See Texas Fiddle Bands (FRC409) and P.T. Bell (FRC410)

From Bill Owens “Tell Me a Story, Sing Me a Song”

In Texas, as in other parts of the frontier west of the Alleghenies, the settlers were generally liberal in matters of personal belief and religious freedom.

Paradoxically, the freer they were in congregational governance, the stricter, the more conservative they were in rules of personal conduct, especially in those that dictated acceptable forms of entertainment. Drinking and gambling were flirtings with the devil, or giving over to him entirely. So was card-playing. Again and again people said to me, “I wouldn’t have a deck of cards in my house.” I could ask for miles around and not find a deck for bridge or for the non-betting game mockingly called “hell” when the word, often joined with “fire” was acceptable only in sermons or other religious contexts.

Square dancing was a greater evil, and round-couple-dancing greater still: they were done to the fiddle. John Taylor, a frontier Baptist preacher, wrote: “It may be taken for granted, that what is called a good fiddler, is the Devil’s right hand man.” Generations of preachers perpetuated the belief. Listening to fiddle music was all right. So was patting a foot to a lively tune. But a member in good standing could be “churched” for one sashay on the dance floor or for staying to watch and listen after the dancing started. This discipline was severe and swift. If a member found guilty by the congregation did not repent with acceptable humility, or if there was a question of the sincerity of his repentance, fellowship was withdrawn-a harsh punishment if all his neighbors and friends were in the church.

Some were hardy enough or irreverent enough to withstand such pressures. Fiddles and fiddlers could be found-fiddles carried across the Atlantic or fashioned from gourd and stick and animal gut in the wilderness, fiddlers playing tunes by ear, tunes brought across the water or made up as the urge arose. Wherever fiddlers played there were some ready to dance to the tune, and callers to guide them though square dance steps like “swing your partner” and “do see do and a little mo’ dough.” In spite of preaching and “churching,” both square and round dancing survived. In less godly communities, they throve. Fiddlers made up new tunes, callers made up new calls, and more and more of the frontier experience entered folk tradition.

Like the popular ballads, fiddle tunes and dance calls had gone in and out of the oral tradition and in again. Country dances — reels, hornpipes, and the longways, the Sir Roger de Coverly — had been danced to fiddle and bagpipe throughout Britain long before they were brought to court, and the tunes refined and published.

At the French court formal directions were prescribed for lords and ladies, one of which in Texas became

Bow to your partner, bow to your taw,

Bow to that gal from Arkansaw.

French words in barely recognizable form were preserved on the frontier in square dance calls: sashay for chasse, do see do for dos-a-dos, aleman (as in aleman left) for allemande.

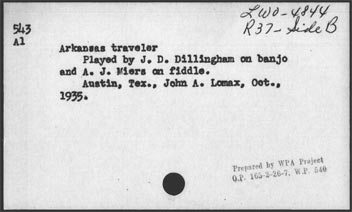

P.T. Bell

Though fiddle tunes like “Shakespeare,” “The Fisher’s Hornpipe,” and “The Campbells Are Coming” retained their names, the arrange-ments of notes and manner of playing became Americanized. Played by ear, an untrained ear, the tunes could be expected to become cruder the farther west they traveled. Imitations were often cruder still, even those created out of American events or places and bearing titles genuinely American. For instance, “The Eighth of January, or the Battle of New Orleans” celebrates General Andrew Jackson’s defeat of the British in the War of 1812. “Natchez under the Hill” took its name from the tougher part of Natchez, under the bluff, down by the river. Samplings from dozens of fiddle tunes extant reflect various frontier experiences: “Leather Britches,” “Cattle in the Canebrake,” “Hell among the Yearlings,” “Arkansas Traveler,” “Turkey in the Straw.”

In 1941 I spent several sessions recording Peter Bell of Carrizo Springs, a descendant of Scots and probably Scotch-Irish pioneers, seventy-four years old, filled with the sound of bagpipes, which he did not know, and fiddles, which he had played from early boyhood. He recorded thirty tunes and, as he said, “had not run out of fodder” when I had to leave. Selected titles from among them suggest move-ments of his family as pioneers: “The Campbells Are Coming,” “In-dian War Whoop,” and from the Civil War “Jeff Davis,” “Yankees on the Hill,” “Sixty Days in Georgia,” and an unnamed march his father had learned while a rebel soldier. Other titles he thought of as lightly humorous: “Snowbird in the Ash Bank,” “Sugar in the Coffee,” and “Dig Big Taters in the Sandy Land.” He also played polkas, schot-tisches, and waltzes, all of them seeming nearer to some European model.

