FRC718 – Carlton Rawlings – Bath County, Kentucky Fiddler

by John Harrod

INTRODUCTION

Northeastern Kentucky was still a hotbed of old style fiddling in the 1970s and ’80s when Gus Meade, Mark Wilson, Bruce Greene, and I began making regular visits to record and learn from the many interesting local fiddlers who were still going strong at the time. We were astounded at the sophistication and complexity of the styles, the level of performance, and the dramatic intensity of the playing. Rather than the last faint echoes of a dying tradition hinted at by a few old fiddlers well past their prime, here was a regional fiddle culture still intact, conscientiously (and often competitively) nurtured by its proud practitioners and recognized and valu

ed by their community. This culture included banjo, guitar, harmonica, and piano accompanists as well as avid step dancers and square dancers.

The local fiddler best known to the wider world, outside the four or five county area that was the center of this activity, and the first one I became acquainted with was George Le

The local fiddler best known to the wider world, outside the four or five county area that was the center of this activity, and the first one I became acquainted with was George Le

e Hawkins. George had been recorded at Renfro Valley in 1946 by Malvin Artley and had a reputation as a hornpipe player from his appearances at fiddle contests throughout the eastern half of the state. Through George we met many others, including Alfred Bailey and Henry York, and began to hear stories of the renowned fiddlers who had preceded them, such as Tom Riley

and Hiram Humphreys.

Years passed and by the mid-1990s all the great fiddlers of this era had passed on, and we were left to wonder what, if anything, might survive of this once great fiddle tradition. The series of recordings on Rounder that had been initiated by Gus and Mark and continued by Mark and me after Gus’s death had introduced the world to Kentucky fiddling, but we were never confident that what might be transmitted to New York or Seattle could ever faithfully represent the feeling, the places, the personalities, and the history that made the music what it was. Deeply attached to the individuals we had known, and seeing the places where they lived changing before our eyes and turning away from the past, we began to feel that we had indeed seen the end of something that could never be regained. But gradually a new path revealed itself in the discovery of older home recordings of some of the same individuals we had recorded, as well as others who had died before we came along. Subsequent years proved this to be a fruitful path of inquiry, as I discovered more and more lost recordings of individuals who heretofore had only existed for us as names, sometimes almost legendary, from the past.

