Robert Lee “Strawberry” McCloud – Bloomington Breakdown – FRC749

By Teri Klassen

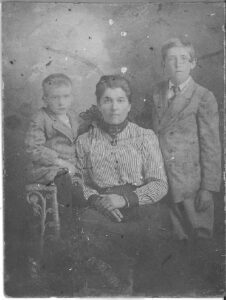

Fiddler/bass fiddler/heavy equipment operator Robert Lee “Bob” or “Strawberry” McCloud (1907-80) spent his first 30 years in the Bluegrass region of Kentucky, just west of the eastern Mountain region. Both areas were rich in old-time music, but the Bluegrass was more populated and tied to mainstream culture. According to Encyclopedia Britannica,

“The Bluegrass region is markedly different from eastern Kentucky, both physically and culturally. With a more northward orientation than its Mountain neighbour, the Bluegrass is more affluent and more cosmopolitan…” https://www.britannica.com/place/Kentucky/Cultural-life

It likely had more of a Black presence since, historically, that is associated with areas that had plantations and prosperous farms that could afford slaves.

The 1910 US Census shows Strawberry at age 2 in Bourbon County, then just south of Bourbon, in Clark, in 1920 and 1930. His father managed a 900-acre tobacco farm (according to a ca. 1978 newspaper interview) and later worked at a horse track near Lexington (according to Strawberry’s son Robert “Junior” McCloud [1944-]). The fifth of six children, Strawberry lived with his parents, Willard and Nora, until about 1925. He learned his first tunes from his father and two older brothers. Nearby fiddlers (White except as noted) included: Doc Roberts,

Strawberry’s “favorite” fiddler and a major influence though their styles differ (Madison County; 1897-1978); Van Kidwell (Madison; 1901-85); Jim Booker, African American (Jessamine; 1872-1940); George Lee Hawkins (Bath; 1904-91); Darley Fulks (Wolfe; 1895-1990); and Walter McNew (Rockcastle; 1912-98). Older-style fiddlers such as John Salyer (Magoffin; 1882-1952), William Stepp (Lee, Magoffin; 1875-1957), and Manon Campbell (Letcher; 1890-1987), tended to be in the nearby but more isolated Mountain area.

