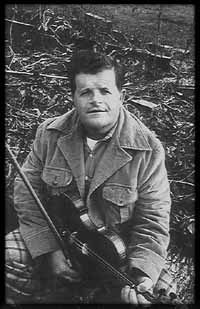

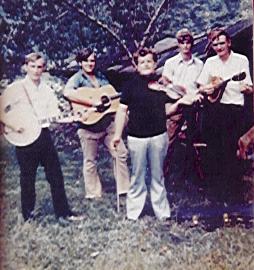

Buddy Thomas (FRC303)

by Mark Wilson

Biography and photos from Rounder CD0032, “Kitty Puss,” produced by Guthrie T. Meade and Mark Wilson.

Used by permission. To order Rounder CD0032, visit www.rounder.com.

We growed up real poor, so poor that even the poor folks said we were poor. There were ten in our family and we had to raise most everything we ate and work in logwoods and stuff like that. My dad worked all the time, but he was sick and had to doctor so much, that I don’t see how he could have made it if it hadn’t been for us. He was a big strong man until he got sick and he broke the record in Hoover’s time for loading fire clay. The company set out a five dollar gold piece for anyone who could beat Harve Thomas loading clay. He’d get up at three o’clock in the morning and walk to the mines, put in ten hours and come back home and cut wood of a night and do things like that to grow his family up. He had to be strong or else he couldn’t have stood all that he did. I’ve heard people say that on a winter’s night he’d pull off his bibbed overalls and they’d stand on the floor because of all the ice frozen on them. Dad believed in hard work and I had to work just the same as the rest of them. I couldn’t walk to do any good until I was eleven. I could hardly walk off the farm before I’d give out. My feet just curled over and a guy named Boone Morgan doctored me. He said I had rickets or something like that and he give me a bunch of what he called “Super-D capsules” and that got me straightened up. And my head never grew together right and when I’d get in the hot sun, my nose would bleed. Once it bled for four hours and fifteen minutes and I was nearly dead before they ever got me to a doctor. I’d be hoeing corn and my nose would get to bleeding, so I rest just long enough until it stopped and then I’d go on. In the summer, Dad’d get me up way before daylight and I’d go hunt the mules and we’d plow our corn, tobacco and cane. We’d come in for dinner and then go out and work up until dark again. Some nights we could hardly see to get back in. In the winter, we’d take old cross-cuts and go snake logs off the hills. Them was some good old days, though. It seems like that was my happiest days back then. A summer would never pass off so fast as when I was home under my dad’s thumb a-working. But now time just a-flies and I don’t know where a summer goes to.

When I got to walking pretty good, I started going down to the Rose school. I went there about five years, on and off, what little dab I did get to go. We had about four miles to go and we’d have to wade big snows and creeks to get there. My feet would get so cold that I could hardly stand it and it’d take forever to thaw them out. It was just a little old one-horse school, we called it, with one room. They had a class called the primer, then the first, second and third grades on one side and all the higher grades on the other. There were some of the awfullest looking big men in there you ever saw. They used to run off a lot of school teachers. I remember seeing the teacher and the big boys fight with boards and clubs and break out all the window lights and everything. Some of the teachers would get kids in there and like to killed them beating them up. This one teacher kept several big whips and paddles and he used to say that he’d shoot them all before he’d let them outdo him. He left his pieces of whip in one girl and they say she took to fits before she ever got home. Another teacher hit this girl in school and all these Bailey women hid alongside the road. When the teacher came along on his bicycle, they jerked him off and like to beat him to death. And his mother said she didn’t mind about them whipping him so bad, but they’d tore his new dollar shirt off of him.

