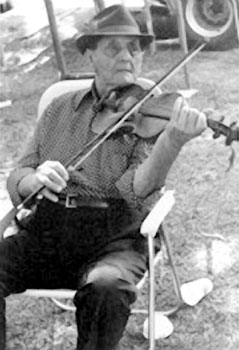

Dennis McGee and Sady Courville (FRC308)

by Jack Bond, Jean Stewart, Barry Ancelet &Tracy Schwarz

The tunes on this CD from the Field Recorders Collective were recorded in 1972 for release of an LP on Morning Star Records (LP #16001). That LP was released in 1972. Only twelve of the twenty-eight tunes played for the recording session were released on that album. The additional tunes, which have never before been released, are also included on this Field Recorders Collective CD.

In 1977, Richard Nevins released another LP on Morning Star (#45002) by Dennis McGee titled “The Early Recordings of Dennis McGee – Featuring Sady Courville and Ernest Fruge.” All of the tunes on that LP were originally recorded in 1929 and 1930. They include tunes with both Sady Courville and Ernest Fruge playing second fiddle. In 1929 and 1930, Dennis recorded eight tunes on the Vocalion label with Sady and seventeen on the Brunswick label with Ernest Fruge.

The Morning Star #45002 LP also contained a remarkable booklet about Dennis McGee, Sady Courville, and Ernest Fruge. Even though it was written for the 1977 LP, it is as relevant to the 1972 LP as to the 1977 LP. Just as fine traditional music should be preserved and made available to the public, so should fine writing about the music and the musicians who played the music be made available. Thanks to Richard Nevins for allowing the following articles to be included here. Some minor modifications to the articles have been made to remove information from 1977 that is not relevant today.

Dennis McGee and Sady Courville by Jean Stewart

The hands were what I noticed first about Dennis (they all say DenOOSE) McGee the day of our first meeting: enormous brown paws they are, that would seem to crush a fiddle if they even barely touched so small and slender a thing… Sady (Say-DEE or Suh-DEE, the Cajuns say) Courville later told us that he’d seen him cry sometimes, play the fiddle and cry at the sadness and I imagined the great crocodile tears, like those hands.

And they were never still: if we were sitting in a room and Sady and Bessie Courville or Leo and Eva Soileau were reminiscing about the old days, those hands could not have been more bored, they flexed and twitched and idled in his lap, played with the fiddle strings, the bow… I watched until I was sure their restless energy would burn itself out if it weren’t immediately yoked to the harness of that thin wooden box…

It of course never burnt itself out, else the 83-year-old man – tall, with the shoulder of an ox – would not have just returned from a grueling cross-country tour with Sady. That energy – apprehended by me long before our first meeting as I listened to tapes of his old recordings with Sady and Ernest Fruge, listened even to his recent Morning Star album with Sady and heard the same impassioned urgency (of bow biting into the strings) that I’d heard in his earliest recordings in 1928 – that energy has not deserted him, it’s the stuff of what his legend is built. “McGee don’t grow old,” he quipped when his old friend Leo Soileau first laid eyes on him after 10 years or more and kept saying how he hadn’t changed a bit…

The cultural context for that energy is easy enough: all the Cajuns I’ve met have it, to one degree or another. Not to romanticize them or their culture either, but look at their history, and then look back at the black slave story in America. Look particularly at the music that came out of the experience: gospel, bluesナcthe intensity of music that’s born of a collective outcast consciousness. Cajuns were outside the mainstream of American culture from the start, not only politically but culturally oppressed. Formal education was unheard of in the days of Sady’s and Dennis’ childhoods; Sady’s marvelously articulate wife Bessie remembers the first schools and what a breakthrough they represented for the much-scorned Cajuns, who were mostly regarded by white Anglo-Saxon Protestant America as crude illiterate heathens.