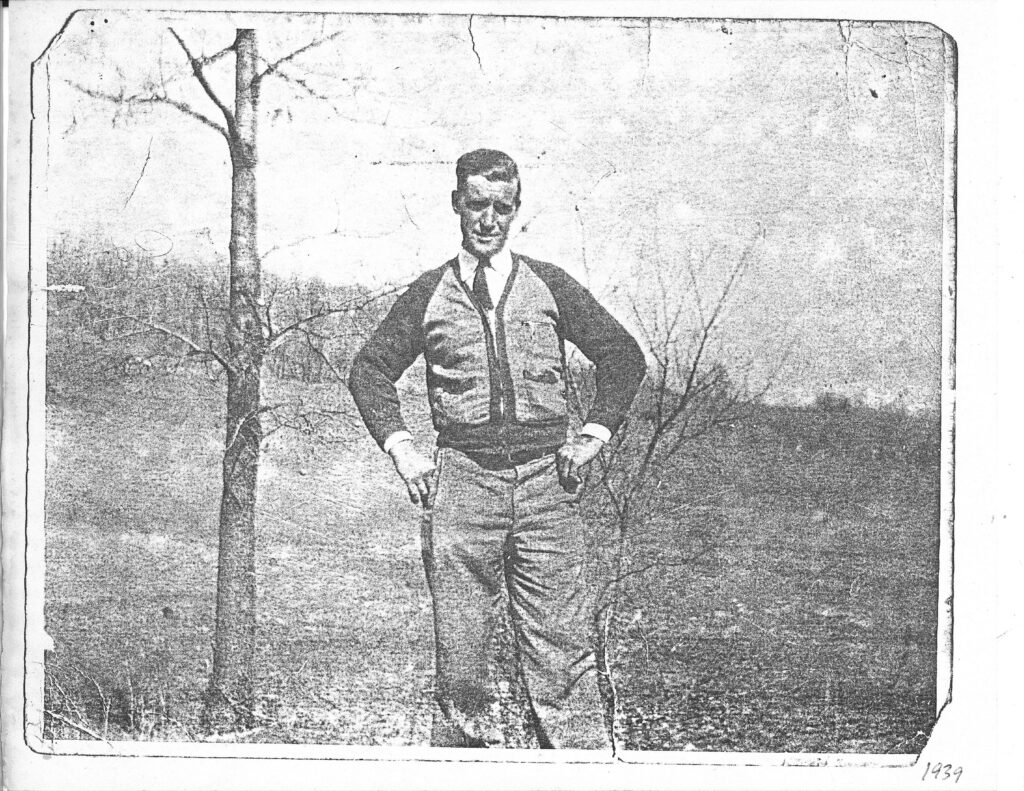

Strawberry expanded his musical horizons first by playing fiddle and bass fiddle at house dances (he told of walking to one in winter having styled his hair with lard, only to have it melt in the heat of the dance) and fiddle contests (he met Doc Roberts, who became a mentor and friend, in 1923 at a contest in Winchester, the Clark County seat). In his later years (the latter 1970s) he told younger musicians and a Bloomington Herald-Times reporter that he had played with the Skillet Lickers in the late 1920s and with Clayton McMichen’s Georgia Wildcats from 1930 to ’34 (see the newspaper article “Once a Skillet Licker…” and his “Folk Festival Autobiography” elsewhere on this website). It’s possible, however, that he added the Skillet Lickers part of the story for effect, as two younger-generation musicians recall that a few years earlier (about 1974), he told them he had played bass fiddle with the Georgia Wildcats but, asked if he had played with the Skillet Lickers, responded that he had not. We so far have not found Strawberry’s name on any Wildcats recordings, but his detailed memories lend credence to his account. For instance, he told of having to be at Louisville radio station WHAS at 7 a.m. to do live spots for Howell Furniture Co. and Arm and Hammer baking soda, of earning $65 a week (“good money in them days”), and of life on the road: “We went as high as five days and nights and never see a bed, just sleep in the car a-traveling” (see his “Folk Festival Autobiography”).

Mixed Race Music. In Strawberry’s youth, the 1910s to mid ‘30s, old-time music was a mixed-race culture in this part of Kentucky (and elsewhere), even in the Jim Crow Era. As John Harrod wrote in notes for Traditional Fiddle Music of Kentucky: Along the Kentucky River (Rounder CD 0377):

It seemed as if music had once provided a common ground where the racial codes of society might be temporarily suspended. Bands 11 through 20 are from [W]hite fiddlers who learned these pieces directly from this older generation of [B]lack fiddlers in Madison and Jessamine Counties (1997:14).

In this period, the “old-time” fiddle repertoire expanded beyond hoedowns and hornpipes with British Isles roots to include country blues and rags with Southern U.S. mixed-race origins and popular songs of the 1890s to 1910s (see Tony Russell’s Rural Rhythm on “the wide repertoire” of recorded country music in the mid 1920s to early ‘30s [2015:43]).

Perhaps the combined factors of the early-1900s rise of (question-authority) popular youth culture, post-World War I “Roaring ‘20s,” and Prohibition (1920-33) drew young people, especially in rural areas with mixed-race populations, to sometimes forego Jim Crow strictures (which had mainly urban applications, such as separate water fountains and theater seating). Darley Fulks told of learning “Martha Campbell” about 1915 (when he was about 20) from Black musicians in Mt. Sterling (Montgomery County seat). Introducing “New Money” at a 1978 festival workshop, Strawberry said, “That came out in 1913. The Colored people played against the Whites in Louisville, Kentucky, at the state fair, and my brother [Jack] learned it there from a Colored guy by the name of Walter Jones. . . So I learnt what I know a little about it from my brother, and then Doc Roberts out of Richmond, Kentucky, learnt me the rest” (Andy Cahan recording of a 1978 KSU Folk Festival workshop). Historical accounts of Doc Roberts, Jim Booker, Taylor’s Kentucky Boys, Owen Walker, Charlie Walker, and Van Kidwell also testify to old-time music as a mixed-race culture in this area at this time.