When I got to walking pretty good, I started going down to the Rose school. I went there about five years, on and off, what little dab I did get to go. We had about four miles to go and we’d have to wade big snows and creeks to get there. My feet would get so cold that I could hardly stand it and it’d take forever to thaw them out. It was just a little old one-horse school, we called it, with one room. They had a class called the primer, then the first, second and third grades on one side and all the higher grades on the other. There were some of the awfullest looking big men in there you ever saw. They used to run off a lot of school teachers. I remember seeing the teacher and the big boys fight with boards and clubs and break out all the window lights and everything. Some of the teachers would get kids in there and like to killed them beating them up. This one teacher kept several big whips and paddles and he used to say that he’d shoot them all before he’d let them outdo him. He left his pieces of whip in one girl and they say she took to fits before she ever got home. Another teacher hit this girl in school and all these Bailey women hid alongside the road. When the teacher came along on his bicycle, they jerked him off and like to beat him to death. And his mother said she didn’t mind about them whipping him so bad, but they’d tore his new dollar shirt off of him.

It bothers me that I never had any education to speak of. I can’t talk up big in a conversation or place my words right or anything. When I was at the Smithsonian Festival, this TV guy came around and asked me all these big questions and I didn’t know what he meant. So I dodged him whenever I seen him coming. It makes it look bad on a guy to be on TV and not have any education. I don’t care a bit about something so long as I know what it means. A guy told me something the other day that made me feel real good. He said, “That little guy ain’t got any education, but he’s got more common sense than half the people through Carter County.” When I was small, I always wanted to be a carpenter when I grew up. A teacher named Carrie Duncan had me bring my fiddle to the school house one time and she told me, “If I were in your place, I’d practice and try to make my living playing fiddle.”

Sometimes of a night the old-timers would come visit and I’d lie in bed and hear them tell stories about killing bears and haunted houses and stuff like that. And they used to talk about all these mad dogs that were going through our country. This one guy got bit and seven years later he got to feeling funny. He told his wife to take the children to her daddy’s, he believed he was going mad. And he made her tie him to the bedposts. She slipped back to look in the window and he was biting himself and the blood was just a-running from his arms. He got loose that night and they found him dead later, with all the meat chewed off his bones. A mad dog came through our country and bit a black-and tanner of mine. Its eyes got real green and it’d eat up cardboard boxes like they were bread, so my dad had to shoot it. My mother would get so nervous over the mad dogs that she slapped planks over all the windows. There for a long time we’d hardly get out of the house. They used to say that the only thing that could cure it was a madstone. They would put that on the bite and it would draw out the rabies.

That was about the time I heard the baby a-crying. There’s a big rock cliff around by this cemetery near home and back in the olden days they used to see all kinds of signs and wonders there. There’d be horses running past you and they claimed you could hear them but never see anything. Lit Darr used to ride a big black horse past there and one time he said a shadow like a large person got on behind him and it was so heavy that the horse could barely walk. They went so far and then the shadow got off. I believe Lit Darr told the truth about that. He was an awfully good old person. And then Vestner Fannin said he was going through there one moonshiney night and there was a guy just running back and forth in the timber. He asked who it was and nobody even answered. He knew right then it wasn’t anybody a-living. I never did see anything except that one time when I was small. My brother got me up way late at night to hear this little baby crying – Lord, it’d make cold chills run over you to hear it screaming. Dad took two dogs that could run anything, but he never come across a thing. They say that this baby has been heard down there for years. Everybody figures that there’s been some people murdered down there in those rock cliffs.

I walk around these ridges at night yet. I know every inch of the way practically, but I still get the chills whenever I go over by that cemetery. A guy tried to kill me there once. I passed by this car that was all covered with brush and I noticed this guy following after me in the dark places under the trees. I picked me up two big rocks and walked backwards up the hill. I said, “If you come any nearer, I’ll beat out every brain you’ve got.” When I got up to this spot I knew, I took up that hill just like a fox. And this guy came running up the main road looking for me. I always figured it must been somebody loading moonshine and they were going to make sure I didn’t tell anybody.

I walk around these ridges at night yet. I know every inch of the way practically, but I still get the chills whenever I go over by that cemetery. A guy tried to kill me there once. I passed by this car that was all covered with brush and I noticed this guy following after me in the dark places under the trees. I picked me up two big rocks and walked backwards up the hill. I said, “If you come any nearer, I’ll beat out every brain you’ve got.” When I got up to this spot I knew, I took up that hill just like a fox. And this guy came running up the main road looking for me. I always figured it must been somebody loading moonshine and they were going to make sure I didn’t tell anybody.

