By Howard (Rusty) Marshall

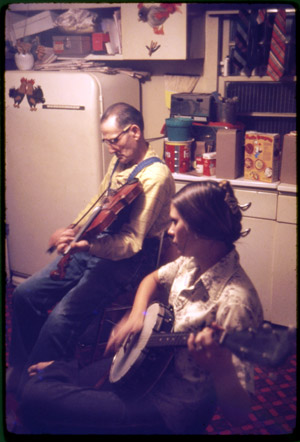

On a chilly, clear evening in November 1975, I had the opportunity to record and photograph the fiddler Lee Roy Stoneking at his home in Clinton, Missouri, a few miles from the farm where he was born. Stoneking had invited his son, Fred, to come play backup guitar, but Fred couldn’t make it. But his daughter, Judy Vanderville, was handy, and the session turned out nicely, with just Lee playing tunes on one of the twenty-five violins he had made in a room off the kitchen, and his charming daughter accompanying him on old-time finger-style banjo [Judy (nee Vanderville) Champagne told me that she’d just come back from a long bicycle ride and wasn’t particularly in the mood to play music at the moment, but of course her father’s “request” was obeyed! -Lynn Frederick]. As the hours grew late, Judy sang a few country songs with Lee’s fiddle accompaniment. Along with hearing some fine music and stories, I enjoyed the kind of gentle hospitality and trust accorded to strangers for which the rural and small town Midwest is famous.

That session was recorded during a trip back to Missouri on brief assignment from my colleague, the inimitable Ralph Rinzler, to visit and record a sampling of Missouri fiddlers who might be invited to perform at the Festival of American Folklife on the Mall in Washington the following July. In 1975, I was living in Noblesville, Indiana, and employed at an outdoor museum called Conner Prairie Pioneer Settlement, and spending most of my nights trying to finish my dissertation under Henry Glassie at Indiana University; my mind was focused on old buildings and tangled theories, but I couldn’t resist Rinzler’s request that I do a bit of field recording of Missouri fiddlers. Other fiddlers I recorded on that trip in November 1975 included Art Galbraith, Glen Rickman, Taylor McBaine, and Lonnie Robertson. I also provided Rinzler’s office at the Smithsonian with several home recordings and vanity-press LPs of Cyril Stinnett, Jake Hockemeyer, Lyman Enloe, and Pete McMahan - among other fiddlers I had planned to visit. I believe that the reel-to-reel tapes and photos are archived at the Smithsonian.

In the Seventies, the variety and richness of Missouri fiddling was not appreciated or well understood by outsiders - or even by many researchers within the state itself. Most researchers were focused on Appalachian-derived styles, survivals of ethnic styles, etc., that comfortably fit the seminar preconceptions. I was told, on different occasions by some of the folk arts and festival leaders of the Seventies, that Pete McMahan’s fiddling and Cyril Stinnett’s fiddling, for example, were considered “too good.” Similarly, Lee Roy Stoneking’s playing was almost too smooth and sophisticated for the tastes of some of the mostly city-born folk music experts and festival staffs of that era, who, as were many professionals of the Folk Song Revival era, more interested in pointing cameras and recorders towards the apparently most backwoodsy and stereotypical “folk” in their field research. The air was thick with arts council grants and Bicentennial fervor for quilts, pottery, baskets, polka bands, blues and barbecue. Moviegoers thought Ozarkers were really like The Beverly Hillbillies (1962-1971), that Tennesseans were really like the characters in 1972’s Deliverance. We folklorists and anthropologists and semioticians and ethnomusicologists recorded it all and shook it all through the very fine screens of French structuralist theory. The jargon got out of hand. People became informants. Woody Guthrie (d. 1967) and Francis O’Neill (d. 1936) rolled over in their graves.

Wait, where was I? Oh. Informants (I still dislike that word) of the era initially were bumfuzzled if not amused by all the attention. But they figured it out that, if they were to receive an invitation to a festival, it would behoove them to speak of their fiddling as stemming from ancient rhythms and melodies handed down from rustic forbears rather than music influenced and sweetened by the contemporary culture around them. But we suppose that a festival cannot easily convey complexity, that the snapshot and stereotype can sometimes work as the starting place for appetite whetting and fuller understanding; in fact, fuller understanding is what those of us who hosted festival workshops tried to encourage when we presented, say, a fiddler who appeared to be the iconic hillbilly but who, in their formative years, turned out to have listened to Joe Venuti and Eddie Lang 78s.