Repertoire. Later in life, 40 years after becoming a heavy equipment operator, changing music from full-time occupation to “pastime,” and relocating to southern Indiana (1937), Strawberry’s repertoire had grown to include mid-century pieces such as “Tennessee Waltz” (released 1948), “Sugar-Foot Rag” (1949; included on this CD), and “Fraulein” (1957). But in his retirement, settled in Bloomington, Indiana, and inspired, perhaps, by its old-time-music-and-dance revival scene, he revitalized many tunes of his youth. They account for most of the tracks on this CD, and fall in three main categories:

1) group- or step-dance-oriented hoedowns from an earlier era. Many are cross-regional (“Soldier’s Joy,” “Cripple Creek,” “Cumberland Gap,” “Forky Deer,” “Mississippi Sawyer,” “Sally Goodin’,” “Black-Eyed Susie,” “Flop-Eared Mule,” “Turkey in the Straw,” “Run, Boy, Run”); others hearken to the Kentucky Mountain/Bluegrass area (“Martha Campbell,” “Coon Dog” [not the Virginia-based Spangler tune], “Waynesboro,” “Buck Creek Gal,” “Brickyard Joe” [not on this CD]);. The tune Strawberry called “Paddy on the Turnpike,” though possibly original, is also in this style;

2) fiddle versions of 1890s-1910s popular songs: “Sweet Bunch of Daisies” (1894), “I Don’t Love Nobody” (1896), “Frankie and Johnny” (1904), “Casey Jones” (1909), “Silver Bell” (1911);

3) couple- and jazz-dance-oriented (foxtrot, two-step, shimmy, stomp, waltz) rags and blues of the 1910s-30s: “Darktown Strutters’ Ball” (1917), “Wang Wang Blues” (1920), “All I’ve Got’s Done Gone” (1925), “New Money” (1928), “Carroll County Blues” (1929); and (the possibly original) “Shimmy-She-Wobble.”

Strawberry’s style of playing old hoedowns seems influenced by his affinity for the rags and blues that were the rage in his youth. As evidence:

1) He plays only in standard tuning, mostly in the keys of G and C, including some hoedowns that older-style fiddlers tend to play in cross-tuning (AEAE or GDGD). He thus sacrifices (or works harder to get) some qualities facilitated by key-specific “wildcat” tunings (AEAE, AEAC#, ADAE, GDAD, etc.), such as droning and bow-rocking across two or three strings.

2) Scarce or absent are: single-pitch bowed trills (what Tommy Jarrell called “catching up the slack,” see Brad Leftwich’s Old-Time Fiddle: Round Peak Style, pp. 14, 17); intricate melodic variations exemplified by Doc Roberts (Kentucky; 1897-1978) and Ed Haley (West Virginia, eastern Kentucky and elsewhere; 1885-1951); and the common variation of playing a low part high or high part low (he does this, however, in “Cumberland Gap” and “Mississippi Sawyer”).

3) Strawberry’s strong suits include slides (sometimes chords fingered on two strings); blue (slightly flatted) notes and tremolo, usually on the high string; syncopation (emphasis on the off-beat, often at the ends of phrases); and staccato, sometimes several notes in a row, usually in the low part, producing a syncopated woodpecker (rat-a-tat-tat) effect (my term).