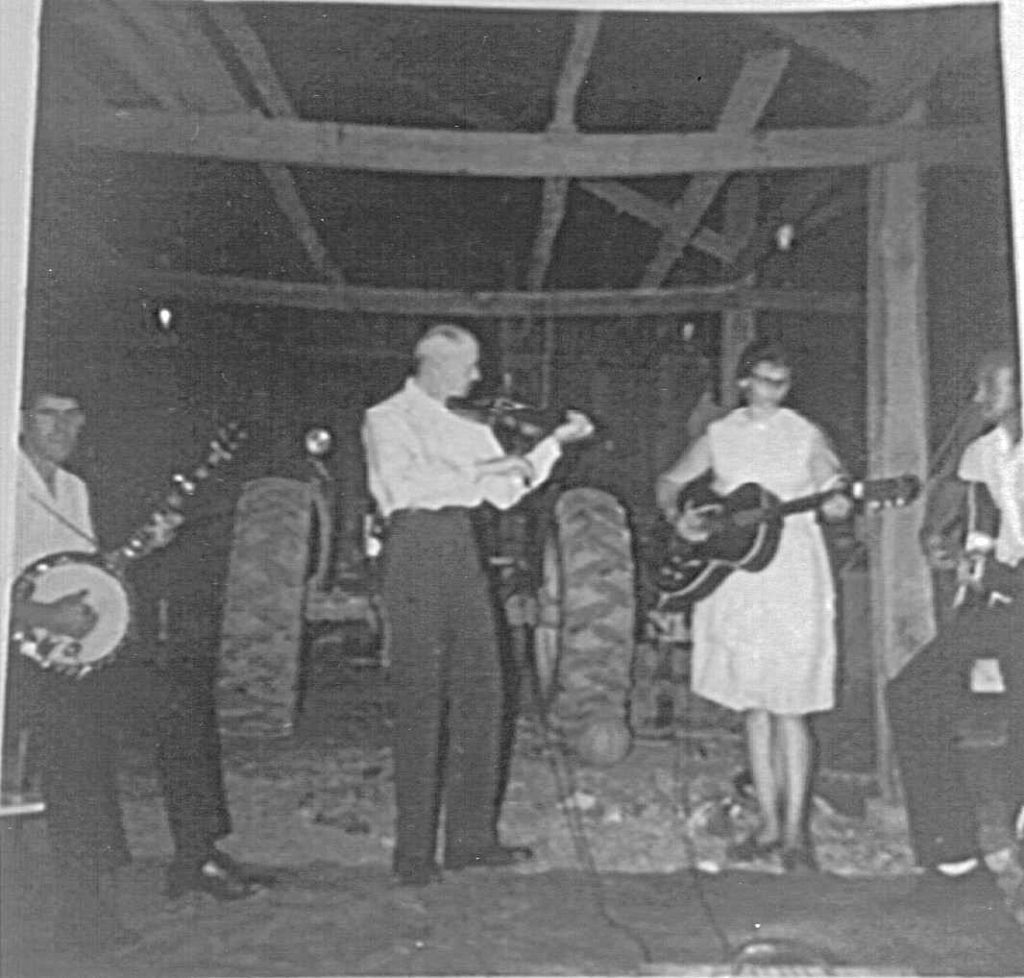

Carlton Rawlings with band (1967), L-R: Arthur Breaze (bjo), Carlton Rawlings (fdl), Loval Black (gtr), unknown (gtr)

Alfred Bailey always spoke with great respect of Carlton Rawlings. The two had played together for many years before Carlton’s untimely death in 1969. By 1986, I had located the four surviving brothers of Carlton Rawlings, as well as his nephew James Rawlings, known to the family as Sonny. Sonny has been most helpful in tracing the family history, finding old photographs, and setting up interviews. The family had preserved 13 reel-to-reel tapes, which included Carlton playing solo and in various combinations with his family and friends. Then not long after my meeting the Rawlings family, Warner Walton gave Alfred Bailey three reel-to-reels of recordings he had made of the Fleming and Bath County fiddlers, with specific instructions to give them to me for preservation. These reels included more of Carlton’s playing. There was of course some deterioration and distortion of sound in the tapes as we received them.

Mark Wilson made the first DAT copies, and Jesse Wells and I worked from those in adjusting levels and minimizing the most glaring distortions. We were conservative in our approach and attempted to leave the rich tones of the fiddle as intact as possible. We believe that the excellence of the playing outweighs any remaining inconsistencies in sound quality.

CARLTON RAWLINGS

Carlton Rawlings was born August 17, 1907 near the little town of Colfax, in Fleming County in northeastern Kentucky, the third child of James and Josephine Barber Rawlings. James, or Jim Tom as he was called, was one of those prominent individuals who filled many roles in the small town communities of rural Kentucky. He was not only a farmer, but also a music teacher and English teacher who taught at the Johnson, Rock Lick, and Arnold’s Chapel schools in southern Fleming County. Later in life he worked as a gauger at a distillery in Frankfort, where his job was to certify the alcohol content of the whiskey. He played both classical and fiddle music on the violin and bought the records of Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifetz. Both Jim Tom and Josephine were known as good singers, and Jim Tom was also good at whistling, a once important musical genre that has not received the attention that it deserves. Asked why with his abundant talent he did not pursue music as a career, he replied that even though he loved music, with nine kids he had to make a living, too. Although Jim Tom could read music, much to the chagrin of Sonny’s mother, he never taught this to the children, and Carlton never had any violin lessons. Although Carlton was purely a traditional fiddler, the exposure to his father’s violin technique as well as to the records Jim Tom kept in the home certainly influenced his left-hand technique and tone production.