From Chilhowee (Johnson County), Lee Roy Stoneking was of Scottish, Irish, English, and Cherokee ancestry, and from a long and full line of dance fiddlers, musicians, and singers. While farming families like the Stonekings had telephones, electricity only reached their homes in the 1940s. Like many other fiddlers, Stoneking began as a youngster playing “rhythm” and accompaniment for other fiddlers, and enjoyed playing old-time banjo. He learned to play fiddle tunes in the manner of those close to him, particularly his uncle, Frank, and his four other fiddling uncles, Jake, Price, George, and John Stoneking — all good players who played at local dances and sessions. In addition, Lee’s mother played old-time finger-style banjo (parlor style) and fiddle, as well as piano and reed organ.

The familiar accompaniment for many Missouri fiddlers of the time (early twentieth century) was piano and reed organ, as well as banjo (a parlor style, a version of down-stroke frailing, or a version of today’s melodic claw-hammer style). The “bass” in early Missouri string band music was most often a bowed cello. Guitar accompaniment became more popular during the 1930s and 1940s.

At the same time, Lee was listening to records, radio programs, and traveling to fiddle at dances in his area of west-central Missouri. His repertoire well echoes all these influences and more. While he did not consider himself a “contest fiddler,” Stoneking competed in numerous contests within Missouri and beyond, and often came away high in the rankings. During the heated era of fiddlers’ contest promotions and establishing of fiddlers’ associations in the 1960s and through the 1970s and into the 1980s, Lee Stoneking’s slow and stately fiddle style began to sound dated to some of the new audiences and judges whose brains were being re-wired by the steadily-expanding lava flow of Texas-based contest style (aka “Weiser style”). A dozen or two contest tunes were made an international fad by Mark O’Conner and a few other influential players, and there was the popularity of post-Bonnie and Clyde and Deliverance bluegrass that tended to stress speed and hot licks. But that’s another story for another time.

Lee Roy Stoneking and daughter, Judy Vanderville, Clinton, Missouri, November 1975. Stoneking is one of very few fiddlers in my experience who held the violin “down” on his chest. (Photo by Howard Marshall, reproduced in “Play Me Something Quick and Devilish:” Old-Time Fiddlers in Missouri, University of Missouri Press, 2012)

To the interviewer’s familiar query about how the fiddler would describe his or her style, Lee liked to call his style, inherited in part from his father, Frank, “listening music.” As a young grad student (from a small-town family of fiddlers, pianists, and opera singers) trying to figure out what styles meant in fiddle music, this “listening music” formulation was interesting and helped me understand Lee Stoneking as an individual player with a personal style. We might well situate his music (in style and repertory) in categories such as “old-time,” “bluegrass,” and “country.”

But, like so many fiddlers I reflected upon on through the ensuing decades, to me Lee Stoneking was in his own category. In fact, most of the other fiddlers I had recorded on this field trip for the Smithsonian were individualistic too, while, at the very same time, they were capable of being given a broad stylistic label. Two examples: Lonnie Robertson is thought of as an Ozark fiddler, but his music and his career easily show us the influences of everything from Lowe Stokes records to The Monroe Brothers (Bill and Charlie), popular dance music and ragtime, and especially to the melody-driven, hornpipey (now there’s some jargon!) music he absorbed from fiddling over radio shows in north Missouri, Iowa, and Nebraska with Casey Jones and Bob Walters. When I asked Taylor McBaine (Columbia) his style at his in Columbia in 1975, he reared back and smiled, “Boone County Style!” Yet the broad categories are useful considering cultural personality and differences tied to such things as place, family heritage, and intention. If pressed to place Lee Stoneking in one of the major Missouri categories (Missouri Valley / North Missouri; Little Dixie / central Missouri; Ozark), Little Dixie would be it.

So one might suggest that this is where Lee Stoneking’s fiddling, especially in repertoire and also in performance style, fits: old-time central Missouri style of what more and more I choose to call, “the smooth school of old-time fiddling.” Like his peer, Lyman Enloe, several old-timers I knew referred to Lee Stoneking as “old smoothie.” One can hear why, in the historic recordings provided by Linda Higginbotham and Brad Leftwich for this Field Recorder’s Collective project. Another feature I admire in Stoneking’s style is conscious preference for a rather slower and more lilting pace in playing tunes, even breakdowns for square dancing but especially his two-steps. Lee was unusual in his predilection for playing more slowly than his peers or even his uncles. And he played “clean,” a key characteristic in the evolving bluegrass and contest fiddle styles of the Sixties and Seventies.