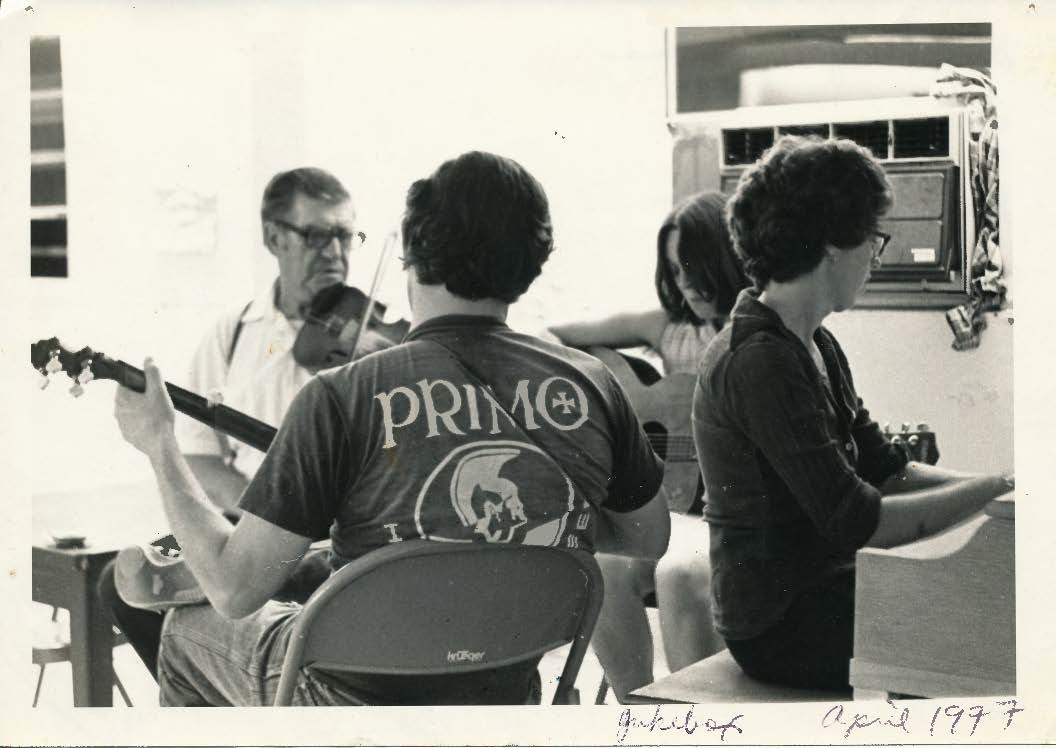

Strawberry McCloud at the Wednesday Night Dance, with Ted Hall, banjo; Teri Klassen, guitar; and Donna Doughten, piano. Courtesy of Teri Klassen. Photographer unknown.

Martha Marmouzé, long a regular at Bloomington’s Wednesday Night Dance, said, “[Strawberry] was so much fun to dance to. The music was sassy. We would sway our hips and drag our feet.” See also Steve Hinnefeld’s “Memories of Strawberry” essay here online; and Strawberry and the Bloomington Ramblers in concert here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gr4BBPPdasQ and here (with dancers) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_rsowWWpNAM at Eagle Creek Folk Festival in Indianapolis, probably 1977. See also Bruce Greene’s essay, “John Salyer’s Fiddle Style” (1992) https://oldtime-central.com/john-salyer-1882-1952-fiddler-from-magoffin-county-eastern-kentucky/

A factor in Strawberry’s style that likely promoted slides on the high string and possibly blue notes is that a 1936 crane accident during construction of the Fort Knox “gold vault” damaged his left-hand little finger. Doc Roberts visited him and told him how to compensate:

He said he’d show me how to slide my music, and he’d show me a good bow action. And I’ve got that today… He said the two most important things in music is bow action and good timing… I can’t use my hand like I used to ‘cause it gives me a little trouble by going to sleep. I have an artificial tube in my arm. (See “Strawberry’s Folk Festival Autobiography”)