There are people down there who don’t care for anything: they’ll kill you for ten dollars or steal you blind or anything. In the olden times, they used to have a temper awfully bad. My grandfather Thomas went plumb crazy and killed seven men. And Marion Stamper killed seven men too, with one rifle. All these Stampers and Underwoods were into it over stealing horses. When Joe Stamper was just a little boy, these Underwoods would hide in the woods and shoot at him when he was plowing in the bottom. He’d plow out a little bit and they shoot at him. Once they shot his plow handle off and he decided to go back into his house that time. Marion Stamper gave that rifle to my dad’s uncle and every time Marion Stamper came over, he’d call for that gun. He wouldn’t get off his horse or anything and they said, at certain times, it’d look just like there was blood on that gun.

The banjo was the first thing ever I started a tune on. My parents both played in the old overhanded style and they’d play “Roll On, John,” “Sourwood Mountain,” “The Blue Rooster” and different stuff like that. My mother could play the organ and sing old songs like “Stella Kinney” and “The Rowan County Troubles” and one about a little sparrow. They used to say that she was about the best organ player for backing a fiddle tune through our part of the country. But they didn’t have much time to play because they worked so hard and went to bed early. Back when my dad was a-living and before my brother got killed, they always had old banjos and stuff like that around the place. I learned to play all sorts of different instruments, but after they passed away, we never did have any, so I just stuck to the fiddle. I never learned to sing any; I always felt like a mule a-eating briars when I did. One time this guy from just over the Lewis County line made one of these dulcimores out of old orange crates. I thought it would be real hard and so I traded him this little old fiddle I had. But in fifteen minutes I could play it just as good as he could and I wished I had my fiddle back again.

The first time I played a fiddle was when my brother got hold of this old homemade violin. He told me, “I dare to catch you with that fiddle and I’ll give you a good beating for it.” I wanted that little fiddle so bad I was sick. When they went off to church, I got me a box and chair and climbed up to get it. When my brother came back, I was already starting a tune and my dad made him let me use it then. I learnt the best part of my tunes from my mother whistling the tunes that my grandfather, Jimmie Richmond, used to play. The first one I learnt was “Cluck Old Hen.” She knew what key to start them in and could put in all the double time notes with her whistling. All her family were good whistlers and they used to win all the whistling contests that they had thought through our part of the country. There weren’t hardly any other fiddlers around when I was growing up, only Perry Riley and he’d just come through every once in a while. He’s my second cousin on my mother’s side. He worked in West Virginia and Arkansas a lot and he’d go away and nobody would even know whether he was dead or alive. Once when I was a boy, it was fifteen years before we ever saw him again. Back then we never had any radios and the only way I had of picking up any tunes was from my mother’s whistling. Then she started going to church and singing hymn songs and that kindly left me a-wondering where to learn my fiddle tunes.

The first time I played a fiddle was when my brother got hold of this old homemade violin. He told me, “I dare to catch you with that fiddle and I’ll give you a good beating for it.” I wanted that little fiddle so bad I was sick. When they went off to church, I got me a box and chair and climbed up to get it. When my brother came back, I was already starting a tune and my dad made him let me use it then. I learnt the best part of my tunes from my mother whistling the tunes that my grandfather, Jimmie Richmond, used to play. The first one I learnt was “Cluck Old Hen.” She knew what key to start them in and could put in all the double time notes with her whistling. All her family were good whistlers and they used to win all the whistling contests that they had thought through our part of the country. There weren’t hardly any other fiddlers around when I was growing up, only Perry Riley and he’d just come through every once in a while. He’s my second cousin on my mother’s side. He worked in West Virginia and Arkansas a lot and he’d go away and nobody would even know whether he was dead or alive. Once when I was a boy, it was fifteen years before we ever saw him again. Back then we never had any radios and the only way I had of picking up any tunes was from my mother’s whistling. Then she started going to church and singing hymn songs and that kindly left me a-wondering where to learn my fiddle tunes.