Carlton Rawlings was born August 17, 1907 near the little town of Colfax, in Fleming County in northeastern Kentucky, the third child of James and Josephine Barber Rawlings. James, or Jim Tom as he was called, was one of those prominent individuals who filled many roles in the small town communities of rural Kentucky. He was not only a farmer, but also a music teacher and English teacher who taught at the Johnson, Rock Lick, and Arnold’s Chapel schools in southern Fleming County. Later in life he worked as a gauger at a distillery in Frankfort, where his job was to certify the alcohol content of the whiskey. He played both classical and fiddle music on the violin and bought the records of Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifetz. Both Jim Tom and Josephine were known as good singers, and Jim Tom was also good at whistling, a once important musical genre that has not received the attention that it deserves. Asked why with his abundant talent he did not pursue music as a career, he replied that even though he loved music, with nine kids he had to make a living, too. Although Jim Tom could read music, much to the chagrin of Sonny’s mother, he never taught this to the children, and Carlton never had any violin lessons. Although Carlton was purely a traditional fiddler, the exposure to his father’s violin technique as well as to the records Jim Tom kept in the home certainly influenced his left-hand technique and tone production.

Carlton’s grandfather, known as Big Billy Rawlings (b. 1845), was also a good fiddler. Family members recalled him playing such tunes as “Shelving Rock,” “Billy in the Lowground,” and “Snowbird on the Ashbank.” Oren Rawlings remembered Big Billy singing old songs such as “The Cat Came Back” and “The Swapping Song”: “I remember hearing him sitting around the fireplace singing them little old songs to me when I was just a little bitty kid.”

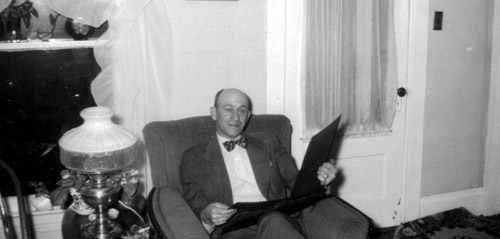

Jim Tom Rawlings family – Pressley, Carlton, Omar, Jim Tom, Madolin, Mabel, Mahala, George, Oren, Charles

A lively musical family and home environment it must have been. Carlton’s three sisters, Mahala, Mabel, and Madolin, all played the piano, and Madolin was the guitar player on some of the recordings. Of the brothers, Oren, George, and Charles played the guitar, and Omar and Pressley played the piano. Oren, the oldest, was a good friend of WLS performer Doc Hopkins and turned down an opportunity for a job on the National Barn Dance because he also had a family to support. A recording session I did with Oren at his home in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky in 1986 revealed him to be a polished and entertaining songster who could certainly have been successful had he chosen a musical career.

Pianos were not unusual in the homes of farming families in this region of Kentucky. The back roads in Bath County today reveal many old abandoned farms with quite substantial dwellings evocative of a time when the rolling hills and valleys supported a relatively prosperous middle class agricultural community. Though not wealthy by today’s standards, such families could nevertheless afford a piano and a house with a parlor to set it in. Sonny reminisced about the importance of the piano in the home:

We moved about every five years. We never lived in a house more than five years when I was growing up. The people that helped us move hated that piano. But Dad (Pressley) would get in there with that little wrench and tune it – he could actually tune the piano. He’d say “That one’s a little off.” He’d do it all by ear. He had no tuning fork or anything else to tell him. Music was their Prozac. That’s how they relaxed. I’ve seen Dad use the piano for Prozac so many times. He’d come in worried about the crop or something and bang on that piano for a while and then come out whistling, ready to go back to work again. He could play “Black Mountain Rag” on the piano.