Several of Lee Stoneking’s versions of tunes have become standards among fiddlers in Missouri, including “Virginia Darling,” “Old Indiana,” and a foxtrot (two-step) called “Echoes of the Ozarks.” Stoneking played with such grace and flowing clarity that others could, with a bit of skill, acquire tunes from his appearances and the self-produced LPs he released in the 1970s.

“Echoes of the Ozarks” has an interesting and still incompletely understood backstory. My current research suggests that “Echoes of the Ozarks” may now be credited not to Stoneking but to Ishmael (Ozark Red) Loveall of Linn Creek (Camden County), a popular fiddler Lee Stoneking, Lyman Enloe, Art Galbraith, and other well-known Missouri fiddlers heard at contests and over live radio programs in the 1940s on Springfield’s KWTO AM. (Lyman Enloe’s version of Red Loveall’s “Raking the Leaves” - a rare tune — is available on the compilation CD with the 2012 book, “Play Me Something Quick and Devilish.”) An outstanding and versatile old-time and swing fiddler of the 1930s and 1940s, Loveall found success in swing and cowboy music ensembles on several radio stations in Missouri and southern Illinois. Then, following hints from the musicians’ grapevine, Loveall decamped to San Francisco in the late 1940s, where he became a popular radio fiddler and personality as well as a recording artist, making several well-received country records with singer Rusty Draper, another ex-patriot Missourian who went West.

Red Loveall’s title for “Echoes of the Ozarks” may have been “Echoes of the Hills,” which is the title Lyman Enloe remembered from a 1939 fiddlers’ contest in Bagnell, Missouri, where he heard Loveall fiddle it. In the 1980s, Pete McMahan helped further spread the tune as “Echoes of the Ozarks” and played it in B-flat (rather than D or G). McMahan often said he learned the tune from Lee Stoneking, but decided the tune worked better for him (McMahan) in B-flat, and McMahan’s many years of influential fiddling are most important in the spread of the tune among Missouri fiddlers. To the delight of many and chagrin of others, McMahan delighted in moving dance tunes and even breakdowns to the keys of B-flat and F, the better to compete with his B-flat and F loving contest rivals such as George Morris and Ed Tharp, powerful competition players of the 1940s and 1950s. (Indeed, the Columbia area and Little Dixie writ large have long been infamous as a region where the most respected fiddlers revel in, or at least can manage, “the flat keys” of F and B-flat. I can remember otherwise smart fiddle scholars trying to convince me that if a fiddler played in F or B-flat, he or she certainly was not a “real” fiddler.) Red Loveall will appear in the sequel to “Play Me Something Quick and Devilish.”

Moreover, the Columbia swing fiddler, Luther Caldwell (d. 1969), played a version of “Echoes of the Ozarks” in the 1950s under the title, “Traveling Back to Dixie,” which he had learned from Fulton / Columbia fiddler Ed Tharp. Bill Driver’s 1940s version as “Echoes of the Ozarks” is transcribed in R. P. Christeson, The Old-Time Fiddler’s Repertory (1973, p. 178, key of D), and before that a version appeared in the Ira Ford 1940 book called Traditional Music of America (p. 123, key of G), and it is possible that the Missourian, Ford, heard either Lee Stoneking or Red Loveall play the tune. Other tune books include the tune as well, including Drew Beisswenger and Gordon McCann’s marvelous project, Ozark Fiddle Music (2008, p. 90, key of G), where a 1926 version from Sam Long is offered (said to be the first commercially-recorded fiddler with Ozarks connections).

The “Echoes of the Ozarks” / “Echoes of the Hills” melody may go back to a pre-Civil War minstrel song, or perhaps a cakewalk. It is also redolent of country rags of the early twentieth century. The tune was spread into the Dakotas by Lee Stoneking, Fred Stoneking, and Pete McMahan, who played it at the Yankton, South Dakota, fiddlers’ conventions and contests in the 1970s (Lee) into the 1980s and 1990s (Fred and Pete). As a regular participant or judge at the Yankton events from the early 1980s until very recently, I’ve heard “Echoes of the Ozarks” become a favorite among Northern Plains fiddlers. The love of the northerners for the two-step is reflected in their playing it appropriate to this couple dance. In my opinion, Lee Stoneking’s “Echoes of the Ozarks” is the finest recorded version of this great Missouri tune, in part because he lets the music breathe and makes it very danceable. Lee also played “Turkey in the Straw” that way - as a two-step (issued on one of Wilbur Foss’s Yankton event sampler cassettes in the 1990s). No doubt the use of the word “Ozarks” in the title, rather than the word “Hills,” adds to the appeal of the tune for many people. Whatever title you prefer, fetch out your musical instrument and give it a whirl. All I ask is that you think “two-step” instead of “hoedown.”