They said my grandfather Jimmie Richmond was about as good as they had back in those parts. Mother said his hoedowns were peppy and you could dance to them good. She said a lot of people you hear play nowadays don’t put any life into their tunes and that a lot of times they play too fast. She likes to hear all the bowing put into a tune. I remember seeing my grandfather just a couple of times when I was real small. He was about seventy-five years old and he had a big white mustache. When he got drunk, they said he didn’t care about anything. He would drink whiskey and sit on the rail fence out in big rainstorms and things like that.

They had a lot more dances and fiddling back in those days. There was a girl who lived around Concord, Kentucky and she held a fiddling contest for all the single guys – whoever played the fiddle the best got to marry her. And this old guy named Dick Swinington won and she married him. After he passed away, she would go by their old house most everyday and call out, “Dick, are you in there? If you are, just saw three times across your old fiddle.” One time a bunch of young guys hid in the house with a fiddle and they sawed away when called out like that. She ran away and never went back to that house no more.

There was another old guy named George Cole who used to walk up and down the roads playing the fiddle; I guess he was kind of simple. Bob Glenn came through from West Virginia – and he heard George Cole a-playing. Bob said, “That guy plays some of the prettiest notes to not play anything I ever heard.”

And George followed Bob Glenn up to Portsmouth and he came back and told everybody: “You know that Glenn feller you were telling me all about? Well, we had it out and I edged him.”

One time a bunch of fellows were sitting at the general store and one of them gets to growling like a dog to scare old George into thinking he had been hit by a mad dog. And so he starts chasing old George up the road, growling and biting at him. This other guy named Mock let on like he was trying to catch them. George looks back and says, “Catch him, Mock, he’s a-gaining on me.”

Mock yelled back, “I can’t.”

“Well, speed up a little bit,” says George. Of course he didn’t care whether Mock got bit or not.

They used to have big fiddle plays in theaters and different places around Portsmouth, Ohio. Bob Glenn, Clark Kessinger, Ed Haley, Asa Neil and all those guys used to play there all the time. A couple of friends of mine played a show up there in Ohio way before I was born. The banjo player got drunk and lost his picks in the spittoon and hunted them out in front of everyone. The audience started booing and ran them off the stage. This other musician came on and was getting a bigger hand, so the fiddle player got a big bucket of water and threw it over the curtain on him. Then they both ran away and came back to Kentucky.

A lot of my fiddle tunes I learned from Morris Allen up there in Portsmouth. He’s getting near eighty but he’s still a pretty good old fiddler. Back in the thirties, he was a bachelor and had a good job in a steel mill and he used to like to get all the fiddlers together. His uncle John Kiebler was a real good fiddler and Clark Kessinger would come stay at Morris’ house for a week or two. I first met him when I was out fox hunting. Morris had lost some dogs and he had his fiddle with him. And I then got to hearing him and different good fiddlers around Portsmouth and the fiddle sounded so pretty that I just had to get into it and learn those tunes. Then Sam Cox told Jimmy Wheeler about me. He said, “It’s a young fiddler out there a-growin’ up that knows parts of them old tunes. You ought to go out there and kindly help him out.” And so Jimmy came up and made me a tape.

About half the time I wouldn’t have a fiddle and I’d have to go over to somebody’s house to practice. If I was supposed to someplace to play, I’d go over the night before and stay all night working on it. I’ve been going up into Ohio ever since I left home at nineteen. I would play bluegrass and stuff like that in bars and I was all the time telling all kinds of jokes to make people laugh. They called me “The Macon Man” and said it looked like I had been eating watermelons down South. A lot of them used to get jealous of the musicianers – “You think you’re smart ’cause you plays,” and they’d call us hillbillies. I didn’t pay any mind to that because it got so that you heard that just about everywhere you went. One time I stayed drunk for two weeks up there. I never slept any, just a-fiddling and drinking the whole time. But I never bothered anybody when I got drunk and I never got into any fights either. Anytime somebody would jump on me, There’d be three or four others into it. I guess I was always pretty well protected.