In 1926, the family moved across the Licking River and settled on the East Fork in Bath County, and Carlton worked on the farm. In 1937, he married Lucille Faris Jones and the couple moved to the county seat of Owingsville where Carlton worked for the Gilmore Construction Company building houses. In 1942, he was drafted into the army and was stationed at Ft. Warren, Wyoming, Prince Rupert, B.C., and Seattle. After attaining the rank of staff sergeant, he was discharged in 1945 and went back to work for the Gilmore Construction Company. In 1951, he took a position with Farmer’s Bank in Owingsville, where he remained until his death in 1969. He was known in the community for his generous and gentle nature. He loved fishing and hunting, but according to Sonny, he was very modest regarding his own abilities with the fiddle.

In 1926, the family moved across the Licking River and settled on the East Fork in Bath County, and Carlton worked on the farm. In 1937, he married Lucille Faris Jones and the couple moved to the county seat of Owingsville where Carlton worked for the Gilmore Construction Company building houses. In 1942, he was drafted into the army and was stationed at Ft. Warren, Wyoming, Prince Rupert, B.C., and Seattle. After attaining the rank of staff sergeant, he was discharged in 1945 and went back to work for the Gilmore Construction Company. In 1951, he took a position with Farmer’s Bank in Owingsville, where he remained until his death in 1969. He was known in the community for his generous and gentle nature. He loved fishing and hunting, but according to Sonny, he was very modest regarding his own abilities with the fiddle.

This brief account of his life, from farmer to small town banker, should remind us of the close-knit social structure that once existed in the rural communities of the outer bluegrass region of Kentucky up until the mid-twentieth century. There was no great degree of separation between farm and town; in the postwar years many young men and women were making a similar transition. I suggested in the introduction to the Rounder anthologies that this settled and stable social structure, based on the relationship between an agricultural community and its small market town, was also a factor in the longer survival of traditions such as singing in the home, fiddling in public, and dancing with friends and neighbors on Saturday night, all of which we found to be more in evidence in this area of the state than anywhere else, at least up until the mid-1980s.

This brief account of his life, from farmer to small town banker, should remind us of the close-knit social structure that once existed in the rural communities of the outer bluegrass region of Kentucky up until the mid-twentieth century. There was no great degree of separation between farm and town; in the postwar years many young men and women were making a similar transition. I suggested in the introduction to the Rounder anthologies that this settled and stable social structure, based on the relationship between an agricultural community and its small market town, was also a factor in the longer survival of traditions such as singing in the home, fiddling in public, and dancing with friends and neighbors on Saturday night, all of which we found to be more in evidence in this area of the state than anywhere else, at least up until the mid-1980s.

Carlton, with Oren backing him up on guitar, frequently played for dances before he was married. After his marriage, Carlton would occasionally play for reunions at the Lions Club Park or street dances in Owingsville, but for the most part he restricted his playing to informal gatherings of family and friends. The Warner Walton recordings seem to have been made in various public settings, such as the family reunions at the park that attracted all the good fiddlers from three or four counties, who would each take their turn on stage to perform throughout a Sunday afternoon. But some of the recordings Sonny had saved were made in Carlton’s utility room, where he kept a reel-to reel tape machine and would record himself playing solo.

While we do not have accurate dates for any of the recordings (though most likely they were made from the late 1950s through the ‘60s), by the time these recordings were made, no doubt times were changing in Bath County as they were everywhere.

It is difficult to accept that such dynamic and sophisticated fiddling representing such a highly developed local tradition – indeed we might say it represents the height of its development – was being produced by a man playing by himself in a room connected to his garage.

His untimely death from a heart attack on September 11, 1969 at the age of 62, before the researchers, aspiring young musicians, and festivals came to the area, certainly deprived us of the opportunity to know someone who would have had an enormous influence on the music revival that was then taking shape across the country. We are indebted to Warner Walton and Sonny Rawlings for preserving these recordings and making them available to family, friends, and students and lovers of traditional music.

