The Lost Recordings of Banjo Bill Cornett (FRC304)

by John Cohen

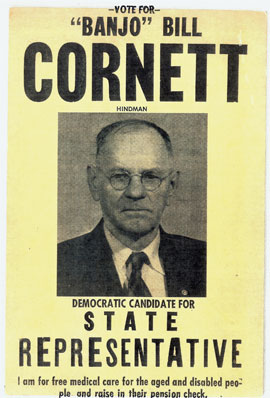

Bill Cornett was born in East Kentucky in 1890. He started playing banjo at age eight. His musical flair, he reported, was inherited from his mother who sang ballads to him. He operated a country store two miles outside of Hindman. It is said that he’d rather sit and pick his banjo than wait on customers. In 1956 he was elected to the Kentucky State Legislature, representing Knot and Magoffin counties. A Democrat, he picked and sang his way to his first term. “You know how I win? I get the young folks with my music and the old-folks by fighting for old age benefits.” He was proud of his composition “The Old Age Pension Blues,” which he sang on the floor of the Legislature. While serving in the House of Representatives in Frankfort, at age 69 he died of a heart attack while picking his banjo to entertain the customers at a downtown restaurant. The following day, his banjo was banked with flowers at his desk in the House chamber at the Capitol.

I first met him in 1959 at his home near Hindman. Some officials from the United Mine Workers had brought me to his house to hear his music. I was in Kentucky to document local music, and Bill was the first person I recorded. Although he was reticent about performing for my tape recorder, he respected the UMW men’s request and for about an hour, Bill played and sang a bunch of songs, which I recorded and eventually issued on Folkways “Mountain Music of Kentucky.” He would often announce during the song that he was the performer and the composer of the music. He claimed that some of his original songs had been taken from him and plagiarized. He was wary of folksong collectors. He also told me that he had already recorded his best material – it was inside on his tape recorder.

Banjo Bill Cornett died before “Mountain Music of Kentucky” came out, and for many years I asked his family if I might hear Bill’s own recordings. I tried several times during the first ten years, and then gave up. In 1995 I visited the Hindman Settlement School, and asked about memories of Bill Cornett. In 2002, forty three years after my initial recordings, I heard from Bill’s son Brode Cornett who told me that he had listened to the tapes, and heard his father’s voice say that he wanted his music to be heard. The original quarter inch tapes had been destroyed, but eventually Brode sent me his own cassette copies of the tapes. That is how these recordings came to light, so many years after they were recorded.

Although the sound quality of the cassette copies was worn and torn, the music was excellent…Bill was a great singer and a powerful banjo player. He was of a generation 20 years earlier than Roscoe Holcomb, and his music offered some special insights into Eastern Kentucky music. He had his own ideas about phrasing, used many different banjo tunings, and had the odd practice of repeating a section of the melody on the banjo right after he sung it. He had a variety of picking styles, from the old frailing approach to picking lead notes with his fingers, or playing lead with his thumb in conjunction with strumming the strings…something akin to the Carter family approach to guitar. He also created an African sound (like a griot approach) on the banjo, which accommodated a few of his blues-like songs (“Lonesome Road,” “Hustling Gamblers,” and “Old Ruben.” Throughout all his banjo playing, Banjo Bill created a way to retain the extended, idiosyncratic phrasing of his singing.

It is reported that he met Uncle Dave Macon at the Grand Ole Opry, and that he got his banjo from him. It was a Bacon Belmont, with hand carved ivory on the neck and tuning pegs. John Hartford & myself both remembered that Bill’s banjo bridge was plastic, a bright fluorescent pink.

In the 1950s his son Brode had loaned him a reel-to-reel tape recorder which he had obtained while serving in Germany. As Bill put it, at this time his children were into “honky-tonk and rock and roll,” so he would play his banjo while they were out, and that was when these recordings were made.

Bill Cornett had been a public figure in his home locale. During the depression of the 1930’s he was known as someone who would supply food to the needy: he’d bring lunch boxes and bags of beans to people on relief, as part of the WPA program, where he was a boss/ administrator. He also ran a local country store that sold furniture and supplies. Local people would come listen to his music; old people would cry at his lonesome songs, others would dance to his banjo.

His wife had been a weaver at the nearby Hindman School and kept traditional patterns alive.c She had been a student at the school when it first opened, and had memories of waiting on school founders who came from Massachusetts.

When he won his seat in the Kentucky State Legislature, Bill Cornett was already so well known locally that he never campaigned for office, and he won the election with 83% of the vote. He composed a song called “The Old Age Pension Blues,” and sang it on the floor of the Kentucky Legislature, accompanied by his banjo (the song can be heard on “Mountain Music of Kentucky,” on Folkways). When he died, the Governor of Kentucky tried to persuade his son Brode to fill his father’s seat in the Legislature. There were many articles about his funeral in the local papers (which provided much of the history presented here).

His nephew Otis Cornett recalls that Bill listened and learned songs from Victrola records. In 1956 he performed in St. Louis at the National Folk Festival (and brought home a prize); John Hartford remembered seeing him there. It was also reported that he played at Getrude Knott’s Festival in Floyd County, at Jenny Wilder State Park. Jean Ritchie had made some recordings of him in the 1950s. She was particularly impressed by his version of “I Ain’t Gonna Work Tomorrow” which contained many verses with which she was unfamiliar. When I recorded him, Bill told me that Pete Seeger had sat at his feet and learned banjo playing from him. Pete remembers hearing him in Kentucky.

The wild vigor of his singing, coupled with the intricate busy-ness of his banjo – full of rapid dropped thumb and pull offs – produced a distinctive sound, in which the melody appears slow and drawn out, in a lyrical way that contrasts with the rhythmic, percussive banjo sound. Other East Kentucky musicians share this approach, but with Bill Cornett it was most pronounced. I recall from my brief time with him that his banjo was sometimes tuned low, which afforded him an easier time bending and slurring specific notes (getting the sound of a fretless banjo), to echo the blues-like quality of his singing.

One is tempted to compare his music to the 1939 Alan Lomax recordings of Justice Begley (who was the sheriff of Hazard), to hear similarities in the relationship of vocal and banjo styles. Bill Cornett’s repertoire ranged from old ballads to mountains songs, banjo tunes, sentimental and patriotic tales. Some contain elements of Broadside ballads, and some reflect a nineteenth century Irish lyric.

His music adds another facet to the extraordinary range of banjo playing and mountain style singing that emanated from East Kentucky. He joins the pantheon of Buell Kazee, B.F. Shelton, Roscoe Holcomb, Morgan Sexton, Hayes Shepherd, Pete Steele and Walter Williams.

Thanks to

Mike Mullins at the Hindman School

Otis Cornett

Brode Cornett

Pete Reiniger at Smithsonian Folkways for the transfers

Jean Ritchie for her memories

Discography

Banjo Bill Cornett appears on “Mountain Music of Kentucky,” and “Back Roads to Cold Mountain,” both on Smithsonian Folkways. For great contextual listening, listen to “Kentucky Mountain Music,” Yazoo 2200.