When I was working in the factories up there in Ohio, I’d hardly play at all. You wouldn’t feel much like playing when you had to get up at six in the morning. I used to go as high as a year at a time and never play a tune. I could never pass any physicals from a doctor. The way I’d usually have to get my factory jobs was to get in with somebody in personnel. I was playing one time in Ohio and this banjo player was a personnel manager at a rubber company. He asked, “How long are going to be around here, Shorty?”

I said, “I’m leaving out in the morning.”

“Why are you leaving?” he said, “We’d like to have you around to play with.”

I told him that I would be broke in a few days and had to get back home but he said he’d get me a job. I told him about the physicals but he took me to the office and fixed my papers up. And I stayed there until my mother got sick and I had to come back home. You can’t hardly get a good job in Kentucky unless you’ve got a good education. So I’ve just gone to farming and snaking logs off these hills to get by. Then they’ll come all times of day and night to get me to play fiddle. It gets so bad sometimes that I have to tell that I’m not at home. A bunch of us boys might take two or three gallons of moonshine, several cases of beer and spend the whole weekend, fiddling and carrying on. We might go back over into Ohio someplace and stay a week before I have to come back to see how Mother is doing because she’s all alone on the ridge when I’m away. Or we’ll get under rock cliffs, build up big fires and fiddle. Maybe we’ll have a fox chase. Sometimes they’ll fight and get into big rackets over which one’s dog is in the lead, but I think it makes a prettier chase when you’ve just got six or eight hounds out. Then it’s just like listening to a bunch of fiddle tunes to hear those dogs run. And it seems like I can remember a lot of those old tunes quicker when I’m out there a-drinking. I’ve studied more about fiddling in these last few years just remembering the way my mother used to whistle to me. I’d never forget anything that I heard back in my childhood like that. Most people down here just like to hear the bluegrass and stuff like that now, but I like the old-timey tunes because it seems like they got a lonesomer sound.

I told him that I would be broke in a few days and had to get back home but he said he’d get me a job. I told him about the physicals but he took me to the office and fixed my papers up. And I stayed there until my mother got sick and I had to come back home. You can’t hardly get a good job in Kentucky unless you’ve got a good education. So I’ve just gone to farming and snaking logs off these hills to get by. Then they’ll come all times of day and night to get me to play fiddle. It gets so bad sometimes that I have to tell that I’m not at home. A bunch of us boys might take two or three gallons of moonshine, several cases of beer and spend the whole weekend, fiddling and carrying on. We might go back over into Ohio someplace and stay a week before I have to come back to see how Mother is doing because she’s all alone on the ridge when I’m away. Or we’ll get under rock cliffs, build up big fires and fiddle. Maybe we’ll have a fox chase. Sometimes they’ll fight and get into big rackets over which one’s dog is in the lead, but I think it makes a prettier chase when you’ve just got six or eight hounds out. Then it’s just like listening to a bunch of fiddle tunes to hear those dogs run. And it seems like I can remember a lot of those old tunes quicker when I’m out there a-drinking. I’ve studied more about fiddling in these last few years just remembering the way my mother used to whistle to me. I’d never forget anything that I heard back in my childhood like that. Most people down here just like to hear the bluegrass and stuff like that now, but I like the old-timey tunes because it seems like they got a lonesomer sound.

Different times I’ve thought about quitting. One old guy said that if he were in my place, he’d stop fooling with the fiddling. He said it was the Devil’s work. And I thought to myself that the Devil’s got some pretty good work cut out for him if he’s going to learn to be a fiddler. All the Baptists go on what they read in the Bible: that you’re allowed to have music in your own house. But I would always play any place anybody wanted it. As long as people liked to hear me, I’d go play. And just here the other day, Mother told me that I played closer to her daddy than anyone ever she heard.