Lee died in 1989, but Stoneking music continues. For a good many years, Lee’s son Fred carried it forward to new audiences and aficionados, until his death in 2009. Fred Stoneking was among the most outspoken and patriotic of Missouri fiddlers, and devoutly promoted his take on traditional fiddle and accompaniment through his many festival appearances, fiddle camps, recordings, and contest appearances. Like many of us, Fred absolutely knew what “real” old-time fiddling and fiddle accompaniment should be: that fiddling and accompaniment style inherited from his father, Lee, and his uncles and other family members, neighbors, and picking buddies. Fred was particularly adamant about keeping alive the old-time straight-chord Missouri guitar accompaniment style that has been under siege from the modern, contest style, swing and closed-chord jazz-derived guitar accompaniment. Fred, like his father Lee, liked all kinds of music (yes, even bluegrass! and western swing!), but when the chips were down at a fiddlers’ contest or teaching his music at camps like The Festival of American Fiddle Tunes in Port Townsend, Washington - or with an arts council administrator or folklorist present - he was all business about the importance of keeping one’s family and regional traditions alive and well. On numerous occasions, I recall how Fred would be sure his daughter, the gifted guitar accompanist (and fiddler) Alita, was going to play it “straight” and “old-time” when they got up the microphone.

The family legacy is in capable hands today, with Lee’s granddaughter / Fred’s daughter, Alita Stoneking Weisgerber. While not currently in the fiddle and dance scene, Alita’s younger brother, Lucas Stoneking, is also a talented fiddler. For some years, I have regarded Alita as one of finest fiddlers I have ever heard, whether listening in on a hot Texas-style jam session or perched on a folding chair at the judges’ table in front of her at a contest. Alita now lives in southern Minnesota with her National Champion fiddler husband, Tom Weisgerber, and she offers an interesting case of a brilliantly talented young woman who can play at a high level both the older, inherited fiddle tunes and guitar accompaniment style of her family and region as well as today’s influential National Contest (Weiser) style of fiddle and guitar playing. Alita has won numerous fiddle titles across the nation, and is a favorite guitar accompanist for fellow competitors. It is good to know that, while Alita Stoneking Weisgerber may perform the internationally-popular fiddle contest style and repertoire, she is of such intelligence and depth that she also carries on the old-time music of her central Missouri family.

I’m delighted by the efforts of Brad Leftwich, Linda Higginbotham, Lynn Frederick, and their colleagues, to bring out this amazing collection of great tunes by one of Missouri’s most interesting fiddlers of former times, Lee Roy Stoneking. Thank you! And thank you for asking me to share my memories and impressions of Lee Stoneking in his time and place; a recorder of stories, I suppose I am now telling the stories, too. And so it goes.

Howard Wight Marshall

Professor Emeritus

Dept. of Art History and Archaeology

University of Missouri

Columbia, November 14, 2014

Additional information and links:

- Marshall, Howard Wight, Play Me Something Quick and Devilish: Old-Time Fiddlers in Missouri. University of Missouri. 2013. Includes CD. More info here.

- Beisswenger, Drew and McCann, Gordon, Mel Bay presents Ozarks Fiddle Music. Mel Bay Publications, Inc., Pacific, MO. 2008. More info here.

- Stoneking, Fred, “Recollections of a Missouri country fiddler.” From insert notes of the CD Saddle Old Spike: Fiddle music from Missouri – Fred Stoneking, on Rounder CD 0381. Reprinted here.

- Brennan, LaDon, “Lee Roy Stoneking” online memorial including family information and discography of privately released recordings. View memorial page here.

- Thanks to Alita Weisgerber, Jim Nelson, Charlie Walden, Howard Marshall, Dan Gellert, Geoffrey Seitz, Kerry Blech and Paul Wells for helping us with tune identification.