Square Dance Calls and Play Parties

Square dance calls, often improvised at the moment, were as crude as the fiddle tunes, and certainly as Americanized. Two examples prove the point:

Git yo’ pardner, hit her on the head,

If she don’t like biscuits, feed her cornbread.

And

Pardners to your places, straighten up your faces,

And take a good chaw of tobaccy O;

If your left foot’s lazy and your right foot’s crazy

You better go to heaven in a hacky O.

A good caller knew enough calls to last all night long. He could also liven the dance by improvising compliments for the ladies and banter for the men.

“Churchified” people found their own way to dance, without fiddler or caller or preacher’s damnation. They set their calls to tunes and danced to their own singing. Thus the play-party, also called singing games or ring games, came into being as a joining of square dancing and children’s games. The genius was not in creating but in adapting. Children’s games like “London Bridge Is Falling Down” persisted all across the frontier. “Drop-the-Handkerchief” became a “choosing game,” and later a popular song, with the addition of words and tune:

Itiskit, itaskit, a green-and-yellow basket,

I wrote a letter to my love and on the way I dropped it,

Dropped it, dropped it,

A little boy came along and put it in his pocket.

Innocently or not, boys and girls acted out the courtship ritual of “We’re Marching around the Levee”:

We’re marching around the levee,

We’re marching around the levee,

We’re marching around the levee,

For the right shall gain today.

Go in and out the window,

Etc.

Go forth and choose your lover, Etc.

I measure my love to show you, Etc.

I kneel because I love you, Etc.

Goodbye, I hate to leave you, Etc.

Transition from such games to play-party games required little imagination. Old calls were adapted to old or new tunes. New calls and tunes were made up, sometimes in a nonsense mingling of the old and new. In “Skip to My Lou” the longways dance that had been the Sir Roger de Coverly in England became the Virginia reel and then a play-party game. I never saw the Virginia reel danced at a square dance but it was popular at play-parties, either with the dancers sing-ing the directions or improvising on words they all knew:

Flies in the buttermilk, skip to my Lou,

Flies in the buttermilk, skip to my Lou,

Flies in the buttermilk, skip to My Lou,

Skip to my Lou, my darling.

Little red wagon painted blue, Etc.

Can’t get a red bird a blue bird’ll do, Etc.

Settlers arriving early in Kentucky found thousands of buffaloes grazing in thousands of acres of canebrake. Some ingenious person, probably a square dance caller, combined square dance calls and parts of the Kentucky scene into “Shoot the Buffalo”:

Rise you up, my dearest dear,

And present to me your hand,

And we’ll all run away

To some fair and distant land.

REFRAIN

Where the ladies knit and sew,

And the gents they plow and hoe,

We’ll ramble in the canebrake

And shoot the buffalo.

Oh, the rabbit shot the monkey,

And the monkey shot the crow;

Let us ramble in the canebrake

And shoot the buffalo.

All the way from Georgia

To Texas I must go,

To rally ’round the canebrake

And shoot the buffalo.

Where the women sit and patch,

While the men stand and scratch,

We’ll ramble through the canebrake

And shoot the buffalo.

In parts of Texas “Dance Josey” became so popular that play-parties are still remembered as “them old Josey parties.” The song was easily adapted to the place, the time, the dancers, or the need for a laugh:

Chicken on the fence post, can’t dance Josey;

Chicken on the fence post, can’t dance Joe;

Chicken on the fence post, can’t dance Josey;

Hello Susan Brown ee o.

Hold my mule while I dance Josey, Etc.

Big foot Charlie can’t dance Josey, Etc.

Not surprisingly, some of the play-party songs satirize religion. One verse of “Weevily Wheat” goes

Take her by the lily-white hand, Lead her like a pigeon,

Make her dance the Weevily Wheat And scatter her religion.

In “Old Joe Clark” there is a verse sung in a minor key:

Old Joe Clark had a yellow cat, She would neither sing nor pray;

She stuck her head in a buttermilk jar And washed her sins away.

I often heard of people “churched” for going to dances, but never for going to play-parties, though the latter did not entirely escape the censure of the “deacons’ corner” pious. “The Wicked Daughter,” a widely known religious ballad, also sung in a minor key, has an admonition for “young people who delight in sin.” This young woman’s sins were at least threefold:

Young people who delight in sin,

I’ll tell you what has lately been;

A lady who was young and fair,

She died in sin and dark despair.

She went to parties both dance and play

In spite of all her friends could say.

“I’ll turn to God when I get old

And then he will redeem my soul.”