And the advent of schools was only the beginning. When I visited in April of 1975, the fight was well underway for the right to learn their own distinct and beautiful language in the schools, as opposed to English or Parisien French which is as different (in its idioms) from the richness of Cajun French as night from day. Sady recalls being punished more than once for lapsing into Cajun French in the playgroundナcIn those days even Parisian French would have been anathema in the classroom.

But it goes back much farther, to the earliest colonists from northern France who settled in Acadia, Nova Scotia, and devoted themselves with dogged persistence to their language, their culture, their Catholicism, their freedom. They had to, or lose it all in the welter of endless wars between France and Britain. England having won dominion over Acadia during Queen Anne’s War of 1713, the British were understandably alarmed at Acadians’ strong cultural identity. Oath after oath of allegiance was defied as the Acadians refused to bear arms against their French countrymen, refused to give over rich farmlands to the English, refused to feed British soldiers on their own precious fish, cattle, cornナcWhen in 1748 they again refused to swear the English oath, their lands and possessions were confiscated and their men deported while the women and children watched their homes burn.

During the next 11 years, the British continued to exile Acadians, more than 8000 in all, 4000 of whom died at sea of smallpox and other diseases. The survivors were scattered in major cities across the Eastern Seaboard and west in Canada and the States… In time, they found their way to Louisiana, where they were welcomed by the already-established French and Spanish Catholic population. They settled in the southwestern corner of the state with the blessings of the French governor.

The legacy then was contradictory: the old pride in “Cajun” (shortened from “Acadian”) had constantly to do battle with a powerful self-deprecating forceナcInevitably the substratum feeling was anger. Why should not such a people with such a history, have given birth to a wild impassioned music, indigenous to Cajuns and no one else, as escapist in its insistence on dance – one-steps, two-steps, waltzes, even polkas and mazurkas in the old days – as it was heartbreaking in its yearning? An angry music, issuing a challenge: I dare you to tamper with my joy.

And who indeed would dare to tamper with their joy! Not only is the old fiddle music itself at times almost unbearably intense (its energy level), but its practitioners are an intensively devoted band with something of a sense of “calling,” i.e., a sense of their music’s specialness. Canry Fontenot, the well-known Creole fiddler, tried to put it into words: “What I think makes our fiddle sound different is a special ‘crying sound.’ Like a baby. I remember how the old men used to shout at me, saying ‘Make it cry like a baby, Canry.’ Only Cajun or Creole fiddlers can do that. We do it by coming back on the high string and short of choking it as the bow rubs over it gently. I can’t say exactly how you do it, but I can do it. So can Mr. Dennis McGee and a few other old-time fiddlers.”

I like to think I know what he’s talking about, though it’s hard to see “gentleness” in the violent bowing – and yes, those high notes do sound like choking, like the fiddle’s being choked – fingers jammed between the bow-hairs and the wood and actually pressing out on the hairs to get their full tension. (Dennis sometimes plays with what looks like a full two inches between the hair and the wood, so taut is that bow! – which explains the force of his attack.) Certainly I know what he means by the “crying sound”ナcJust listen to the crying in Dennis’ voice. The degree to which a Cajun fiddle reproduces in its tone the Cajun voice is uncanny to me!

Dennis and Sady met in the mid-twenties. As it happens, they had much in common, starting with Gladys, Sady’s sister and Dennis’ wife. Both men were well-known musicians of the time, along with Amadee Ardoin, Angelais Lejeune, and Ernest Fruge, to name a few. Certainly they were among the most important and respected Cajun fiddlers of the day. For the next several years they played dances regularly, as had Sady’s predecessors, the Courville Brothers, before them.

