Lowe Stokes, Georgia Fiddler – FRC723

By Joe LaRose

A previous version of this article served as liner notes for Heritage 048, Georgia Fiddle Bands, ©1983 Heritage Records.

Of the many legendary fiddlers from old time music’s “Golden Age,” the period of commercial recording from the mid-twenties to the early thirties, Lowe Stokes seemed to have an aura of myth that went beyond his superb fiddling on records by the Skillet Lickers and others.

His raspy voice and no-nonsense delivery heard on the Skillet Licker’s spoken skit records suggested something of a scrappy guy. But when one considered that, at the height of his success, he lost his right hand to a shot gun blast only to go on fiddling using a hook to hold his bow, his reputation as—in fellow Skillet Licker Bert Layne’s words—“one tough fella,” was ensured.

Born Marcus Lowell Stokes on May 28, 1898 in Elijay, in the mountains of north Georgia, Lowe’s legend was building even as a young man. In 1924 he defeated long-reigning Georgia fiddle champion Fiddlin’ John Carson in Atlanta’s annual Old Time Fiddlers’ Convention, playing “Hell Broke Loose in Georgia.” His victory was described in a Literary Digest article that was read by poet Steven Vincent Benet, inspiring him to write “The Mountain Whippoorwill,” a poem whose hero was based on the young Lowe.

In the late 1920s, Lowe was brought into the Skillet Lickers, Columbia Records’ top hillbilly recording band, by his friend and arguably fiddling-equal, Clayton McMichen, who was feeling hobbled by being paired in the group with the somewhat old-fashioned Gid Tanner. Lowe and Clayton created a densely-textured unison (and with Bert Layne triple) fiddling approach that powered through some of the band’s best sides.

Lowe appeared on Skillet Lickers records and on records fronting his own bands until the incident on Christmas Day, 1930 that almost ended his career. As Bert Layne told it, Lowe and his brother had gone to see a bootlegger about getting some whiskey for Christmas. An argument occurred, resulting in someone pointing a shotgun at Lowe’s brother. Lowe grabbed the barrel and the gun fired, taking his right hand almost off. A country doctor finished the amputation while Lowe drank a half pint of liquor. When Bert heard what had happened and rushed to see Lowe, he found him “up in a barber shop getting a shave. Talk about a man that had a constitution—I never saw nothing like it.”

The Home Town Boys, c. 1924: Clayton McMichen, Bob Stephens Jr., Bob Stephens, Lowe Stokes. Photo courtesy Joe LaRose

Lowe thought his career as a musician was over. Fortunately, former mechanic McMichen fashioned an attachment that allowed Lowe to hold a bow, and he went on as a fiddler, even playing on a few more Skillet Licker sides.

Lowe fiddled in various road house bands in subsequent years before moving in the 1940s to the Tulsa, Oklahoma area to work in cowboy actor Ray Whitley’s band. It was at his home in Chouteau in eastern Oklahoma that I first visited Lowe in 1981, having learned of his whereabouts from Bert Layne. Gary Hawk, Tim Goodall, and I had visited Bert a few years earlier at his home in Covington, Kentucky after reading an interview with him that appeared in Old Time Music magazine. Bert informed us that Lowe was alive and well, but hadn’t played in a long time.

I wasn’t the first young old-time-music enthusiast to visit Lowe. Rich Nevins had extensively interviewed him in the early 1970s; his research became the basis of the liner notes to a County Records Skillet Lickers release (that record and Nevins’ notes turned me into a huge fan of Lowe’s). Lowe had also been visited at his home by Brad Leftwich. Lowe had no fiddle at the time, and hadn’t played in 17 years, so I thought I’d never actually get a chance to see him play. Nevertheless I still remember the thrill I felt just sitting in his living room talking with him.

In the spring of 1982, one of Lowe’s local musician friends (whose brother happened to make fiddles) gave Lowe a new fiddle with the necessary equipment fashioned so that he could play it (a short post coming up between two strings between the bridge and fingerboard to keep the bow from sliding up the neck, and a pivoting attachment for his prosthetic hand that held the bow). Shortly after, Lowe’s wife, Hazel, phoned me to say that Lowe was fiddling again. That was about all it took to get me, Kerry Blech, and Lee McGrogan in the car and headed for Oklahoma, guitars and fiddles in tow!

Once again, Lowe and Hazel, with generous hospitality, welcomed me to visit and stay a few days, this time with two friends. No mention was made at first of when—and if–we would get to hear Lowe play. But at some point early on Lowe disappeared into his bedroom, and after taking a little time to put on his bow-arm attachment, came walking back into the living room, playing his fiddle as he walked. I remember the tune as “Soldier’s Joy” (maybe Kerry remembers it differently). No matter, it was Lowe playing fiddle, and his characteristic style was right there. Over the next couple of days Kerry and I accompanied Lowe on guitar as the tunes, one by one, came back to him.