HIS STYLE

John Ulery, who played guitar behind Carlton and whose father Raymond played banjo with Carlton on some of the recordings, described what made him unique:

It was mainly his bowing, his phrasing, his tempo, a combination of all that. He was a good musician. Every fiddler, the bowing is a little unique. If you’re familiar with them, it’s easy to recognize a fiddler by their bowing and how they phrase things. And Carlton, he was different than the others. His tempo was a little fast, faster than most of the fiddlers. I feel lucky to have played with Hawkins and Rawlings. They were the best.

Besides his father, the main influence on Carlton’s playing was Tom Riley, whose name was legendary in Fleming and Bath Counties. Riley’s parents had emigrated from Ireland and settled near Sherburne on the Licking River sometime in the late 1800s. Tom and his brother Steve were both good fiddlers, but Tom Riley’s influence was predominant on the next generation of fiddlers in the area. His Irish heritage of hornpipes, jigs, and reels in minor keys, combined with the unusual kind of syncopation employed by the Kentucky fiddlers of this area, produced a distinctive style among the fiddlers of Fleming and Bath County. Oren Rawlings described Tom Riley and his influence on Carlton:

He was a great old-time fiddler. I’ve seen him play, and he had a style all his own. He never did sit down to play, he’d stand up just as straight, and Carlton learned that from him – he did all his fiddling standing up. He had a wide variety of tunes. He played a lot of hornpipes, jigs, and reels besides the regular old country fiddle tunes like “Martha Campbell. ” He had a wide repertoire, and he knew what to do with that fiddle and bow. And he had the tone – that’s where Carlton got his. He was a stylish fiddler. Carlton patterned his styling after Tom Riley. His arm was as limber as a rag from his shoulder down.

Tom Riley in later years moved north to Marion, Indiana, but made visits back to Kentucky to stage fiddle contests and see old friends. On some of these visits he was accompanied by John Summers, the great fiddler whom Riley had met when he moved to Marion. John Summers is the fiddler whose playing Carlton’s most closely resembles, and it is evident that both were strongly influenced by Tom Riley. After many years of listening to old-timers talk about Tom Riley, miraculously I found a disc of his playing. Both tunes from this disc will be included in the next volume of home recordings to be issued in this series.

Tom Riley in later years moved north to Marion, Indiana, but made visits back to Kentucky to stage fiddle contests and see old friends. On some of these visits he was accompanied by John Summers, the great fiddler whom Riley had met when he moved to Marion. John Summers is the fiddler whose playing Carlton’s most closely resembles, and it is evident that both were strongly influenced by Tom Riley. After many years of listening to old-timers talk about Tom Riley, miraculously I found a disc of his playing. Both tunes from this disc will be included in the next volume of home recordings to be issued in this series.

The recordings show Carlton adjusting his approach to playing at different tempos. In the ensemble settings, he seems to have played mostly standard tunes in a relatively straightforward manner, but in the solo recordings we can hear all the stylistic devices of the local style on full display. Most of the notes are bowed with single saw strokes, but these strokes are syncopated in complex string-crossing patterns. Slurs are used sparingly but effectively to set up these syncopated patterns. Further ornamentation is achieved with finger and bow trills, triplets, slides, and slightly flattened microtones. Even with such dazzling technique, his playing is spontaneous, not technical. The techniques are employed in the service of a feeling and a passion that is often right on the edge. The many variations he achieves in the more moderate tempos, combined with the drive and intensity he displays at the faster tempos, certainly place him in the highest rank of traditional fiddlers.

The recordings show Carlton adjusting his approach to playing at different tempos. In the ensemble settings, he seems to have played mostly standard tunes in a relatively straightforward manner, but in the solo recordings we can hear all the stylistic devices of the local style on full display. Most of the notes are bowed with single saw strokes, but these strokes are syncopated in complex string-crossing patterns. Slurs are used sparingly but effectively to set up these syncopated patterns. Further ornamentation is achieved with finger and bow trills, triplets, slides, and slightly flattened microtones. Even with such dazzling technique, his playing is spontaneous, not technical. The techniques are employed in the service of a feeling and a passion that is often right on the edge. The many variations he achieves in the more moderate tempos, combined with the drive and intensity he displays at the faster tempos, certainly place him in the highest rank of traditional fiddlers.