Imagine how seductive, in those years immediately preceding the Depression, must have been the glitter of a cushy studio for a major for a major recording company in New Orleans. In 1929, they made their first recordings together, Dennis playing lead (melody) and Sady seconding. It was shortly after those early sessions – recorded only months after Joe Falcon went down in history as the first Cajun to record Cajun music – that Sady took what now seems an astonishing plunge: he gave up fiddle altogether, at around the same time that Dennis found another second in Ernest Fruge. His decision had only partly to do with the exigencies of a job conflict (the possibility of a comfortable career as a furniture-store merchant); the old ancestral shame in being Cajun was at least equally to blame. In fact at the time of the recording sessions, Sady requested of the company that his name be omitted from the labels when the records were released. And omitted it was: only “Dennis McGee” appears. It was the stigma: since the music embodied “Cajun” more dramatically than any other cultural form (except perhaps the language), it bore that stigma most directly. The sooner French Louisiana repudiated its native French-and-Canadian-influenced music and embraced instead the music of the dominant American culture (pop, country and western, bluegrass), the more convincing would be its people’s entry into mainstream America.

Sady didn’t touch the fiddle for 25 years. Dennis meanwhile was going strong: he recorded with the legendary accordionists Angelais Lejeune and Amadee Ardoin (1930) as well as with Ernest Fruge, a man of 31, born and raised in Eunice, who was regarded as one of the finest Cajun fiddlers alive. Ernest’s style differed subtly from his predecessor’s in one basic respect: while both men alternated long passages of melody on the bass strings (an octave below the lead) with a strongly rhythmic, rocking chordal effect, Sady’s bass line presented only the bare bones of the melody, in long sustained unadorned notes. The effect is of calm simplicity, in contrast to the intricate tapestry effect produced by Dennis and Ernest, whose seconding reproduces more closely the highly ornamented melodic line played by the lead fiddle, complete with cascading trill after trill. No dead space: every square inch filled. No rests – just as there are no rests in certain traditional music of say, Sweden and Norway. The resemblance in fact of this archaic Cajun twin fiddle tradition to the older style of fiddle-playing in central Europe is striking, especially with respect to those cascading rolling trills one on top of another, like overlapping folds of surf, neither ending or beginningナcThe similarity may or may not point to ancient origins for Cajun twin fiddling, of which Dennis McGee, Sady Courville, Ernest Fruge, and Leo Soileau were all masters. It’s a seductive idea, whether or not it has much historical credibility.

Both Sady and Dennis lived in Eunice, Louisiana, where Sady ran his furniture store and Dennis was a retired barber. The course of their lives gives one hope that their music will endure for, in spite of the rapid erosion of the old Cajun culture, they were a part of a handful of traditional musicians who recognized their roles as major carriers of the faith. In their later years, their performing schedule testified to that: they continued to play at a variety of festivals, including the National Folk festival, the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, and the folk festivals in Terres des Hommes, Montreal. For many years, Sady also participated in a weekly French radio program from Fred’s Lounge in nearby Mamou on KEUN in Eunice that was produced by Revon Reed. The programs featured Cajun music played by Sady, the Balfa Brothers, Nathan Abshire, and others. Without the efforts of those musicians and of such key members of the Acadian community as Revon Reed, accordion-maker Mark Savoy, lawyer Paul Tate, and the eloquently proud Bessie Courville with her sense of history – the traditional Cajun way of life and the music that so passionately embodies it would have long since passed from the sceneナc

Listen also to Morning Star’s album of Dennis McGee and S.D. Courville (#16001) and shake your head in amazement at the extraordinary vitality in the playing of these two men (then 80 and 68 years old respectively. (NOTE: IN 1994, Richard Nevins released a superb CD of Dennis Mcgee’s early recordings titled “The Complete Early recordings of Dennis McGee 1929-1930” on the Yazoo label – Yazoo 2012. The CD also contains a marvelous booklet that provides much additional information about Dennis McGee and Sady Courville).

