By Eugene Chadbourne

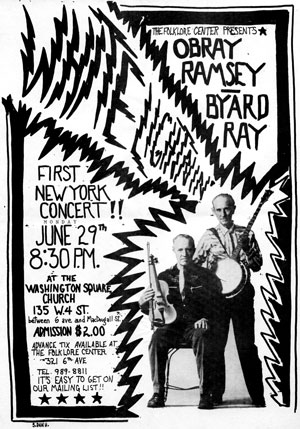

Obray Ramsey is the banjo-picking cousin of old-time music instrumentalist Byard Ray, and the two worked regularly as a duo until they were “discovered” playing at an Asheville folk festival during the folk music revival of the ’60s. From that point on, the two men’s musical career took a strangely twisted path. Late-night television mongers who may have made it all the way through the strange psychedelic rock western Zachariah, may wonder who the two old-time musicians are that show up in one of this epic’s many strange musical wonders, and the answer would be Ray and Ramsey. The same viewer may also wonder why they have become attached to their seat with cement, the only condition under which an intelligent human being would endure the length of the aforementioned film. In 1962, producer John Simon invited the duo to New York City, or “thawt New Yawk,” as it is known south of the Mason-Dixon Line. The players were swept into experimental recording projects with a strange combination of players, although perhaps something a bit more threatening than a broom was needed to get these old-timers to pick alongside players such as avant garde classical guitarist Sam Brown, studio pro and funkmeister Chuck Rainey, rhythm and blues session drummer Herb Lovelle, sarcastic pianist Dave Frishberg, and even a black gospel group, the Wondrous Joy Clouds. File Under Rock was the name of the first album edited together from these sessions, the players collectively given the ad hoc group was given the name White Lightnin’, at that time a slang term for a type of LSD as well as the traditional name for home-brewed liquor from the mountains. A second album entitled Fresh Air was also released, notable for a pleasant Bob Dylan cover version featuring the old-time musicians performing with the collegiate folkies Judy Collins and Eric Anderson, resulting in a memorable meeting of the old and new in folk music.

Ramsey has also recorded on his own, including an album of folk music for Prestige International. He is considered one of the finest banjoists for accompanying singing and has been compared favorably with Doc Boggs. In the late ’50s, he was a member of fiddler Tommy Hunter’s Carolina String Band with the leader’s sister Nan Hunter and her husband George Fisher. The archival type Deadheads might have his name on the tip of their tongue (along with lord knows what else) via Grateful Dead’s cover version of Ramsey’s song “Cold Rain and Snow,” one of many traditional Appalachian numbers this band used to jam out on. Ramsey and his music is also credited with having a large influence on the writer Manly Wade Wellman, a creator of science fiction, adventure, and mystery stories who once beat out William Faulkner in a writing contest. Through a friendship with folklorist Vance Randolf, Wellman met Ramsey during one of several collecting and recording trips in hillbilly territory. Ramsay is also a member of an elite club of musicians that have had songs written about them, in this case the ditty “Ballad of Obray Ramsey,” recorded by Matthew’s Southern Comfort on their 1970 album Second Spring. Ramsey also gave some music lessons to Mel Lyman, a musician who would eventually join the Jim Kweskin Jug Band as a replacement member and go on to supposedly form his own mind control cult in the Bay Area. Despite basically being a farmer and banjo picker, Ramsey just couldn’t seem to avoid contacts with weird ’60s stuff. ~ Eugene Chadbourne, All Music Guide

Obray Ramsay and Byard Ray

A lifetime musician, this North Carolina fiddler and banjo player received a National Endowment for the Arts grant and did a smattering of recordings in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Then Byard Ray pretty much slipped out of both the sights and minds of old time music enthusiasts, not even earning a nod of recognition from collectors who know the name of similar artists from the ’20s who made one or two records. Ray began playing fiddle when he was seven, his greatest inspirations were players born in the mid- to late 19th century, such as J. Dedrick Harris, Ashbury McDevitt, and Ray’s great uncle, Mitchell Wallin. His natural talent on the instrument was kept a secret from everyone but his brother, Otis, because the youngsters had been strictly forbidden to touch the instrument out of fear that they would wreck it. Finally the truth came out when the two brothers were hanging around one day with a visiting fiddler, who thought he would do the little boy a favor and give him his first fiddle lesson. Despite Ray’s account of the tale, in which the fiddler threatens to kill his mother if she “whups” the boy for touching the fiddle without permission, fiddling seems to have been a family tradition with players such as great grandfather Morris Gosnell, his mother Rilla May Wallin, and his father William Morris Ray. And those are just the relatives whose names he could remember.

Ray grew up in a tradition of music, stories, and ballads being passed along orally among family members and friends in the community. He also adapted to modern times and the more urban environments that developed, in which the instruction of this type of cultural material began to be focused around university settings. By the ’80s, Ray had become a fiddle and banjo teacher at a variety of colleges, including Berea College in Kentucky and Warren Wilson College in the mountains of North Carolina. Students at such institutions actually encouraged Ray to record his first solo project, Traditional Music of Southern Appalachia, pressed on vinyl by Durham’s Sounds Good Studio, complete with an outlandish psychedelic cover. This was not his first recording by any means. He participated in two albums done during the folk revival of the ’60s, focusing on numbers done by Ray in tandem with another musical family member, his cousin Obray Ramsey, a banjoist. But although the two were used to playing as a duo, producer John Simon lured them to New York City, where they performed along with a studio band featuring a strange range of players, including the sometimes avant-garde classical guitarist Sam Brown, studio pro and funkmeister Chuck Rainey, drummer Herb Lovelle, the amusing pianist Dave Frishberg, and even a black gospel group, the Wondrous Joy Clouds. The result of this collaboration certainly sound intriguing, if anyone can find a copy of the record. It was entitled File Under Rock, and the ad hoc group was given the name White Lightnin’, at that time a slang term for a type of LSD, as well as the traditional name for home-brewed liquor from the mountains. A second album, entitled Fresh Air, was also released, meaning someone must have been happy with the initial results. The latter recording is notable for an interesting Bob Dylan cover version of “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” featuring the old time musicians performing with softer folkies Judy Collins and Eric Anderson. Slightly more accessible through the archival world of late-night television is the drug-soaked hippie western Zachariah, another strange project Ray and Obray got into via a connection of the White Lightnin’ project. It is safe to say that this film represents the largest audience exposure Ray’s music ever received, even if it was a film that sank like a stone(d). He also recorded for several labels with the Laurel River Valley Boys, also featuring Ervin Lewis and John Ray.

In the early ’70s, he formed a string band named the Appalachian Folk, and created an album based on the group’s repertory. Membership included Lou Therrell on banjo, Vivian Hartsoe on guitar, and Arlene Kesterson on bass.

His daughter, Lena Jean Ray, is also an accomplished singer of mountain ballads and traditional material. His granddaughter, Donna Norton, after initially rebelling from hearing so much of this type of music around the house, became interested in it after all when she went away to college in New York City and found out how much her fellow students liked Appalachian music. She began performing in a duo with Lena Jean shortly thereafter.