It’s something to think that it was only five months between the time Lowe started fiddling again and his performances at the Brandywine Festival. He was a really good sport about agreeing to participate. Not only did it mean a long plane trip to Maryland, at his age of 84, but also all the uncertainties of performing for a fan-base that was largely unknown to him. He said that he hoped his playing wouldn’t disappoint the attendees; I tried to assure him that they would be enthused just to meet him and talk with him, and if he played only as well as he was now able, that would be just fine.

Lowe spent the intervening months practicing with his local friends, banjoist Ray Smith and guitarist Bob Cowan. The trio had regular picking sessions at either Lowe or Ray’s house, and even performed out, furnishing between-innings entertainment at a local ball game. Lowe’s fiddling was getting better and better.

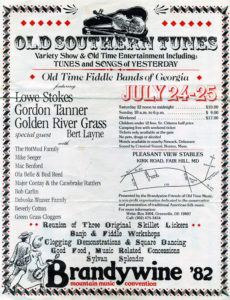

Having as its theme the fiddle bands of Georgia, the 1982 Brandywine Mountain Music Convention, held on July 24 and 25 in Fair Hill, Maryland, would stage a reunion of former Skillet Lickers and people in their circle: Lowe Stokes, Bert Layne, Gid Tanner’s son Gordon (who very sadly suffered a fatal heart attack on the eve of the festival), Clayton McMichen’s Georgia Wildcats guitarist Slim Bryant, and McMichen’s daughter Juanita Lynch.

The recordings of Lowe on this CD were taken from three different performances at the festival: a panel-presentation on the main stage with Lowe, Bert Layne, Slim Bryant, Juanita Lynch, and me as interviewer; a smaller-stage interview/performance with Lowe accompanied by me on guitar; and a main stage performance with Lowe and his “pickup band,” which included Mac Benford on banjo and me on guitar. The panel-presentation proceeded a bit staidly until it sprang to life—and that is the moment you hear on this CD—when Bert Layne took on his old role as emcee for the shows they used to do, talking about the Skillet Lickers, telling a few jokes, and finally giving a great introduction to Lowe, who launched into “Sally Gooden.” The full band performance is another great moment, for Lowe is playing wonderfully. He seems to be having a good time—WE certainly were!

Main Stage at Brandywine: Joe LaRose, Lowe Stokes, Gary Hopkins, Mac Benford. Photo courtesy Marianne Kovatch.

Given the short time he had been back to fiddling, Lowe’s working repertoire at the time of the festival, though not extensive, was strong, and a good representation of many of the tunes that were commonly played in north Georgia in Lowe’s day and heard on Skillet Lickers’ records: “Sally Goodin,” “Hell Broke Loose in Georgia” (the tune with which Lowe won the 1924 Atlanta Old Time Fiddlers’ Convention), “Georgia Wagoner,” Dance all Night with a Bottle in Your Hand,” “Bucking Mule,” “Liberty,” “Shortenin’ Bread,” and “Sugar in the Gourd.” Lowe’s versions of “Billy in the Low Ground,” “Citaco,” and “Katy Hill” were originally heard on 78s on which Lowe was the only fiddler (“Billy in the Low Ground” and “Katy Hill” pairing him with the Skillet Lickers’ famed guitarist Riley Puckett and “Citaco” played over a narration by Bert Layne).

Lowe had learned his version of “Katy Hill,” a title common in north Georgia for the tune often known elsewhere as “Sally Johnson,” from his mentor, Alabama fiddling legend Joe Lee; Lowe said that he had won many contests playing this tune. “Citaco,” the title referring to a community in the mountains near Chattanooga, was originally a tune Lowe had known as “Down to the Wildwood to Shoot the Buffalo.” “House of David Blues” represents the type of jazzy, blues-tinged number that Lowe, Clayton, and Bert loved to play but whose efforts to get them on record were usually rebuffed by Columbia A&R man Frank Walker, who wanted the boys to stick to the old time tunes that sold much better.

I hope that Lowe enjoyed his Brandywine experience. He certainly brought a lot of joy and excitement to those of us who were there. His life as a fiddler certainly had its ups and downs, but I’m glad he was there to show us how it’s done one last time. I know that the festival gave him an opportunity to see, through a knowledgeable young audience eager to meet and welcome him, just how durable the music he had made over 50 years before had proved to be. He died in 1983.