THE TUNES

The keys indicated for the tunes are the keys for the fingering. Variations in tape speed combined with inconsistencies in the pitch to which the fiddle was tuned may still leave us with some questions, but all tunes are played in standard tuning, however higher or lower in absolute pitch. Neither was it possible to identify the accompanying musicians for each track but the following names appear on the tape boxes: Warner Walton and Johnny Ulery, guitars; Raymond Ulery and Arthur Breaze, banjos. Sonny identified Carlton’s sister Mahala as the piano player. As previously mentioned, we also know that his brothers Oren, George, and Charles provided guitar on some of the sessions.

- Snowbird on the Ashbank (G) – This was the floating title the Rawlings fiddlers gave to the venerable tune otherwise known in Kentucky as “Wild Horse,” or “Buck Creek Girls.” The tune has Irish and Scottish antecedents, but its earliest American incarnation under the title “Stony Point” commemorates Mad Anthony Wayne’s successful capture of the British fort at Stony Point, New York in 1779. Rowan County fiddler J. W. Day called it “The Wild Horse of Stony Point.”

- Grand Hornpipe (D) – This was the name used in the northeastern corner of the state for the tune more often known as “Rocky Mountain Goat.”

- Flowers of Edinburg (G) – This was another tune played by Tom Riley. It first appears in James Oswald’s Curious Collection of Scots Tunes (II), published in 1742. On some of the Riley tunes such as this one, we can hear Carlton capturing the tone colorings of his mentor.

- Soldier’s Joy (D)– Probably the best-known fiddle tune of all time, this tune occurs in every fiddle tradition in Europe and North America. Even so, a fiddler like Carlton Rawlings provides a definitive rendition and gives new life to a tune that everyone has heard countless times. The heavy rhythmic bowing on this piece was typical of the area and brings to mind the square dance style of Bob Prater from nearby Foxport in Lewis County.

- Miller’s Reel (A) – A number of the Tom Riley tunes are found in printed collections, this one appearing in Cole’s 1000 Fiddle Tunes. Kerry Blech supplied some background: In Cole’s, the tune is attributed to Zeke Backus, a minstrel show fiddler who was a contemporary of Daniel Decatur Emmett. An earlier antecedent is “The 22nd of February” in Knauff’s Virginia Reels (1839). Several informants told us that Riley could read music. The relatively large number of book tunes in the repertoire of an area where musical literacy was not common suggests that fiddlers who could not read music would often learn tunes from those who could. George Hawkins and J. P. Fraley, both from the same area of the state, played a variant of “Miller’s Reel” in the key of G.

- Old Time Twinkle Little Star (G) – The well-known tune played by Howdy Forrester, Paul Warren, and Kenny Baker was once played as a schottische, and that was how it was played by older fiddlers in Kentucky, including Carlton. It derives from a 19th century popular song composed by Fred MacEvoy in 1879, but it survived as a fiddle tune long after its song origins had been forgotten and eventually morphed into the showy breakdown that was popular among bluegrass fiddlers in the 1950s and ‘60s.

- Leather Britches (G) – This difficult but popular American fiddle tune is descended from the Scottish tune “Lord MacDonald’s Reel.” The American title probably refers to green beans that were strung up to dry with needle and thread. The strings of beans were called “leather britches.” A more fully elaborated setting of this tune could not be imagined. The characteristic Kentucky syncopated string crossings, the variations, trills, triplets, and slides show a master fiddler at his best.

- Wagoner (C) – Gus found a reference that might explain the origins of two fiddle tune names. In a horse race held in Louisville, Kentucky on September 30, 1839, Wagner, a blaze-faced chestnut from Tennessee, defeated the Kentucky champion Grey Eagle by a nose. The Kentuckians, in their vainglory, demanded a rematch after so close a defeat. The rematch was held within the week, and Grey Eagle was ridden so hard that he broke down before the finish, giving Wagner an easy victory. The tune derives from “The Belle of Claremont Hornpipe” and remains one of the most popular American fiddle tunes. It can claim a special distinction in our cultural history: it was supposedly the first tune that Uncle Jimmy Thompson played in his debut on Nashville’s WSM in 1923, the broadcast that is recognized as the beginning of the Grand Ole Opry.