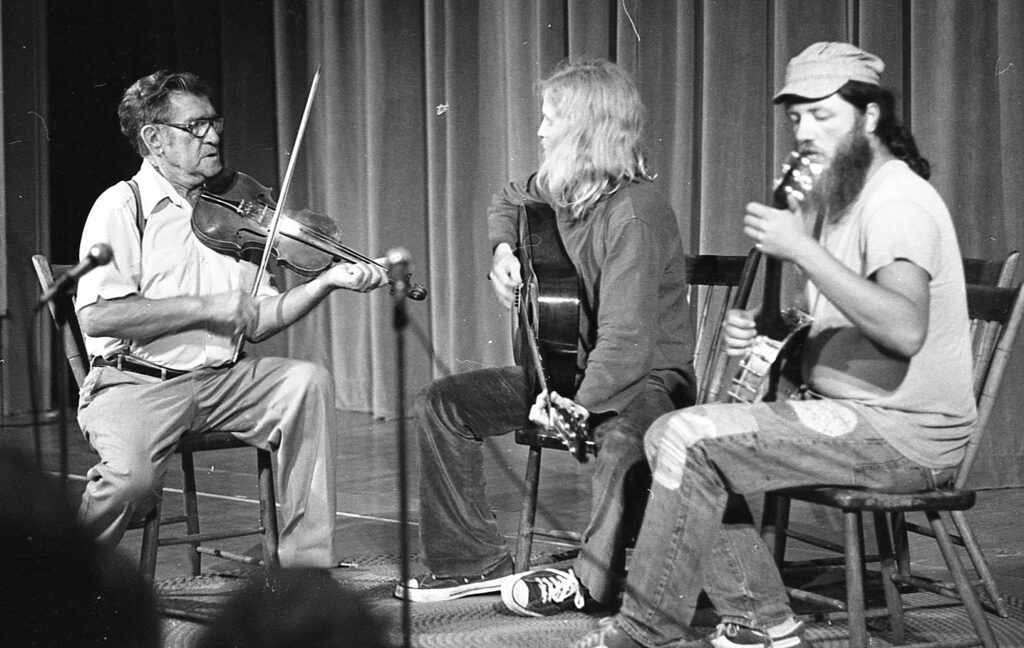

Strawberry McCloud with Andy Cahan and Tina Liza Jones, Kent State Folk Festival, 1978. Photographer: Kerry Blech.

Four decades later, it was Strawberry who visited Doc, hearing he had had a stroke. “We was crying like babies about old times. He never was beat in a contest, and now he can’t play a lick” (see “Strawberry’s Folk Festival Autobiography”). Doc died in 1978, Strawberry in 1980.

Many of Strawberry’s versions are irregular, or “crooked,” having what Kentucky tunes scholar Bruce Greene has called “structural freedom.” This means that the parts are not the standard length of eight or 16 beats but add or drop beats. Bruce observes it as a “fairly common” feature of older eastern Kentucky fiddlers such as John Salyer (1882-1952) and Manon Campbell (1890-1987). But given that many blues and rags are crooked, Strawberry may have perceived that playing a crooked version of an old tune enhanced its appeal to then-contemporary (1920s-early ‘30s) taste. Some comments he made when performing (captured on tape but not on this CD) suggest he knew that crooked versions were challenging and might entertain audiences and impress other musicians (including contest judges). Upon playing “Tennessee Wagoner,” he asks, “You ever hear it played like that?”; of “New Money,” he assures, “It’s easy to play it if you listen real close”; of “Billy in the Lowground,” “The changes are a little different than most people played”; and of “Sally Goodin’,” “I play it a little different.”