The Words of Dennis McGee by Barry Ancelet

You will notice that the “words” of Dennis McGee are for the most part repetitive, from the point of view of ideas as well as vocabulary. It is almost always a matter of “You left me to go away – Say good-bye to your dad and mom, dear – Come on home to live with your man” – and the infamous Malheureuse (sadness, unhappiness). Mr. McGee, who made his fame in large part because of his song, does not really sing conventional songs. Rather, he sings complaints, that is, he sings complaints in song. There are no fixed words; everything is constantly moving, but within a specific framework of ideas and sensations that are particular to this singer. Thus these songs bear invariably the McGee trademark, but they do not differ more from one to another than does his situation from one time to another. This spontaneity contributes much to the force of this music.

Cajun Fiddle Characteristics by Tracy Schwarz

The striking differences heard in Cajun fiddling from other U.S. folk styles can be traced primarily to the use of the following noting hand techniques: drones, octaves, unisons, open strings with a lower tuning, slides, trills, and lack of vibrata. Briefly, these can be described this way: Cajun fiddling abounds in a ringing, sustained treble tone achieved by wide separation of notes played in harmony on adjacent strings. Where other fiddle styles lay in harmonies built mostly on thirds, the Cajun style persists in holding more separate on of the notes, making the appearance of octaves quite frequent and whenever possible, making one of the notes stationary by means of an open (untouched) string performing as a drone. The high (first and second) strings are most often used for this as well as with unisons, the technique of playing the same note on two adjacent strings, one of which is open. The already liquid effect is heightened further by the prevalent lower standard tuning DGFC. Rather than being cross-tuned, the fiddle is merely pitched one key lower to accommodate the C accordion found in most Cajun bands today, a solution entirely in keeping with the characteristics of the style.

Slides take place when a finger is pressed down on a string and slid up or down to the next note. This exists in other styles, too, but not in such a major role as Cajun fiddling. A trill happens when the player executes a rapid series of four notes, starting at A, going to B, then A again and then to G, and might be written this way: Vibrato is a very rare occurrence in Cajun fiddling. Whenever a note is sustained, the techniques mentioned in this discussion take the place of the vibrato’s embellishing function found in other folk styles. Simplicity and purity of tone are valued highly. It is as if the Cajun fiddler gets more of the potential out of each note this way. Bowing also contributes to this style, to a lesser but nevertheless important degree. This is best described in terms of the two-step, the waltz, and of the fiddling techniques used in seconding a lead fiddle. Old timers in the Evangeline country used to play such diverse dance tunes as the two-step, the one-step, the regular and two-time waltz (“Valse a Deux Temps”), Mazurkas, Polkas, and “Contradances Anglaises,” with even an occasional jig to be found. Today the two-step and the regular waltz seem to be the survivors; so here the two-step will cover everything not a waltz. The simple one note to one stroke sawing found everywhere is also done in the Cajun style, as well as playing two-note to one-stroke. In addition, a recurring series, or shuffle, is to be heard. Comprised of one long stroke followed by two short strokes, this link or section is joined to more of the same, forming the shuffle heard in the Nashville Country-Western scene during the 50’s. Indeed, Cajun fiddlers making their careers in the Country Music Capital could well have been the cause of its adoption there. In waltzes, the most strikingly different bowing technique is the marking of rhythm. Where country fiddlers will bow one continuous stroke to sustain a note, Cajun fiddlers change direction with each waltz beat, thereby providing rhythm alongside the melody. It mist be cautioned here that this is a general discussion and that personal observation of Dennis McGee and Sady Courville leads to the conclusion that older bowing styles were more complicated than this, and also that there are a number of different bowing sub-styles under the general title of “Cajun fiddling.”

Traditional old-time Cajun bands often included a lead and a second fiddle. An excellent representation of the style of Dennis McGee and Sady Courville appears on this Field Recorders Collective CD. As the techniques of the lead fiddle were distinctive, so were those of the second. The noting was usually on the lower, bass strings, and the bowing provided rhythm in three different ways: by simple “straight bassing,” i.e., slow pulling and pushing of the bow; by use of a “Nashville Shuffle” type of rhythm; and lastly, which is done so well here, by means of a rolling shuffle utilizing at least three, if not all the fiddle strings.