- Katy Hill (G) – Popularized by the recordings of Arthur Smith and Bill Monroe, this tune became a standard of Grand Old Opry hoedown fiddlers who, Mark Wilson believes, simplified the melody to facilitate a faster tempo that was more about showmanship than danceability. Carlton’s version, played solo at a moderate tempo, reflects an older approach, entirely in the language of the Fleming-Bath County style. Popular tunes, sometimes over-worked to the point of cliché, can become interesting and compelling again in the hands of a traditional player at home in his own idiom.

- Arthur Berry (D) – This was a Tom Riley tune that was a favorite of George Hawkins and Alfred Bailey. John Summers, in an interview with Joel and Kathy Shimberg, provided the background to the tune. A fight broke out at a dance and someone shouted for the fiddler to start playing a tune to quiet the crowd. The fiddler, not knowing what he was playing, started playing this tune and the fighting stopped, but not before a man named Arthur Berry was killed, and so the tune was named after him. It is a variant of the tune played in Lewis County as “The Yellow Barber.”

- Martha Campbell (D) – The tune most commonly associated with Kentucky fiddling allows for endless variations in rhythm and phrasing that define each player’s setting as uniquely their own. This is certainly the most notey “Martha Campbell” ever recorded, but the rhythm and drive are not sacrificed. A stunning duet of Carlton and Alfred Bailey playing this tune will be included in the next volume of these home recordings.

- Sally Goodin (A) – Carlton plays this tune as it was played by Kentucky fiddlers, unlike the modern versions that derived from Eck Robertson’s 1922 recording that spread and took root across the country. Bruce Greene recounted a story that gives the tune a Kentucky connection. Supposedly there was a Sally Goodin who ran a boarding house on the Big Sandy River that was frequented by Confederate soldiers during the Civil War, and they re-named the tune, which was originally called “Boatin’ Up Sandy,” after her.

- Waynesboro (G) – This tune was well known among older fiddlers in central and eastern Kentucky. Doc Roberts, who recorded the best-known version, learned it from the black fiddler Owen Walker (b. 1854). Wolfe County fiddler Darley Fulks (b. 1895) learned the tune from his grandfather, who called it “Andrew Jackson.” “Waynesboro” does have an Irish ancestor (“Over the Hill to Maggie”), and Carlton’s setting, which is different from other Kentucky versions in its high strain, may therefore have come from Tom Riley.

- Mississippi Sawyer (D) – This standard tune dates from the early 19th century and was played all through the South. A “sawyer” was a snag or submerged tree trunk that was a danger to steamboats.

- Humphrey’s Jig (G) – This difficult tune, which seems to have survived in northeastern Kentucky and nowhere else, as Mark and Gus pointed out, is derived from the Scottish “Bob of Fettercairn” and the Shetland “Knack and Knockit Corn.” Though most of our sources probably learned the tune from Tom Riley, Alfred Bailey said that Tom York, the father of Bath County fiddler Henry York, had learned the tune from a man named Hiram Humphries. Oren Rawlings had some vivid memories of Hiram Humphries:

He was a Fleming County man. He was born and raised up around Muses Mill. He spent many years of his life, half of it in Kentucky and half of it in Florida. He was a great fisherman and a great fiddler. He used to sell glasses. He fitted glasses, and he could fit them pretty good. That was back when they’d carry a little case full of glasses, and whichever one got the job done, that’s what people would buy, them little steel rim glasses. He would go to Florida and stay down there and kill alligators and fish. He never married ‘til way up late in life. He could build an air rifle that could shoot through an inch beech board, seasoned beech. He was a crackerjack fiddler, and he could read music enough to learn nearly anything he wanted to learn. He and my dad could learn it that way. But “Humphrey’s Jig” was Tom Riley’s piece.