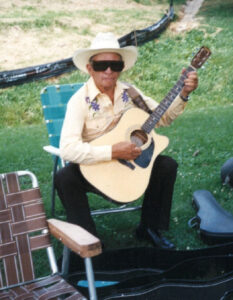

John Willie Myers (1918-2010), Strawberry’s nephew, shown here in Western dress at a family reunion in Bloomington, followed him readily on challenging crooked tunes such as “All I Got’s Done Gone.” Courtesy of Junior McCloud. Photographer unknown.

Clawhammer banjo. On the other hand, Strawberry’s embrace of clawhammer banjo accompaniment in his later years (the 1970s) upholds the comment in his “Folk Festival Autobiography” that he preferred “old-fashioned” music and had left the Georgia Wildcats partly because they were getting too “classy,” adding drums and saxophones (see the Wildcats’ 1938 recording, “[Can’t get nothin’ from old-time fiddlin’,] I’m Gonna Learn to Swing” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BzDESkKhfLk). In this respect, Strawberry preserved an aspect of old-style tunes that was falling from fashion in the 1920s-30s. Clawhammer banjo was largely absent from country rags and blues of that time; Alabama’s Stripling Brothers, Mississippi’s Narmour and Smith, and Tennessee’s Harkreader and Poteet, for instance, were fiddle-guitar duos. Doc Roberts recorded mostly with just guitar; the Georgia Wildcats had no clawhammer banjo. The Skillet Lickers sometimes had one, but fiddles, guitar, and vocals dominate on their recordings. A possible exception to this trend is Taylor’s Kentucky Boys’ recordings of “Grey Eagle” and “Forked Deer” (both with Black fiddler Jim Booker; 1927). Marion Underwood (White) plays old-timey-style banjo but it’s hard to tell if it’s clawhammer or finger-picking (thanks to Paul Brown and Brad Leftwich for input on this). Clawhammer banjo probably was more common in Kentucky’s Mountain region (which had fewer recording artists).

Strawberry McCloud with David Molk and Randy Marmouzé, New Harmony Festival of Traditional Music, 1977. Photographer: Gary Stanton.

Strawberry thus retained aspects of pre-World War I old-time music even as he jazzed up old-style tunes with techniques of mixed-race blues and rags. Banjo-player Randy Marmouzé (then in his 20s) followed him into this territory, adapting clawhammer rhythm to blues and rags even as fiddlers of Strawberry’s generation adapted old-time bowing to rags, blues, and popular songs.

Distinctive versions. Two factors that may underlie Strawberry’s distinctive versions are:

1) Early-1900s conditions in Kentucky’s Bluegrass region meant that old-time musicians in many cases got tunes via short-term face-to-face contact (such as at fiddle contests). Strawberry, and probably most other fiddlers, did not read music (even if they had, tune transcriptions likely were hard to come by) and, especially in rural areas, lacked electrical service for phonographs and radios. In these memory-dependent conditions, tunes inevitably changed, especially crooked and melodically complex ones.

Darley Fulks, born in 1895, recalled the challenge of remembering a tune he heard about 1915 when he was far from home without his fiddle:

Well, I was horseback and I had fifty mile to ride and I lived over here at Bethel… And I never got home til after daylight, and I hummed that piece all the way home so I wouldn’t forget it. And another one they played was “Paddy on the Turnpike” but I thought more of “Martha Campbell” because it had more music in it. I couldn’t hold them both and I held on to that one. Now that coarse [low] part, they don’t play that no more, but them [C]olored folks, they played it. https://fieldrecorder.org/darley-fulks-kentucky-wild-horse-tune-notes/

Under these conditions, the pre-cassette recorder-and-smart phone-era, absence of technology promoted development of different tune versions.

2) The ability to develop a distinctive version or create a new tune, as opposed to accurately executing an established version, may have been a mark of a master fiddler, inspiring admiration and respect. The back-story of a C-tune that Strawberry brought back from the 1977 West Virginia State Folk Festival in Glenville suggests how this process might have occurred. He called it “Virginia Rag” and said he’d heard it at Glenville but gave no specific fiddler’s name as his source.

