering falsetto glissando.

The Birds also released two “covers” on Gotham, “Search Me Lord,” Tucker’s take on Brother Joe May’s recent debut – a Thomas Dorsey composition – on the Specialty label, and “Two Little Fishes and Five Loaves of Bread,” a gospel novelty made famous by and closely associated with Sister Rosetta Tharpe. As to the latter, the Birds had toured extensively with Sister Rosetta, and Ira Tucker had learned a lot from her. “Tucker’s my baby,” Sister Rosetta would say. “He sings just like me.” And indeed, “Two Little Fishes” would be his tribute to Tharpe, one of his most important vocal mentors.

Perhaps the most popular of the recordings cut by the Dixie Hummingbirds for Gotham were their collaborations with the Angelic Gospel Singers, a female ensemble from Philadelphia led by pianist/vocalist Margaret Allison. The Angelics had abruptly risen to national fame on the strength of their initial 1949 Gotham release, “Touch Me Lord Jesus.” The idea to record the two groups together originated with Otis Jackson, a longtime Birds friend and collaborator from Jacksonville, Florida, but now also resettled in Philadelphia.

The two tracks represented here – “I’m On My Way to Heaven Anyhow” b/w “Glory Glory Hallelujah” – were the last of three releases by the Birds/Angelics on Gotham. Both performances, characterized by Margaret Allison as “old church songs,” played on a vocal amalgamation of the two groups backed by drums, piano, and organ. Tucker is the featured lead on “I’m On My Way,” but “Glory Glory Hallelujah” throws a momentary spotlight on a number of voices from the ensemble, most notably, tenor Ernest James, who would move in and just as quickly out of the Birds’ line-up during this period. “He really was a nice fellow,” recalls James Davis, but “most everything we sang was too low for him to lead界rnest James was a good singer in his range, but we had to let him go,” adds Tucker, “He went to the Nightingales. He did better with the ‘Gales than he did with us.”

The artistic measure of the Birds on Gotham, both on their own and in collaboration with the Angelics, was attested to by an invitation to record from a label with major distribution. In 1951, Columbia records revived the Okeh imprint as an entrée into the growing market for R&B, blues, jazz, and gospel. Tempted by the prospect of a major label boost to their career, the Dixie Hummingbirds signed on for two releases, one on their own and a second with the Angelics. “Today” and “One Day” are the tracks they recorded with the Angelics for Okeh. The formula remained the same as with Gotham, although state-of-the-art studios gave the performances a fuller ethereal quality. More importantly, adding his voice to the Hummingbirds mix on these tracks is Paul Owens, an exceptional lead vocalist/arranger and veteran of several Philadelphia gospel groups, most notably, the Sensational Nightingales. Owens proved to be an excellent foil to Tucker, and their dual leads would help position the Hummingbirds for the label shift that would lastingly propel the group into the gospel big time.

Though Okeh Records had national distribution, the label seemed to put the bulk of its considerable support behind a growing secular catalog. The Birds found themselves signed to a powerhouse label, but going nowhere. In the first months of 1952, they would make the jump to Peacock Records, a Houston, Texas label already starting to make noise in the business with secular artist Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown and gospel quartets the Bells of Joy and the Mississippi Blind Boys featuring the screaming and shouting Archie Brownlee. The connection to Peacock owner Don Robey came through a friend to the Birds, Reverend I.H. Gordon, host of a Cleveland gospel radio show and himself a Peacock recording artist. The Dixie Hummingbirds entered the relationship with Robey, infamous for his rough handling of artists who dared challenge his royalty counts, with their eyes opened. The records they made in partnership with Robey over the next two decades until his death in 1975 would forever secure the Dixie Hummingbirds’ reputation as one of the top groups in gospel and masters of the soul gospel sound.

The Peacock tracks collected here come from the first year of the group’s affiliation with the label. “What Are They Doing In Heaven Today” b/w “Wading Through Blood and Water” comprised the Dixie Hummingbirds debut release. “What Are They Doing” was a Paul Owens take on a C.A. Tindley composition, the performance up-tempo with responsive group harmonies over Bobo’s pulsing bass and occasional bursts of echo provided by studio engineers. “Wading” was Tucker’s  anguished response to the raging Korean War, a protest in neo-spiritual form. Paul Owens would also be in the line-up on “I Know I’ve Been Changed,” but then, dismissed from the group by James Davis for a “rules” infraction ュ Owens had been spotted at the race track betting on horses – he would be off to join the Swan Silvertones, not to sing again with the Hummingbirds until rejoining them in 1988.

anguished response to the raging Korean War, a protest in neo-spiritual form. Paul Owens would also be in the line-up on “I Know I’ve Been Changed,” but then, dismissed from the group by James Davis for a “rules” infraction ュ Owens had been spotted at the race track betting on horses – he would be off to join the Swan Silvertones, not to sing again with the Hummingbirds until rejoining them in 1988.

To fill the vacated space and also to better compete in a gospel market increasingly reliant on instrumental back-ups, the Dixie Hummingbirds would add Philadelphia guitarist and founding member of the Sensational Nightingales, Howard Carroll. Propelled by Carroll’s soulful rhythmic electric guitar, the Birds – James Davis, Ira Tucker, Beachey Thompson, and William Bobo – would go back into the Peacock studios with Don Robey supervising. The drums heard on the recordings – Robey’s idea – were not drums at all, but rather the Birds stomping on boards set up by Robey on the studio floor to pump up the beat. They would record “Lord If I Go” b/w “Eternal Life,” but most importantly, they would cut “Trouble In My Way,” a song written by Paul Owen’s brother-in-law, Billy Mickens, and brought by Owens into the group. With Owens gone, Tucker rushed to record the track, hoping to beat Owens and the Swan Silvertones to the punch. Sure enough, the Silvertones released their version on the Specialty label in the summer of 1952, but the Dixie Hummingbirds beat them by a few weeks, and the song would become forevermore identified with the Birds.

The Birds would go on to record many a best-selling track for Peacock, including their own 1973 Grammy-winning version of Paul Simon’s “Loves Me Like a Rock,” a tune that had raced up the pop charts but won no awards when they recorded it earlier that same year with Simon. The tracks collected here, though, throw a light on the revealing transitional period between 1939-1952 when the Birds line-up and sound were still fluid as they forged on to the definitive style that would make them gospel stars throughout the 1950s and beyond.

Footnote:

PHILADELPHIA, April 25 /2007 — Mr. James B. Davis, founding member and patriarch of the world-famous gospel group, the Dixie Hummingbirds, died in Philadelphia on Tuesday, April 17, 2007. Born June 6, 1916 in Greenville, South Carolina, Mr. Davis was the Hummingbirds leader from their inception in 1928 through his retirement in 1984. Mr. Davis guided the Hummingbirds to stardom in the 1950s with a “super group” consisting of leads Ira Tucker and James Walker, bass William Bobo, harmonist Beachey Thompson, and guitarist Howard Carroll. Their post-war recordings influenced singers as disparate as Jackie Wilson, Bobby Bland, the Temptations, and Stevie Wonder, and helped lay the foundation for doo-wop, soul, and Motown. The ‘Birds were among the first to bring gospel performance to secular venues like the Apollo, Carnegie Hall, and the Newport Jazz Festival. In 1973, Mr. Davis and the Hummingbirds collaborated with pop singer Paul Simon on “Loves Me (Like a Rock),” propelling the group to broader fame and winning them a Grammy for their own rendition.