So regardless of who first brought the tune to the area and spread it to the local fiddlers, it is possible that this Hiram Humphries was the man whose name became attached to the tune.

- Brickyard Joe (G) – This tune, usually associated with Doc Roberts, was known throughout central Kentucky by fiddlers who had never heard of Doc Roberts. Carlton’s setting, substantially different from Roberts’, must have been learned locally.

- Chicken Reel (D) – Ever popular among country fiddlers, “Chicken Reel” is more than sound effects. Played cleanly as a medium tempo breakdown, it can be challenging to the fiddler and exciting to dancers.

- Shortnin’ Bread (G) – The simplistic little ditty known throughout the South becomes a tour de force in Carlton’s hands.

- Greek Melody (G minor) – This was a Tom Riley tune of Irish origin that was also played by George Hawkins and Alfred Bailey. Tom Riley’s playing of this tune will be included on the next volume in this series.

- Gray Eagle (A) – Although there are other tunes by this name in the repertoires of source fiddlers across the upper south, this is the standard Gray Eagle in A that was played by older fiddlers in Kentucky, suggesting that the A tune also has roots in the 19th century. The 1839 horse race cited above may explain the name, but Gray Eagle was also the name of a packet on the Ohio River at the time of the Civil War. The piano accompaniment by Carlton’s sister Mahala on this recording and on Track 21 (“Ragtime Annie”) was fairly typical of the sound we often heard in northeastern Kentucky. George Hawkins also was recorded by Gus and Mark with his daughter on piano.

- Ragtime Annie (D) – Gus noted that this tune, known all over the United States and Canada, does not appear in early printed collections and most likely dates from around the turn of the 20th century. Its earliest appearance is the 1922 recording by Texas fiddler Eck Robertson.

- Whistlin’ Rufus (G) – This tune was composed in 1899 at the beginning of the ragtime era by Kerry Mills, who was also the composer of “Red Wing.” Early recording artist Asa Martin sang the original song about a black guitar player from Alabama who played solo for cakewalks with just his guitar and his whistling. Known all over the South, it is recast by Carlton into a showpiece of the Fleming-Bath County style.

- Billy in the Lowground (C) – We can hear the Irish inflection coming through in the plaintive bending of the notes and the subtle trills. While we do not have a recording of Tom Riley playing this tune, based on a close listening to his playing on the recordings we do have, this must be Tom Riley’s setting of the tune.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS [from the original 2012 release of this CD]

This project owes its inception to James “Sonny” Rawlings, It could not have come about without his knowledge and perseverance, his long and faithful devotion to the Rawlings family legacy, and his knowledge of Bath County history. Sonny, like his grandfather Jim Tom (and the Rawlings in general), is a jack-of-all trades as well as an engaging raconteur. His life and interests are interwoven with the fabric of Bath County. It has been an education and one of the rewarding experiences of my life to know and work with him.

Unless otherwise noted, the tune histories come from Andrew Kuntz’s The Fiddlers Companion: A Descriptive Index of North American, British Isles, and Irish Music for the Folk Violin and Other Instruments (www.ibiblio.org/fiddlers).

Others we would like to acknowledge for their support and encouragement: the late Alfred Bailey, Warner Walton, and John Ulery; Mark Wilson, Raymond McLain, Nathan Kiser, The Kentucky Center for Traditional Music, Don and Carmen Rogers, John Gallagher, Jamie Wells, Scott Prouty, Andy Fitzgibbon, Kerry Blech, John Schwab, and of course, as always, our wives, Tona Barkley and Amanda Lynn Wells.

CREDITS

Produced by John Harrod and Jesse Wells

Digital transfers by Mark Wilson

Remastered and edited by Jesse Wells

Notes by John Harrod

Jacket design by Toni Hobbs