With input from West Virginia fiddler and tunes scholar Gerry Milnes, we realized that the first part of Strawberry’s “Virginia Rag” is close to that of “Fun’s All Over,” a tune played in West Virginia and eastern Kentucky. But the second part differs. Ohio fiddler and tunes scholar Whitt Mead is reminded of the low part of “Little Brown Jug;” the low part of “Texas Gals” came to my mind.

Ohio musician Joe LaRose, who with other members of the Radio Aces stringband had jammed with Strawberry at Glenville (old-time tunes scholar and fiddler Kerry Blech of the Radio Aces recorded the session), recalled that the band had been playing eastern Kentucky fiddler J.P. Fraley’s version of “Fun’s All Over” at that festival. Thus, a possible scenario is that Strawberry heard the Radio Aces playing the tune at Glenville, liked it, perhaps played along with it, tried to memorize it (possibly recalling it from his youth in Kentucky), practiced it when he got home, filled in what he didn’t remember with phrases from other tunes, and not knowing the name, made one up that recalls where he learned it (“[West] Virginia”) and the jaunty setting he gave it (“Rag”). Rather than give up on the tune because he didn’t remember all of it, he pro-actively built it into a new tune he could show off to appreciative friends back home.

Conclusion. Strawberry’s music is a lens onto how folk musicians engage with change, striking a balance between fascination with (or rejection of) what preceded and what is new on the scene. He held on to the old tunes, the legacy of those who came before, but re-tailored them, sacrificing some features but invigorating them with others. It’s a testimonial to the endurance of the music that its tunes are plastic; given an adventurous taste and sufficient ingenuity (driven by necessity to invention, perhaps, when lacking access to the source), a fiddler can hitch a tune template to one style or another, varying notes and rhythm.

Old-time-music devotees will recognize most of Strawberry’s tunes but be wide-eyed (or shake their heads) at some of his settings. Coming of age in what music historian Tony Russell calls the “halcyon age of recorded country music,” he preserved old tunes but adapted (some might say “corrupted”) them to techniques of then-modern rags, blues, and popular songs, even as popular taste moved on to Western swing (late 1930s), then Western-style country (1940s) (Russell 2015:43, 40) and bluegrass (1940s). To the credit of his young protégés, they open-mindedly embraced this uncharted concept of “old-time.”

FRC749 Acknowledgments

It took a community to put this project together, and we are thankful to these members of ours who helped bring it to fruition.

John Bealle, John Beland, Kerry Blech and the Kent State Folk Festival, Harry Bolick, Jon Bowman, Paul Brown, Mike Bryant, Andy Cahan, Andrea Carter, Jim Cauthen, Joyce Cauthen, Jeff Claus, Ron Cole, Donna Doughten, Stephen Downey, Wayne Erbsen, Mark Feddersen, Dan Gellert, Susie Goehring, Tim Goodall, Ted Hall RIP, John Harrod, Karen Horton, Hawk Hubbard, Judy Hyman, Michael Johnson, Joe LaRose, Brad Leftwich, Laura Ley, Theresa Malone, Bill Mansfield, Martha Marmouzé, Randy Marmouzé RIP, Junior McCloud, Whitt Mead, Gerry Milnes and the Augusta Heritage Workshop, Ren Oschin RIP, Chris Rietz, Gary Stanton and WFIU radio station, Judy (McCloud) Taylor RIP, Ben Thompson, Jill Vass, Larry Warren and the Slippery Hill tunes website.

FRC749 Bibliographical Sources

Augusta Arts and Culture website https://augustaartsandculture.org/document/strawberry-mccloud-tunes-1-of-2-10-21-1976/

Bealle, John. Old-Time Music and Dance: Community and Folk Revival. Quarry Books (2005)

Berea College Special Collections and Archives website

Bloomington (Indiana) Herald-Times, Tom Ritchie (staff writer). “Once a Skillet Licker, Now an Art Perpetuator: Strawberry McCloud—Fiddlin’ and Fishin’” (ca. 1978)

Bluegrass Messengers website

Carter, Thomas, with Thomas Sauber. “I Never Could Play Alone”: The Emergence of the New River Valley String Band, 1875-1915. In Arts in Earnest: North Carolina Folklife, eds. Daniel W. Patterson and Charles G. Zug III. Duke University Press (1990)

Digital Commons @ Connecticut College

Greene, Bruce. “John Salyer’s Fiddle Style” Oldtime Central website (1992) https://oldtime-central.com/john-salyer-1882-1952-fiddler-from-magoffin-county-eastern-kentucky/

Harrod, John. Comments for Darley Fulks: Kentucky Wild Horse. Field Recorders’ Collective 716 (2015) https://fieldrecorder.bandcamp.com/album/frc-716-darley-fulks-kentucky-wild-horse-john-harrod-collection

Harrod, John. Tune Notes for Darley Fulks: Kentucky Wild Horse. FRC 716 (2015) https://fieldrecorder.org/darley-fulks-kentucky-wild-horse-tune-notes/

Harrod, John. Track notes for Kentucky Fiddlers Home Recordings Vol. 1. FRC 732 (2020) https://fieldrecorder.org/ky-fiddlers-vol1-track-notes/

Internet Archive

Jamison, Phil. Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance. University of Illinois (2015)

Klassen, Teri. “Strawberry McCloud and Old-Time Music in Bloomington,” PowerPoint presentation at the Bloomington Early Music Festival.

Leftwich, Brad. Old-Time Fiddle: Round Peak Style. Mel Bay (2007)

McCloud, Robert L. (Strawberry). Strawberry’s Folk Festival Autobiography (ca. 1978)

McCloud, Strawberry, and the Bloomington Ramblers, “Bloomington Breakdown,” video with Bloomington dancers at Eagle Creek Folk Festival, Indianapolis, probably 1977. Posted by Brad Leftwich https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_rsowWWpNAM

McCloud, Strawberry, and the Bloomington Ramblers, “Sally Goodin’,” video at Eagle Creek Folk Festival, Indianapolis, probably 1977. Posted by Brad Leftwich https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gr4BBPPdasQ

[The] Milnes Collection. Recordings by Gerry Milnes https://augustaartsandculture.org/document/strawberry-mccloud-tunes-1-of-2-10-21-1976/Notable Kentucky African Americans Database

Oldtime Tunes.com

Rorrer, Kinney. Rambling Blues: The Life and Songs of Charlie Poole. Old Time Music (1982)

Russell, Tony. Rural Rhythm: The Story of Old-Time Country Music in 78 Records. Oxford University Press (2021)

Slippery Hill tunes website

Southern Folklife Collection at University of North Carolina libraries (listed as SFC Audio Cassette 637, “Strawberry McLeod [sic] and Wayne Erbsen,” side 1; and side 2 https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/search/collection/sfc/searchterm/sfcaudiocassette_637!20525/field/contri!escri/mode/exact!exact/conn/and!and/order/relatid/ad/asc/cosuppress/0

Stanton, Gary. “All Counties Have Blues: County Blues as an Emergent Genre of Fiddle Tunes in Eastern Mississippi” In North Carolina Folklore Journal (November 1980) https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll43/id/3996.

Traditional Fiddle Music of Kentucky: Up the Ohio and Licking Rivers, Vol. 1. Recorded by Guthrie T. Meade, John Harrod, and Mark Wilson. Annotated by Mark Wilson. Rounder CD 0376 (1997)

Traditional Fiddle Music of Kentucky: Along the Kentucky River, Vol. 2. Recorded by Guthrie T. Meade, John Harrod, and Mark Wilson. Annotated by John Harrod. Rounder CD 0377 (1997)

Traditional Tune Archive website

Wikipedia

Youtube